In 2003, at the very the beginning of the Second Iraq War, my mother and I had gone out for a meal and when we came home, she poured us glasses of whiskey, and put on an old recording of Verdi’s Don Carlo. (The 1983 Metropolitan Opera production featuring Placido Domingo and Mirella Freni, to be precise.) I don’t remember what was said in turning it on, but I remember the look on her face after the First Act. “We’re going to wake up tomorrow and a bunch of people we don’t know are going to be dead,” she said, sighing softly. I’d been feeling guilty all night, and kept wiping tears away; it was hard to concentrate on anything. She knew I was upset and didn’t know what to do. “Listen to the music,” she said, patting my hand, “there is still good in the world, even if it’s hard to find. Just listen.” With that, she poured us more whiskey, and held my hand. I kept crying, but I took her advice.

The war in Ukraine broke out a day after I spoke with baritone Etienne Dupuis. I seriously questioned if this might be my penultimate artist interview, my conclusion to writing about music and culture. It was difficult to feel my work had any value or merit. Last week I wrote something to clarify my thoughts and perhaps offer a smidge of insight into an industry in tumult, but my goodness, never did my efforts feel more absurd or futile. Away from the noise of TV and the glare of electronic screens, there was only snow falling quietly out the window, an eerie silence, the yellow glare of a streetlight, empty, yawning tree branches. Memory, despite its recent (and horrifying) revisionism, becomes a source of contemplation, and perhaps gentle guidance. I thought of that moment with my mother, and I switched on Don Carlo once more. Music and words, together, are beautiful, powerful, potent, as opera reminds us. These feelings can sometimes be heightened (deepened, broadened) through translation, a fact which was highlighted with startling clarity earlier this week during an online poetry event featuring Ukrainian poets and their translators. American supporters included LA Review Of Books Editor and writer/translator Boris Dralyuk and writer/activist/Georgetown Professor Carolyn Forché, both of whom gave very affecting readings alongside Ukrainian artists. (I cried again, sans the whiskey.) The event was a needed reminder of art’s visceral power, of the significance of crossing borders in language, culture, experience, and understanding, to move past the images on DW and CNN and the angry messages thrown across social media platforms like ping-pong balls, to sink one’s self into sound, life, experience, a feeling of community and essential goodness, little things that feel so far. The reading – its participants, their words, their voices, their faces, their eyes – was needed, beautiful; the collective energy of its participants (their community, that thing I have so been missing, for so long) helped to restore my faith, however delicately, in my own abilities to articulate and offer something, however small. I don’t know if music makes a difference; context matters so much, more than ever, alongside self-awareness. Am I doing this for me, or for others? I push against the idea of music as a magically “unifying” power, unless (this is a big “unless”) the word we all need to understand – empathy – is consciously applied. Empathy does not erase linguistic, regional, cultural, and socio-religious borders, but it does require the exercise of individual imagination, to imagine one’s self as another; in that act is triggered the human capacity for understanding. Translation is thus a living symbol of empathy and imagination combined, in real, actionable form – and that has tremendous implications for opera.

