The damage the corona virus has wrought in the cultural world is beyond imagining. There is no way to classify or quantify the losses, ones that will be felt for decades, maybe even centuries, to come. Galleries, museums, studios, open spaces, cinemas, opera houses and concert halls are shuttered, with long-planned, eagerly anticipated events and seasons cancelled; one agency has shut down so far. The harsh realities of the force majeure clause contained in many contracts echo through every vast, empty space where people should be. The global pandemic has laid bare the extreme fragility of arts organizations and those who depend on them.

Along with extensive virtual tours, online streaming has, over roughly the past two weeks, become a way of keeping the cultural flames alive. The charming nature of many of the broadcasts affords a peek into the home life of artists, places which are, in normal times, rarely seen by many of the artists themselves. The livestreams also provide a reassuring familiarity, a reminder that the tired, anxious faces are exact mirrors of your own tired, anxious self. Artists: they’re just like us. In better times it is sometimes easy (too easy) to be fooled by the loud cheers, the five-star reviews, the breathless worship, even when we think we may know better. What’s left when there’s no audience? These videos are providing answers and some degree of comfort. It’s heartening to see Sir Antonio Pappano sitting at his very own piano, his eyes tender, his voice and halting words reflecting the shock and sadness of the times. Moments like these are so real, so human, and so needed. They are a panacea to the soul. The arts, for anyone who needs to hear it, is for everyone, anyone, for all times but especially for these times. Pappano’s genuine warmth offers a soft and reassuring embrace against harsh uncertainty.

Equally as buoying have been the multiple together-yet-apart performances by numerous orchestras, including Bamberger Symphoniker’s recent presentation of a section of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s performance of Copeland’s Appalachian Spring. There are so many examples of this type of fellowship which have sprung up, and they are all worth watching. One of my personal favourites is a solo performance from violist Marco Misciagna, who is currently volunteering with the military corps of the Italian Red Cross (CRI). Misciagna performs outside the Southern Mobilization Centre, mask firmly in place, leaning into tonalities and, one can almost hear, breathing in and through his instrument’s strings. As an opinion piece in The Guardian noted, “When people look back on the pandemic of 2020, they will remember many things. One of them ought to be the speed with which human beings, their freedom to associate constrained, turned towards music in what may almost be described as a global prisoners’ chorus.”

