The end of January may be grey and cold, but online the time is considerably enriched by various classical artists and organizations marking Schubert’s birthday. The German composer (1797-1828) is known for his beloved song cycles Die schöne Müllerin (1823), Winterreise (1827) and Schwanengesang (1828), all of which use texts by German writers and poets to explore deeply human experiences – wonder, longing, love, sadness, loss.

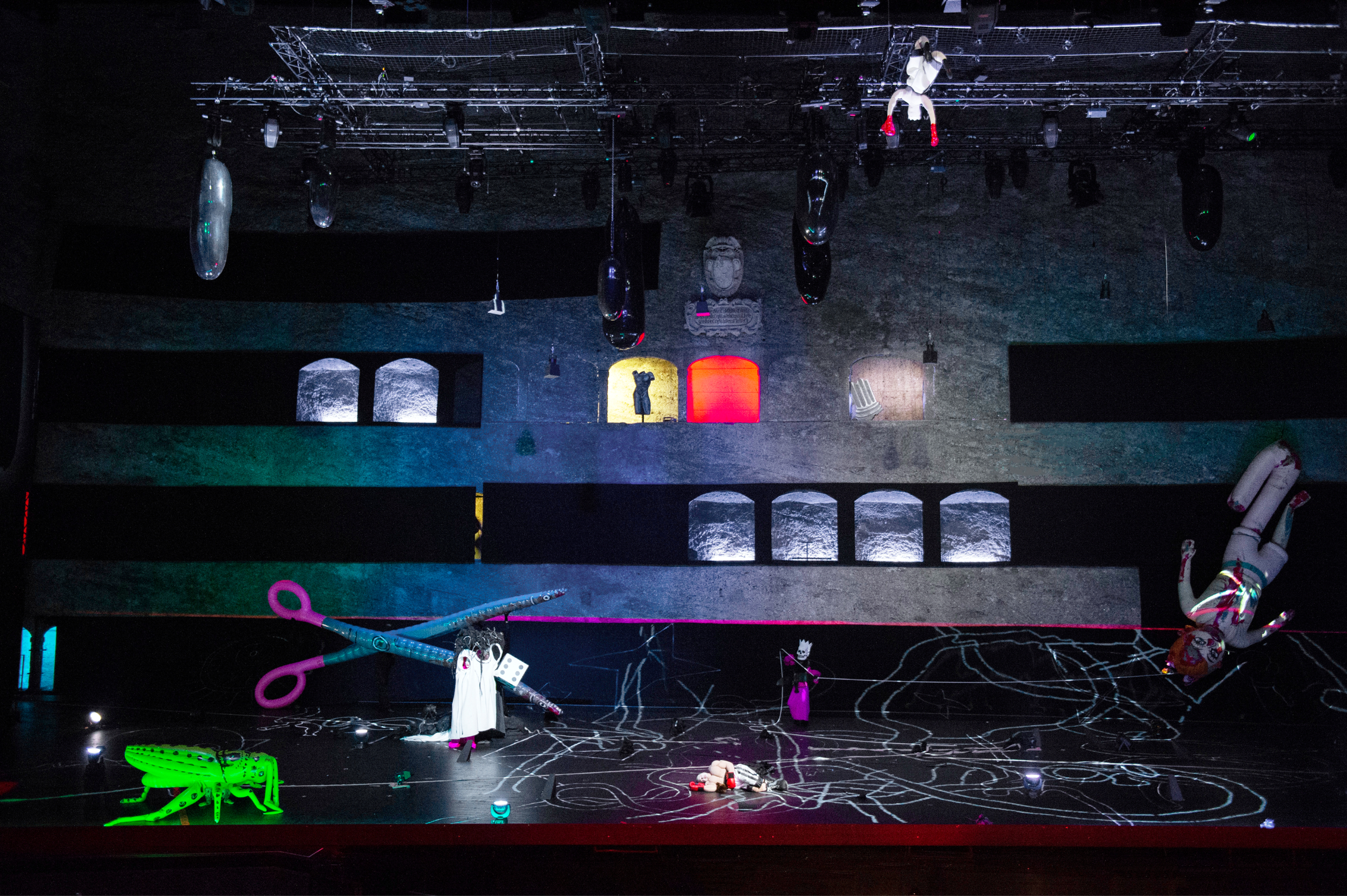

Opéra Comique is offering their own thoughtful salute to the composer with L’Autre Voyage (The Other Journey), opening on 1 February. Combining selections of Schubert’s music with fragments of poetry (by Heine, Goethe, and others) the work features the central figure of a forensic doctor whose recognition of his dead doppelganger catalyzes important personal explorations. With direction and libretto by theatre artist Silvia Costa and musical direction by Raphaël Pichon, the work offers a fascinating insight into the lasting impact of Schubert’s oeuvre as well as the text that fuelled his creative inspiration and continues to inspire its interpreters, including Voyage lead Stéphane Degout.

The French baritone’s passion for text and music has translated into an immensely engaging approach over baroque, classical, romantic, modern, and contemporary repertoires. Degout has sung title roles in a number of famous works including Monteverdi’s Orfeo and Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria, Debussy’s Pelléas et Melisande, Conti’s Don Chisciotte, Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, and Thomas’ Hamlet. He has graced the stages of Opéra de Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Berlin Staatsoper, Bayerische Staatsoper, Theater an der Wien, Teatro alla Scala, De Nationale Opera in Amsterdam, Opernhaus Zurich, Lyric Opera Chicago, and The Metropolitan Opera in New York. Festival appearances include Salzburg, Saint Denis, Glyndebourne, Edinburgh, and Aix-en-Provence. In 2022 Degout won the Male Singer of the Year at the International Opera Awards, and the following year became Master-in-Residence of the vocal section at Belgium’s prestigious Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel, having been recommended to the role by baritone José van Dam, the organization’s then-Master-in-Residence. The two baritones share a long history, having first appeared onstage together in a 2003 production of Messiaen’s Saint Françoise d’Assise at the RuhrTriennale.