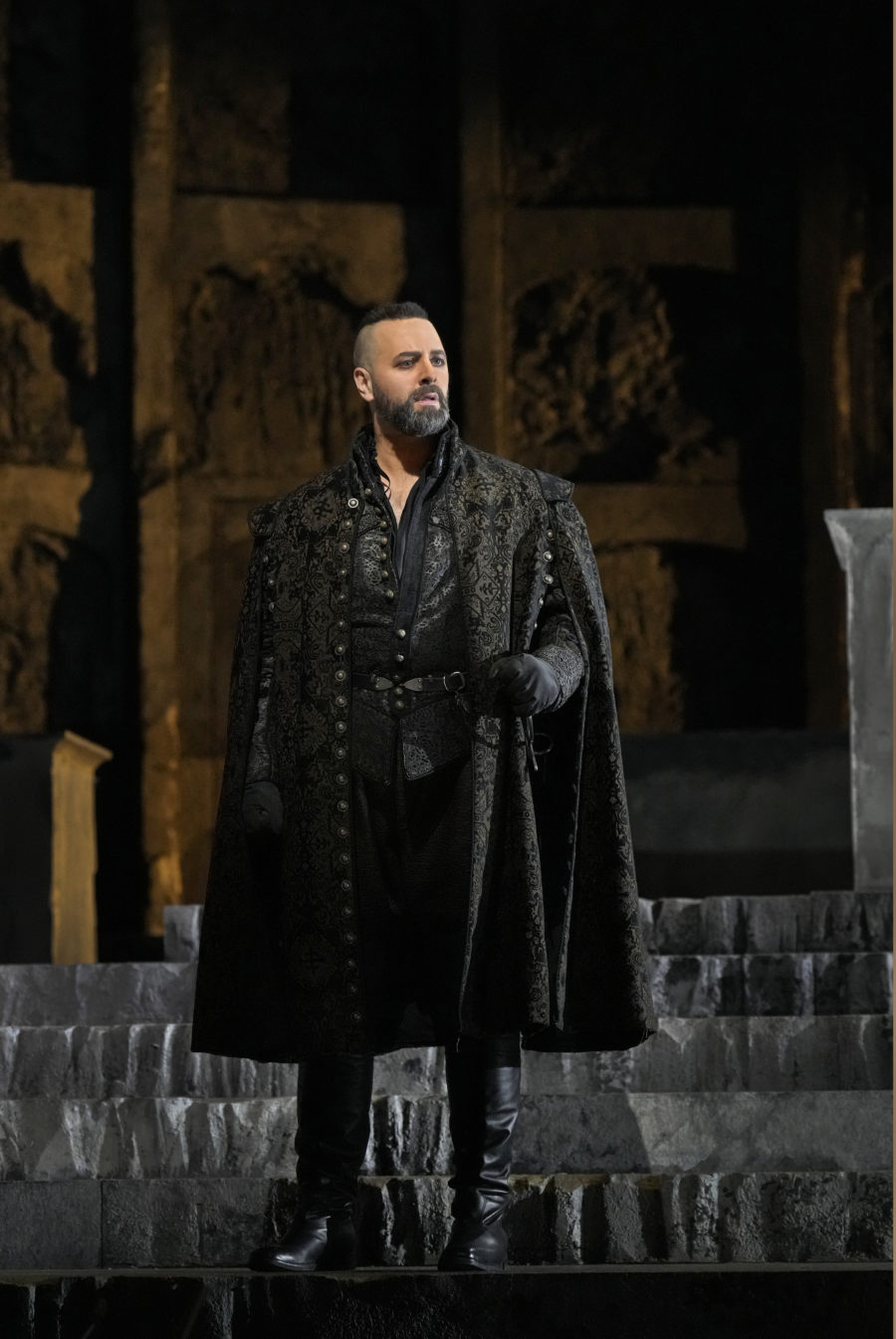

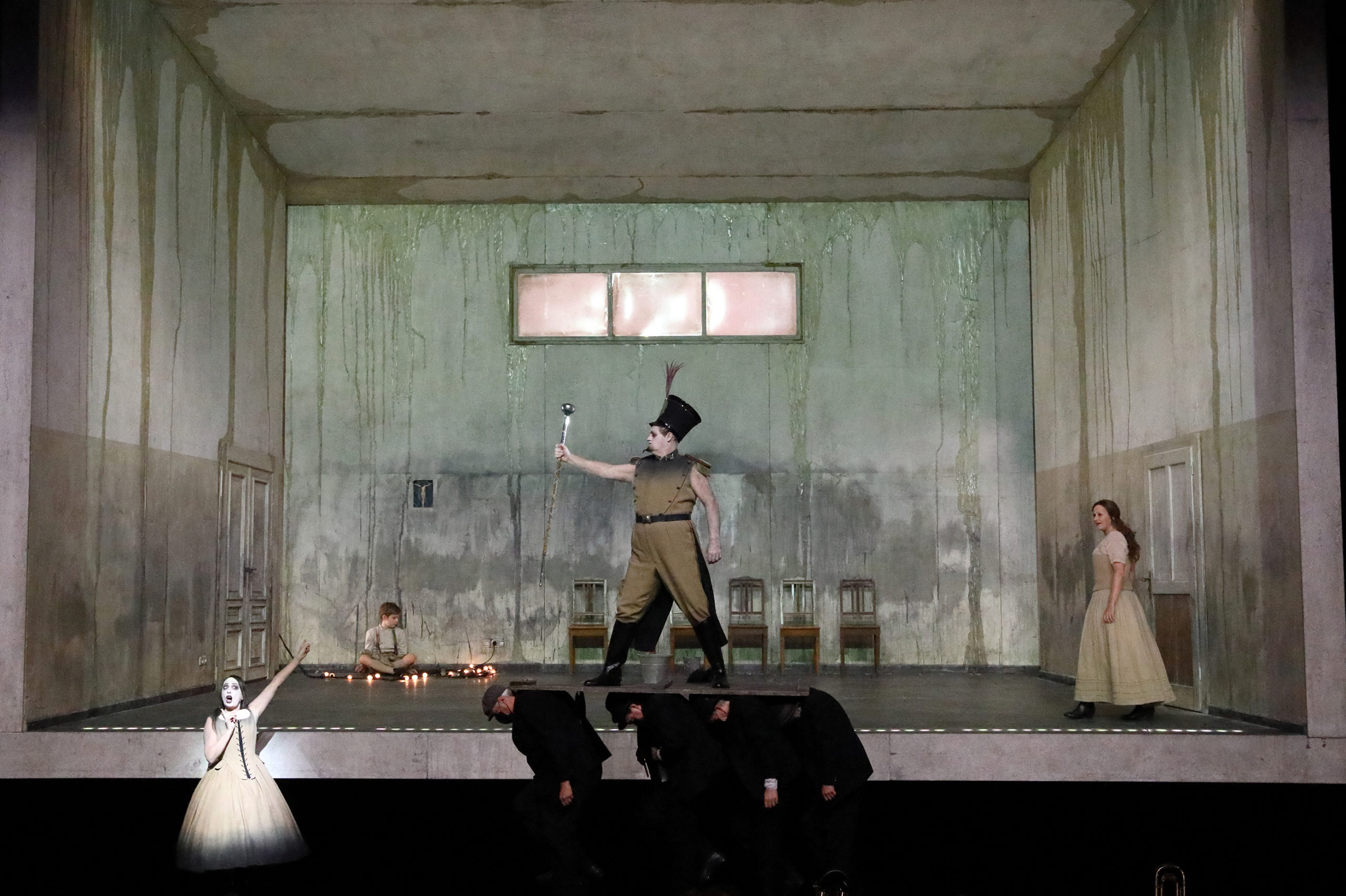

On February 28, 2022, The Metropolitan Opera opened its first French-language presentation of Don Carlo (called Don Carlos). Premiered in Paris in 1867, composer Giuseppe Verdi continued to work on the score for another two decades, and the Italian-language version has become standard across many houses. Based on the historical tragedy by German writer Friedrich Schiller and revolving around intrigues in the Spanish court of Philip II, the work is a sprawling piece of socio-political examination of the nature of power, love, family, aging, and the levers controlling them all, within intimate and epic spaces. The work’s innate timeliness was noted by Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times, who wrote in his review (1 March 2022) that it is “an opera that opens with the characters longing for an end to fierce hostilities between two neighboring nations, their civilians suffering the privations caused by the territorial delusions of a tiny few at the top.” The Met’s production, by David McVicar and conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, features tenor Matthew Polenzani in the title role, Dupuis as his faithful friend Rodrigue (Rodrigo in the more standard Italian version), soprano Sonya Yoncheva as Élisabeth de Valois, bass baritone Eric Owens as King Philippe II, mezzo soprano Jamie Barton as Eboli, bass baritone John Relyea as the Grand Inquisitor, and bass Matthew Rose as a mysterious (and possibly rather significant) Monk. At the works’ opening, the cast, together with the orchestra, performed the Ukrainian national anthem, with young Ukrainian bass-baritone Vladyslav Buialskyi, making his company debut in a smaller role, placing hand on heart as he sang. One doesn’t only dispassionately observe the emotion here; one feels it, and that is the point – of the anthem as much as the opera. The anthem’s inclusion brought an immediacy to not only the work (or Verdi’s oeuvre more broadly), but a reminder of how the world outside the auditorium affects and shapes the reception of the one being presented inside of it. “Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast” ? Not always. Perhaps it’s more a reminder of the need to consciously exercise empathy? One can hope.