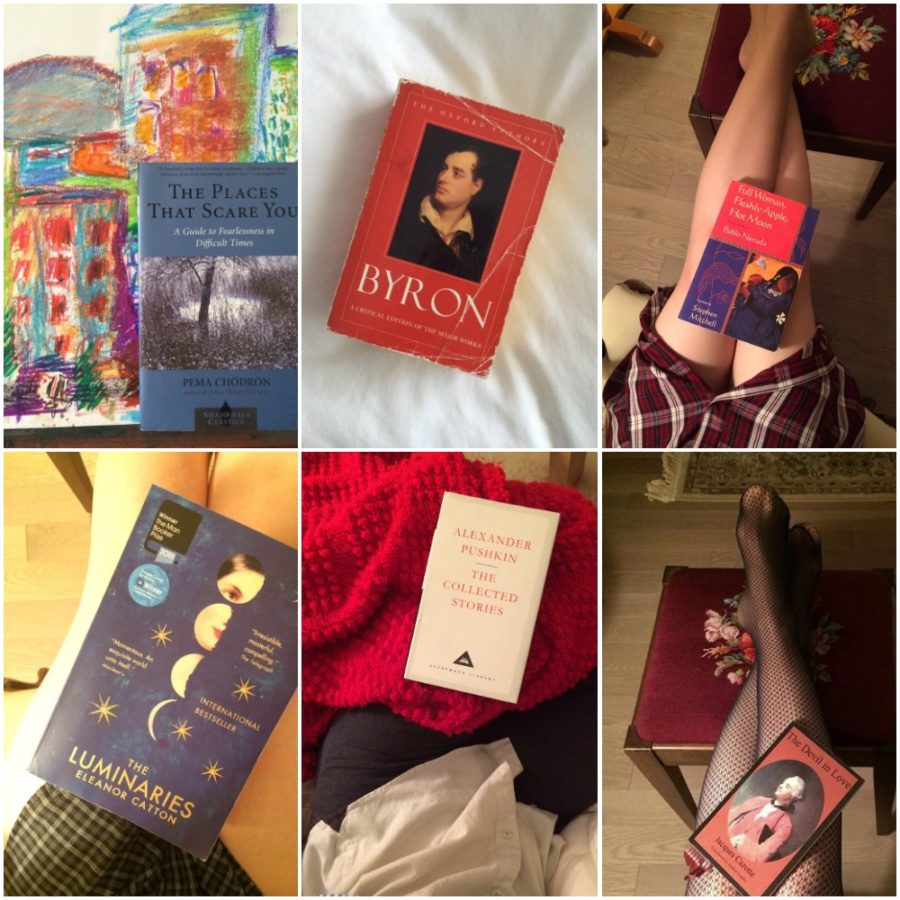

Some may also perceive the recent flurry of online activity as savvy marketing, and there’s little wrong with that; they — we (if I can say that) — need every bit of arm-waving possible. Performing for a captive audience in need of inspiration, hope, distraction, diversion, and entertainment fulfill a deep-seated need for community. Choosing where and how to direct our attention, as audience members, is no easy thing (although, to be frank, my own efforts to filter out the hard-posing ingenue/influencer types have become increasingly more concentrated). To be faced with such a sweet and succulent buffet whilst facing the sometimes sour and glum realities of ever-worsening news is no small thing. Shall it be a weekly livestream from Bayerische Staatsoper or one of Waldemar Januszczak’s wonderful art documentaries? Perhaps a modern opera work from the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre, or a Jessica Duchen reading her great novel Ghost Variations? Maybe a dip into the Berlin Philharmonic’s vast online archive or piano sounds with Boris Giltburg and then Igor Levit? Perhaps it’s time to mop the floor and clean out the humidifiers? Maybe time to tackle that terribly overdue filing? Shall I check Twitter yet again for the latest? Dare I dip into Facebook? is it time to update both groups of students? What words of comfort and encouragement should I choose as their teacher/mentor? Is it time to check in with my many lovely senior contacts – maybe a phone call? When the hell am I going to finish (/start) that immense novel that’s been sitting on the table acting as a defacto placemat?! Cultural options (physical media collection included) have to compete with less-than-glamorous ones, but, orchestrated in careful harmony, work to keep one’s mental, emotional, and spiritual selves humming along, and offer a reminder that the myth of individualized isolation is just that – a myth.

Sir Simon Rattle conducts the Berlin Philharmonic in a program of music by Bartók and Berio on March 12, 2020. The Philharmonie Berlin is closed until April 19th but the orchestra is offering free access to online archives at its Digital Concert Hall. Photo © Stephan Rabold

Professional duties remind us of the fallacy of isolation, underscoring them with various technological notifications in bleep-bloop polyphony. Obligation can’t (and doesn’t) stop amidst pandemic, especially for those in the freelance world. Writers, like all artists working in and around the arts ecosystem, are finding themselves grappling with a sickly mixture of restlessness and terror as the fang-lined jaws of financial ruin grow ever-wider. Since January I’ve been part of a mentoring program run through the Canadian Opera Company (COC) and Opera Canada magazine. This scheme, a partnership with a variety of Toronto-based arts organizations, allows emerging arts writers currently enrolled in journalism school the opportunity to see and review opera. Along with opera, students also write about productions at the National Ballet of Canada, concerts at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, presentations at Soulpepper Theatre Company. Some indeed come with theatre and dance backgrounds (or equivalencies in written coverage), a great help when covering the sprawling, integrative art form that is opera. For many, this isn’t merely a first outing in writing about the art form; it’s their very first opera experience, period. Next up (we hope) are the COC’s spring productions of Die fliegende Holländer and Aida. Lately I’ve been crossing fingers and toes at their arts (and arts writing) passion continuing; each writer I have mentored thus far has possessed very individual talents and voices. I am praying they, and their colleagues, are using at least some of these stressful days to exercise cultural curiosity and gain as much richness of exposure as the online world now affords. It’s not purely practical; surely on some level it is also medicinal.