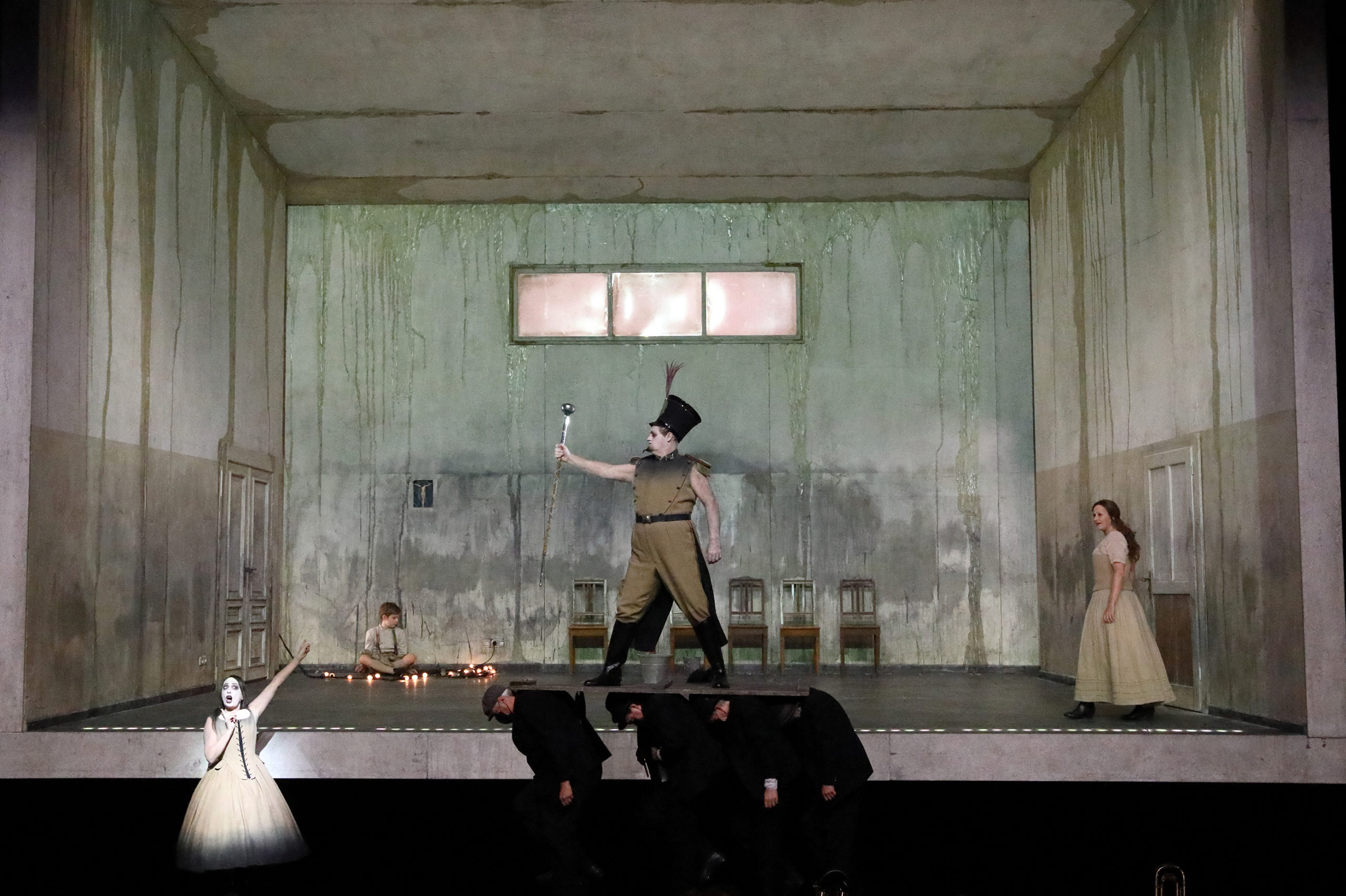

Degout has also worked extensively with conductor Raphaël Pichon and his Pygmalion ensemble, onstage, on tours, and across a range of lauded recordings. The 2018 album Enfers (harmonia mundi) features a deliciously dark selection of works by French composers (Gluck, Rebel, Rameau), while 2022’s Mein Traum (harmonia mundi) explores dreams via pieces by Schubert, Weber, Schumann, and Liszt. This past December Pichon led his Pygmalion on a European tour of Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah with Degout as a soloist alongside Siobhan Stagg, Ema Nikolovska, Thomas Atkins, and Julie Roset. But famed historic works are not, as was mentioned, Degout’s sole territory; the baritone has performed and often been directly involved with the creation numerous contemporary operas, including Benoît Mernier’s La Dispute (2013), Philippe Boesmans’ Au Monde (2014; both La Monnaie), and Pinocchio (2017) also by Boesmans and commissioned by the annual Aix-en-Provence Festival. British composer George Benjamin wrote the role of The King in his intense 2018 opera Lessons in Love and Violence (premiered at at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden) specifically for Degout’s voice.