The moment is perhaps a manifestation of the opera’s plea for recognizing the need for bridges across political, emotional, spiritual, and generational divides. There is an important religious aspect to this opera, one innately tied to questions of cultural and socio-political identities, and it is an aspect threaded into every note, including the opera’s famous aria “Dio che nell’alma infondere” (“Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes” in French), which sounds heroic, but is brimming with pain; Verdi shows us the tender nature of human beings often, and well, and perhaps nowhere more clearly than here. The aria is not only a declaration of undying friendship but of a statement of intention (“Insiem vivremo, e moriremo insieme!” / “Together we shall live, and together we shall die!”). It reminds the listener of the real, human need for authentic connection in the face of the seemingly-impossible, and thus becomes a kind of declaration of spiritual and political integration. We see the divine, it implies, but only through the conscious, and conscientious, exercise of empathy with one another – a timely message indeed, and one that becomes more clear through French translation, as Woolfe noted in his review. The aria, he writes, “feels far more intimate, a cocooned moment on which the audience spies.” Translation matters, and changes (as Dupuis said to me) one’s understanding; things you thought you knew well obtain far more nuance, even (or especially) if that translation happens to be in one’s mother tongue.

Dupuis, a native of Quebec, is a regular at numerous international houses, including Wiener Staatsoper, Opéra national de Paris, Bayerische Staatsoper, Deutsche Oper Berlin, as well as The Met. The next few months see the busy baritone reprise a favorite role, as Eugene Onegin, with the Dallas Opera, as well as sing the lead in Don Giovanni with San Francisco Opera. Over the past decade, Dupuis has worked with a range of international conductors, including Phillippe Jordan, Fabio Luisi, Donald Runnicles, Oksana Lyniv, Bertrand de Billy, Ivan Repušić, Carlo Rizzi, Paolo Carignani, Cornelius Meister, Robin Ticciati, Alain Altinoglu, and, notably, two maestros who died of COVID19: Patrick Davin and Alexander Vedernikov. It was in working with the latter maestro at Deutsche Oper in May 2015 that Dupuis met his wife, soprano Nicole Car; the two have shared the stage in the same roles whence they met (as Eugene Onegin and Tatyana, respectively, from Tchaikovsky’s titular opera). Dupuis’s 2015 album, Love Blows As The Wind Blows, recorded with Quatuor Claudel-Canimex (Atma Classique), is a collection of songs from the early and mid-20th century, and demonstrates Dupuis’s vocal gifts in his delicate approach to shading and coloration, shown affectingly in composer Rejean Coallier’s song cycle based on the poetry of Sylvain Garneau.

Full of enthusiasm, refreshingly free of artiste-style pretension, and quick in offering insights and stories, Dupuis was (is) a joy to converse with; the baritone’s earthy appeal was in evidence from the start of our exchange, as he shared the reason behind his strange Zoom name (“‘Big Jerk’ is my wife’s pet name for me”). Over the course of an hour he shared his thoughts on a wide array of issues, including the influence of the pandemic on his career, the realities of opera-music coupledom, what it’s like to sing in his native language, the challenges of social media, and the need to cross borders in order to understand characters (and music, and people) in deeper, broader ways. Don Carlos will be part of The Metropolitan Opera’s Live In HD series, with a broadcast on March 26th.

Congratulations on Don Carlos…

It’s beyond my greatest expectations, really….

… especially this version! When you were first approached to do it, what was your reaction?

It was a surprise! For some reason, even though my first language is French, I do get offers for Italian rep all the time. I think I have an Italianate way of singing – I’ve never given it much thought. When Paris did Don Carlo exactly the way The Met is doing it – the five-act French version, then the five-act Italian version a year later with the same staging – even though I’m French, not France-French but Quebec-French, they cast me in the Italian version. So when The Met called and said, “We want you for the French version” it was very exciting and surprising, I was able to sing it in the original, which is my original language as well.

Being in your native tongue has you changed how you approach the material, or…? Or changed your approach to Verdi overall?