Soprano Hanna-Elisabeth Müller and baritoneMichael Nagy rehearse ahead of their March 23, 2020 performance at Bayerische Staatsoper as part of the house’s weekly Monday broadcast series. Photo: Wilfried Hösl

What happens to those voices now, of writers new and old? What happens to their potential readers, to audiences, to new fans, to old fans? Will they (we) get an opportunity to be part of the ecosystem? Will there even be one left to write about? Similar anxieties have surfaced for my radio documentary students. Tell your own stories! I constantly advise, This is a writing class with sound elements! When today’s first online class drew to a close, it seemed clear no one wanted to leave; there was something so reassuring about being able to see (most) everyone’s faces, hear their voices, share stories, anxieties, fears. I have to agree with historian Mary Beard’s assessment in The Times today, that “I am all in favour of exploiting online resources in teaching, but no one is going to tell me that face-to-face teaching has no advantage over the remote version. Lecturing and teaching is made special by real-time interaction.” Sharing stories is more crucial than ever, whether through words, music, or body, or a skillful combination of them all. As director Kiril Serebrennikov (who knows a thing or two about isolation) wisely advises, keep a diary. I started doing just that recently, reasoning that writing (like sound and movement) is elemental to my human makeup ; whether or not anyone reads it doesn’t matter. Exercises in narcissism seem pointless and energetically wasteful, now more than ever. The act of writing – drawing, painting, cooking, baking (all things I do, more than ever) – allow an experience, however tangential, of community, that thing we all need and crave so much right now. We’re all in the same boat, as Pappano’s expression so poignantly expressed. It’s something many artists and organizations understand well; community is foundational to their being.