There are things I think I’m better at and things I think I’m worse at! It’s important to know that David (McVicar) and Yannick (Nezet-Seguin) have together decided on a French version that has a lot of the later Italian version’s music in it – so, for example, they’re using a French version most of the time, but the duet between me and the King, or the quartet in Act 4, is the revised Italian version, in French. They worked on a version which they felt made the music and the drama the clearest possible – that’s important to establish. The creation from 1867 isn’t what people will get. But my approach in terms of the language, it’s not the vowels or language, so much as the style. So it’s really cool, I’ve always liked hybrids, even in people who come from different backgrounds, like if one person is born in one place but raised in another, for instance – I think it’s interesting. And I love the writing of Italian composers, those long, beautiful legato lines – and in this opera, with the French text, it’s especially interesting because the text fits differently than you would expect. It doesn’t necessarily fall in the obvious places, especially when it comes to stresses. Italian sings differently than when you speak it, so the music of the language is different – and that translates live. I’ve done Don Carlo five times already my last one was in December so it’s very fresh in my head

Does that give you a new awareness of Verdi’s writing, then? You said in a past interview that his is music you can “can really live in” but this seems as if it’s making you work to build that nest for living…

Oh for sure. In general – and this is very stereotypical – the Italian, and I put it in brackets, “Italian” really, it’s emotional first… like, we’re going to go to the core! It’s so big with the emotion, and the French goes more into, I want to say a sort of intelligence but I don’t mean it against the Italian! It’s that in French, the characters are in their heads, they rationalise the emotion, so they’ll say “I love you” differently, spin it in a different way. The word we use is “refinement” – there is a refinement in Italian too. I want to be clear on this: the French and Italian influence each other, but I do love singing it in French because all the nuances I’ve seen in the score, in French they make sense to me. “Why is there pianissimo in that note?”, for instance – and in French, it works, those choices really work. It changes the way the line is brought up, like, “oh, that’s why it’s that way!”

Jamie Barton as Princess Eboli and Etienne Dupuis as Rodrigue in Verdi’s “Don Carlos.” Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

So is that clarifying for the understanding of your character, then?

Yes – the short answer is yes; the long answer is, it has to do a lot more with the background in the sense that now I realise what they’re really saying. Of course it is the fact I speak the language, so now I mean, I’ve always known the phrase he was saying, but in French the translation is almost exact. There are these little differences, and they give me more insight into what’s going on.

I was talking with Jamie Barton about this yesterday – we all love each other in this cast, I’d sing with them all, any day of my life, for the rest of my life – and she and I were talking about this one particular scene. It’s a very strange scene before my first aria, the French court type of music, it’s not that long. My character just gave a note to the Queen in hiding, and Eboli saw I did something, and she has all these suspicions, so then she starts talking to me about the court of France and it’s the weirdest thing; I’ve always had trouble with that scene when I did it in Italian. Why is she so intent on asking me about the court of France? I don’t see Eboli caring that much, but the answer was given to me partly by McVicar, partly by Yannick, and partly through the French version. At this very moment (Rodrigue) has been supposedly sent to France, but he’s been in Flanders the whole thing trying to defend the part of the empire he loves – it’s not just he loves it, but he wants to defend human life, and so Eboli is not in a position to say to him, “I want to know what the Queen is up to” – so she attacks me, but it’s in the form of, “How’s France?” Even though she knows I’ve not been there at all, she’s that clever. It’s why she’s so relentless. “What do women wear in France now? What is the latest rumour?” My answer is, “No one wears anything as well as you.” I’m deflecting every question. This very short two-minute scene that everyone wants to cut – it’s very rich in subtleties! And because of the French language now, I think it’s become much clearer in my mind. In the French language sarcasm is very strong, we use it all the time, so.

Sonya Yoncheva as Élisabeth and Etienne Dupuis as Rodrigue in Verdi’s “Don Carlos.” Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

So it’s political-cultural context, for him and for us…

Yes, exactly. Eboli is very clever, fiercely clever, she’s a force to be reckoned with, so it establishes the two characters, her and Rodrigue. They are just behind the main characters: Don Carlo and Élisabeth and the King. Eboli and Rodrigue are both in the shadows, but quickly, just in this little scene, you understand they are pulling the strings in many instances. I become the best confidant of the king and I am already the confidant of Don Carlo; Eboli is sleeping with the King ,and she is pulling the levers with Élisabeth.