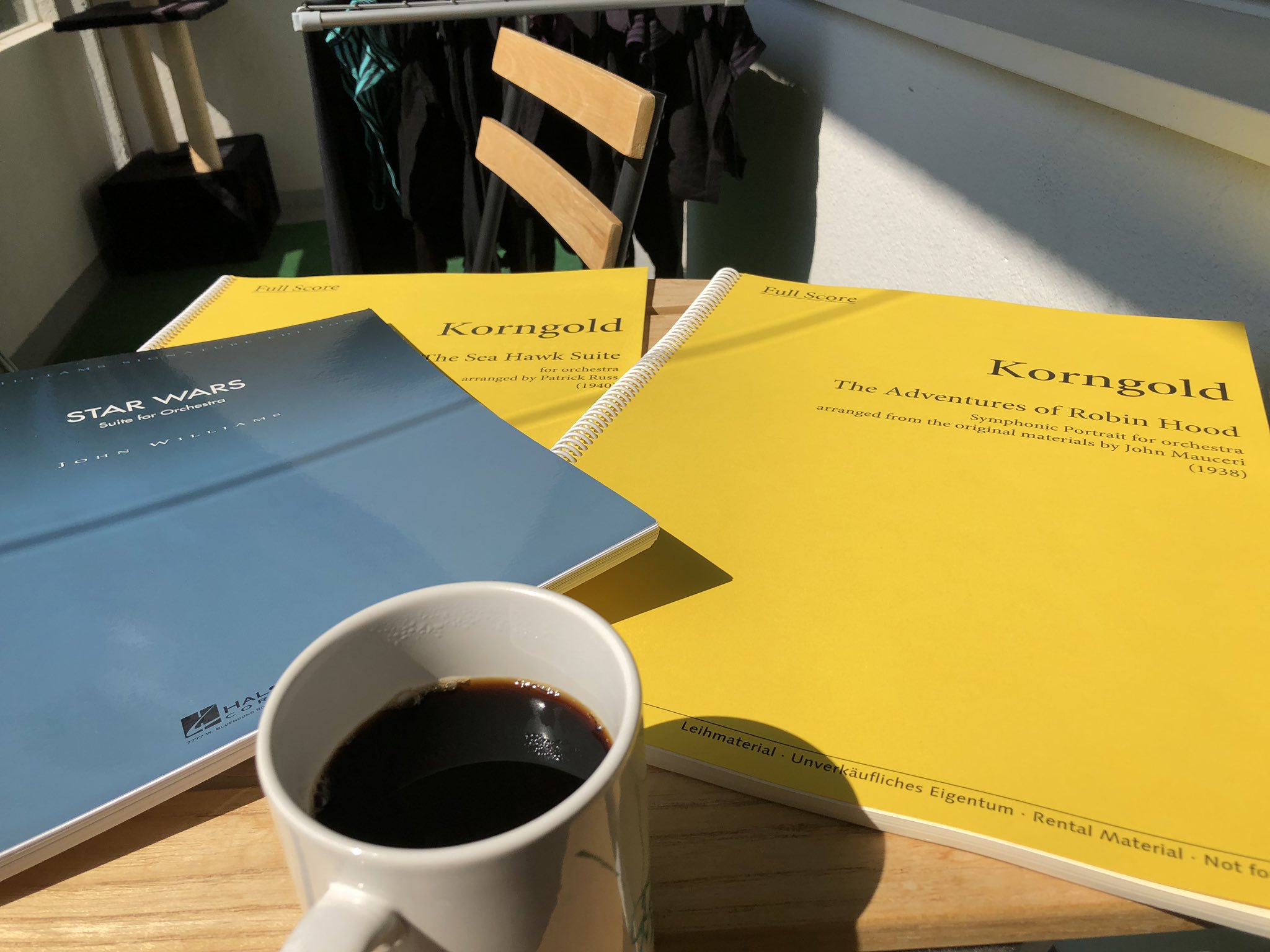

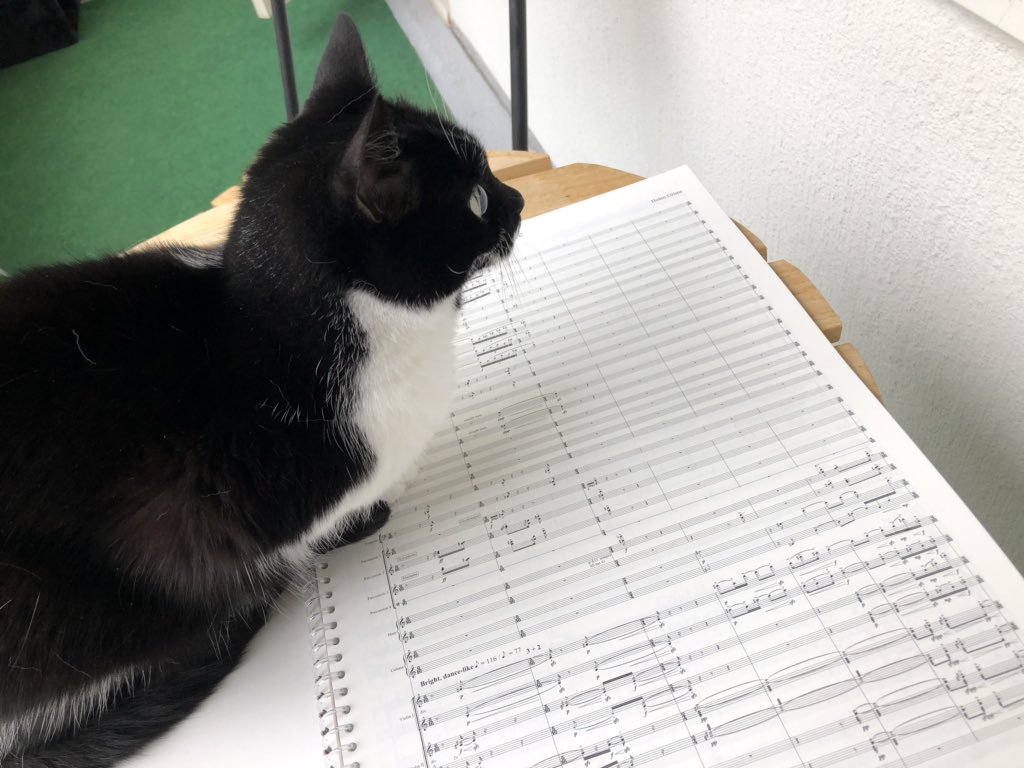

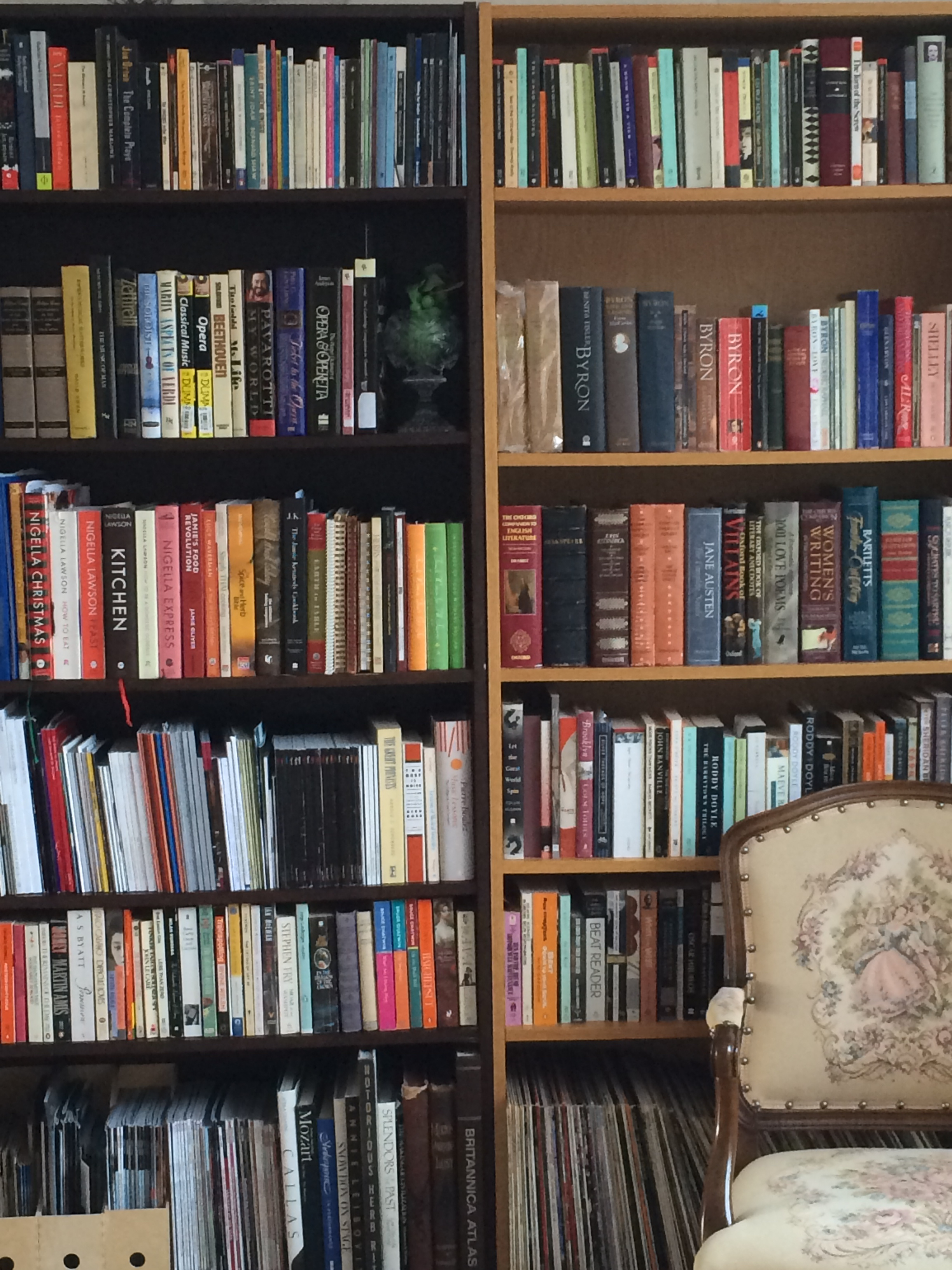

Photo: mine. Please do not use without permission.

The ever-changing waves of my own freelance life are largely made up of the elements of writing and sound, with community and isolation being their alternating sun and moon. Quarantine means facing the uncomfortable aspects of ourselves: our choices, our behaviours, our treatment of others, our home lives, our approach to our art, and how we have been fitting (or not) these multiple worlds together. Noting the particularly inspiring German response around support for freelancers has made my continentally-divided self all the more conscious of divisions within perceptions of the value and role of culture, but it’s also forced some overdue considerations of just where a writer working so plainly between worlds might fit. Maybe it is naive and arrogant to be questioning these things at such a time in history, and publicly at that – yet many artists seem to be doing similar, if social media is anything to go on. There seems to be a veritable waterfall of honesty lately, with rivulets shaded around questions of sustainability, feasibility, identity, and authenticity, just where and how and why these things can and might (or cannot, now) spiral and spin around in viscous unity. I shrink from the title of “journalist” (I don’t consider myself one, at least not in the strictest sense), but whence the alternatives? One can’t live in the world of negative space, of “I am not”s (there is no sense trying to pitch a flag in a black hole), nor derive any sense of comfort in such non-labelled ideas, much as current conditions seem to demand as much. (The “I will not go out; I will not socialize” needs to be replaced with, “I will stay in; I will be content,” methinks.) Now there is only the promise of stability through habits new and old, and on this one must attempt nourishment. The desire to learn is ever-expanding, like warm dough in a dimly-lit oven, eventually inching beyond the tidy rim of the bowl, into a whole new space of experience, familiar and yet not.