So you see the mechanics of power in that scene very briefly…

In a short way, yes. It’s one of my favourite moments of the opera now. We can blame the fact that, in the past, I should’ve coached with someone who knew the opera really, really, really well, and said, “Listen this is what’s going on” – I mean, it has been said to me, but it wasn’t that clear. I knew Eboli was relentless about the court, but what is really happening? It’s really about the power struggle of these two. That dynamic is one you find the trio with Don Carlo later on – the same thing happens. It’s real people fighting for what they believe is right.

There are some who, especially after this pandemic, have felt that the return of art is a wonderful sort of escape, but to me this particular opera isn’t escapist, it’s very much of the now.

There is an inclination to think of it like this: opera can affect your everyday life – and almost any opera can. And Don Carlo definitely should be something people see. They might think, “Wow, there’s so much in today’s politics we can with this.” There are always people pulling the strings when it comes to politics. When you see someone in power do something completely crazy, this opera reminds you that there are people in the back who might have pushed those rulers to that, it’s not always, exclusively just them waking up and going, “Hey, let’s do something awful today!”

It’s interesting how the pandemic experience has changed opera artists’ approaches to familiar material, like you with Rodrigo/Rodrigue, Don Giovanni, and Onegin… is it different?

Completely, and it’s not just the roles either, but the whole career. When you jump into it – and it’s the right image, you do jump, you don’t know where it takes you – at first you have a few gigs, smaller roles and smaller houses. You ride that train for a while and if you’re lucky, like in my case, you get heard and seen by people who push you into bigger roles and houses, so that train keeps taking you this place and that, and you never stop, it becomes unrelenting: when do you have time to stop for a minute and say, “Do I still like doing this?” We have people ask us things like, what’s your dream role? And I don’t know the answer. I kind of have an idea, and I have dreams, but was it a dream to sign at The Met? No. Was it a dream to sing in a produiton like this? Yes, a million times, yes. So it’s not just “singing at The Met”, but it’s a case of asking, in what conditions do I want to sing there? To totally stop during the pandemic and think, “Do I still like doing this? How do I want to do it now?” was, for me, very important. One of the first things that happened as things went back was that I had to jump in at Vienna for Barbiere – it was a jump-in but I had three weeks of rehearsals, and it was amazing. I’d done Figaro many times and it was the most relaxed I’ve ever done it.

Really!

Yes! It was complicated and high singing, sure, but, I’m going to be serious here: I took three days after each performance to recuperate because of how much I moved around and the energy I gave. I’m older – I tried to do it like when I was 28, but I had to recuperate as the 42-year-old man that I am. People said, “but you look so young on stage!” I said, “Oh my god, I feel so tired!” Still, I was really, genuinely relaxed about it all – the role just came out of me – I just let it go! I don’t feel like my career hangs on to it, or to any other role. I don’t feel it’ll stop me from doing things; one role doesn’t stop me from the other.

You were supposed to be in Pique Dame in Paris last year.

It is an amazing opera, it’s not about the baritone at all, so it’s not like Onegin, but what I know of Lisa and Herman’s music, well, I want to see and hear that, it’s amazing! But at the same time, I am interested in the baritone version of Werther – I can say honestly, it was one of the roles I’d wanted to do – it’s not a lover, Charlotte and Werther don’t have that beautiful love story…

… neither do Onegin and Tatyana…

Exactly! It is profound, the way it’s written.

Returning to your remark about teams, you worked with two conductors who passed away from COVID, Patrick Davin and Alexander Vedernikov. What do you remember of working with them, and how did those experiences affect working with various conductors now?

With Davin, we did two productions together; he was a different type of man. I never got with his way of making music so much but there is something you feel when people you know passed away -– and he was still one of the good guys, he was still fighting for art and beauty, even if we had different ways of doing it, it doesn’t matter. With Vedernikov, I met my wife singing under him in Berlin –he was the conductor of Onegin, and she was Tatyana. At that time I was doing my first Rodrigo, and my first Onegin. I was learning those two roles together, and the first premiere of Don Carlo fell on the same day as the first day of rehearsals for Onegin; I had both roles together in my brain, and it follows me to this day. In fact, my next gig is in Dallas, singing Onegin, a week after the last performance here, so the roles are forever linked for me.

Nicole and I met in this production of Onegin with Vedernikov, and I remember looking at the cast list and seeing his name, and thinking, oh no! I was nervous, because he had been the conductor for over ten years at the Bolshoi, so Onegin and Russian music overall poured out of him. It was my first time singing in Russian, and I thought, “Oh my God, what will he say about my Russian!” But he was the nicest, most relaxed man I ever met. He had this face conducting… it wasn’t grim, he had these really big glasses going down his nose, and he was conducting, head down, very serious and thinking, and sometimes he’d give you a comment, like, “We should go fast here.” I kept worrying that, “Oh no, he’s going to say my pronunciation is terrible” but no, he was giving me the freedom, saying things like, “make sure you are with me.” He taught me so much by leaving out some things. This one day, we had this Russian coach, she was really precise – I love that, it allows me to get as close to the translation as I can – and there’s a moment, I forget the line, but she was trying to get me out of the swallowing-type sounds that sometimes come with the language, and one word she was trying to get to me be very clear on, and Vedernikov turns around and goes, “That’s all fine but but he also has to be able to sing it.”

It’s true in any language. I speak French, and this whole (current) cast of people speaks French (Sonya Yoncheva’s second language in French; she lives in Geneva) and even though there are moments where I want to turn around and go, “Be careful, it doesn’t sound clear enough” – I think, let it go, because I think, and this is from Vedernikov, you have to be able to sing it. It’s an opera. And now that he’s passed away I really remember that, more and more. I think it’s the power of death, to highlight any little bits of knowledge or experience you gain from working with and knowing these people – you cherish them and what they brought.

How much will you be thinking of that in Dallas?

Every time, of course. Especially since I’m doing it with Nicole as Tatyana!

You guys are an opera couple, but do you ever find you want to talk about non-music things?

We almost never talk about opera. We’re not together now but even if we were, we have a little boy, so we talk about that. We have projects, we’re thinking where we’ll go live next and where Noah will go to school, and depending on how many singing opportunities come our way from different opera houses – that influences where we want to be. Should we be closer to those gigs, or… ? If she sings two or three years in a specific house, then maybe we should be as close as possible there? We talk about our families, our friends – humans are what matter the most to Nicole and I. Of course we talk about random gossip too, and what people post on social media. Sometimes we chat with each other about work since we are opera-oriented but we barely sing at home, mostly because Noah hates it.

You mentioned social media – some singers I’ve spoken with have definite opinions about that. It feels like an accessory that has to be used with a lot of wisdom.

For sure, but when it comes to opera singers, I have yet to see, maybe there’s an exception, but I’ve yet to see people really going into the controversial areas, except for a few. There are ones out there who like to impart and share their own experiences and knowledge of the world of opera, and they do it in a way in which people are interested, but… I’m torn on it, because it’s not the same for anybody. This is one of those businesses where you are your own product, everything that happens to you is so unique; I can tell you things about how I feel about the operatic world and it would be different to someone else’s. So I don’t mind if they share it, every point of view is important, but there’s definitely no absolute truth to what any of them are saying. To come back to your point about social media as a tool, we’ve noticed more and more it will make someone more popular in some senses – singers have been struggling for a long time with popularity. Opera used to be mainstream, and it’s been replaced by cinema and models, like spotting an actor vs an opera singer on the street is very different – people freak out over the actor, of course! So it’s kind of like the operatic world is trying to gain back some of that popularity it once had. I mean, we’re great guests (on programs), we have good stories, we’re mostly extroverted and loud…

But most of the postings don’t convert into ticket sales…

No, but they convert into visibility. So 50,000 people may not buy tickets, but they can be anywhere in the world…

… they don’t care seeing you live or hearing your work; they just want to see you in a bikini.

Ha, yes!

Your remark about visibility reminds me of outlets who say “we don’t pay writers but we pay in exposure”…

Yes, and that’s bullshit. In the world of commerce, there’s an attitude from companies of, “We’ll pay for an ad on your page” and it can work, but as a product, we don’t behave the same way a pair of jeans does; I can’t ship myself to someone, and if I don’t fit I can’t be returned. It’s a completely different way of marketing. You can’t market people in the arts the same, and you shouldn’t.

You have had to develop relationships with various houses and have worked for years with your team to develop those relationships, but things can change too.