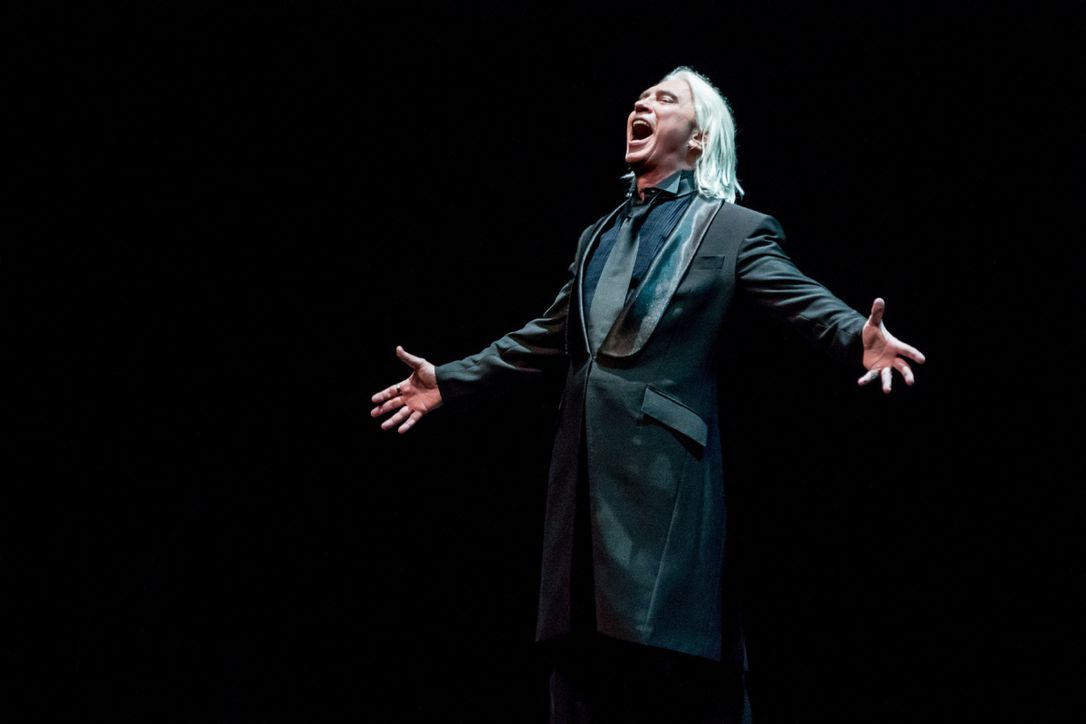

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Where is the place, I wonder, as fists pound and knuckles grind and the dough that will eventually be loaves of oatmeal molasses bread squeaks and sighs, where is the place for writers in this vast arts ecosystem that is now being so violently clearcut? What will be left? The immediate heat of the oven feels oddly reassuring as I ask myself such things, a warmth that brushes eyelashes and brings to mind the wall of strings in the fourth movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. We are all being forced into a new structure, and we cannot ask why. There is only the experience of the present, something the best art has, and will always embrace, express, and ask of us. As Buddhist nun and author Pema Chödrön writes:

All of us derive security and comfort from the imaginary world of memories and fantasies and plans. We really don’t want to stay with the nakedness of our present experience. It goes against the grain to stay present. There are the times when only gentleness and a sense of humor can give us the strength to settle down.

The pith instruction is, Stay. . . stay. . . just stay.

What is there now but the present? I think of the many artists so affected at this time, and I thank them all; their authenticity, courage, and commitment to their craft are more needed and appreciate than can be fathomed. There is a place for them; it is here, it is now, and it is our community, a grand joining of sound and soul and presence. Let’s tune in, together.