That’s right, and I’ve already seen part of the decline, not for me, but yes. As human beings we will go really far into something until it repeats, and crashes, and as it crashes, we do the opposite, or try something else, and we do that over and over and over again. Big companies reinvent themselves enough they can find longevity; it isn’t the same for artists. If you think of how a company like Facebook began, there was a time not that long ago, it was like, “Oh my God, my mother is on Facebook!” Now it’s like, “Oh yes, there’s my mom.” That’s become a normal thing; that’s the evolution. And along with that you start to notice other things – for instance, I posted a photo of my hairdo on Don Carlo and I got a few flirtatious comments from men, people I don’t know, and I thought, “Wow, that was just one picture!” It made me really think about what women who post certain shots must face.

Yes, and most women, me included, will use filters – it’s a purposefully curated version of self for a chosen public, not real but highly self-directed.

It’s worth remembering: a picture is not a person, and no one seems to make the distinction anymore. That extends to the theatre: you see someone onstage, and you go and meet them backstage, and you can see clearly that they’re so different — a different height, a different shape, everything, even their aura is totally different from the image you were presented with. And sometimes it’s a shock. Sure, through photoshop and airbrushing, a photo can be good, but even onstage, a person is still not the same person, or in a TV show or whatever. It’s a picture; it’s not you.

Matthew Polenzani as Don Carlos and Etienne Dupuis as Rodrigue in Verdi’s “Don Carlos.” Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

That’s palpable in the recording, and I hear something different every time. Listening to the left hand can really bring something alive that one thought one knew well.

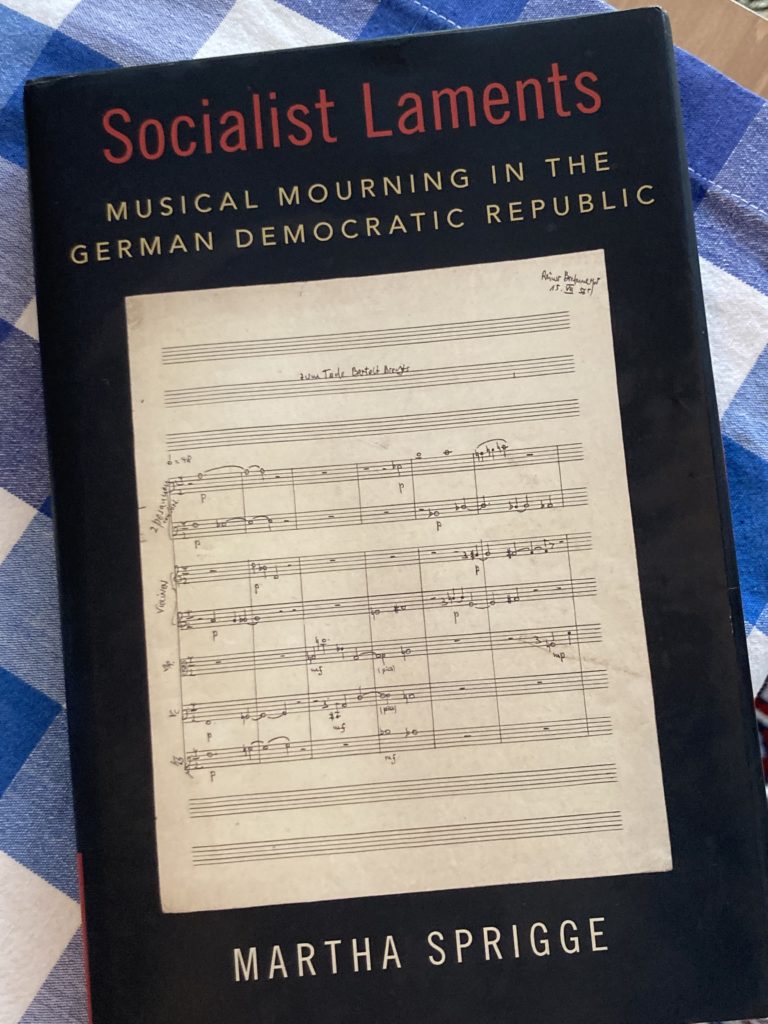

That’s palpable in the recording, and I hear something different every time. Listening to the left hand can really bring something alive that one thought one knew well. Why did you focus on mourning and the music associated with it? You outline some academic motivations in the book but I’m curious about personal instincts.

Why did you focus on mourning and the music associated with it? You outline some academic motivations in the book but I’m curious about personal instincts.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.