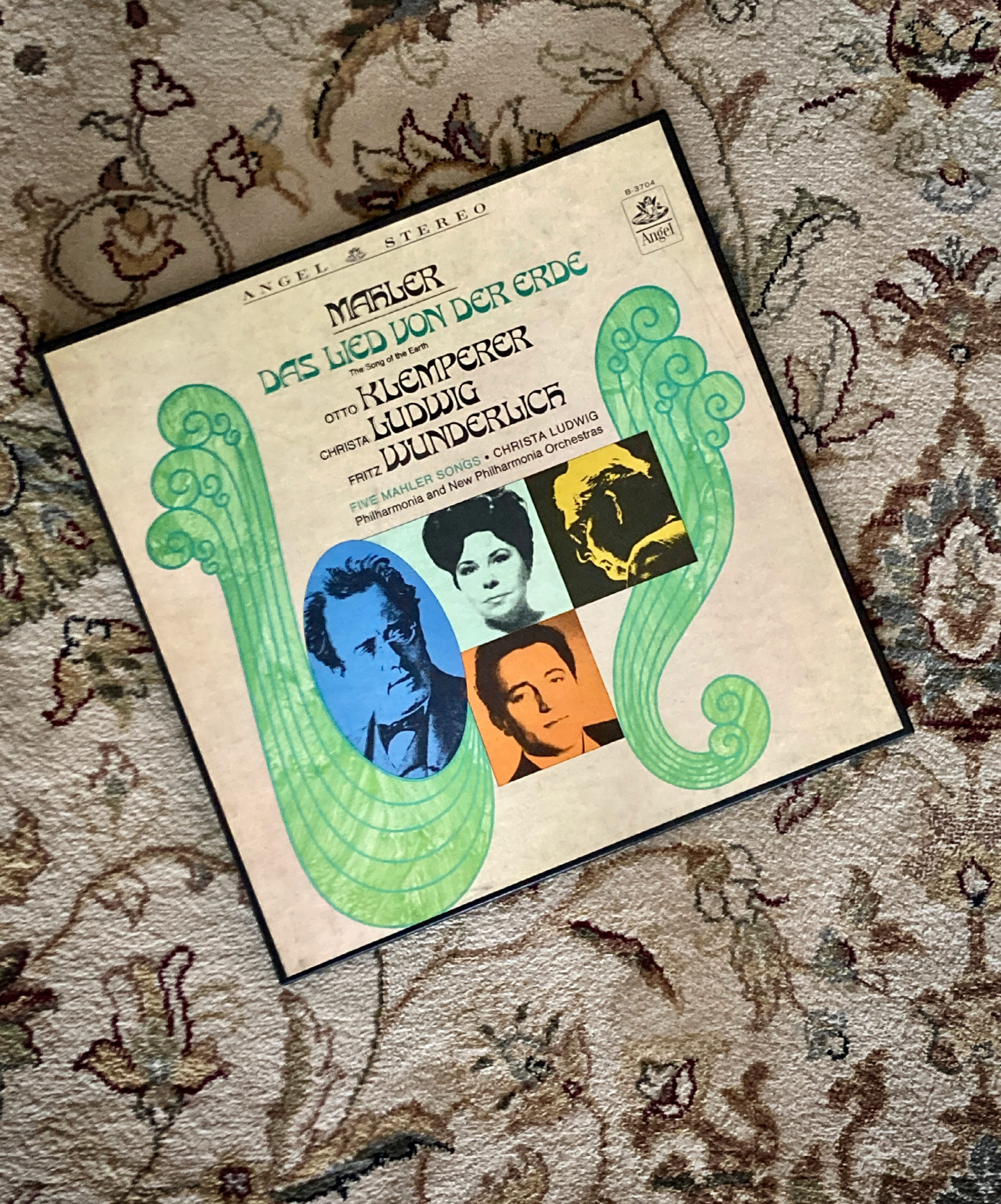

That voice is as much at home in intimate settings as opera stages. His 2021 performance as the title character in Berg’s Wozzeck with Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse garnered high praise from French media, with music magazine Diapason praising the singer’s mix of power and delicacy and proclaiming “Victoire absolue pour Stéphane Degout”. Such a special combination of intensity and lyricism was shown to full effect in 2022 with chamber orchestra recording of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (b.records) with French ensemble Le Balcon, and in 2023, via Brahms’ song cycle La Belle Maguelone (b.records) in a recording captured live at Théâtre de l’Athénée Louis-Jouvet and featuring pianist Alain Planès, mezzo soprano Marielou Jacquard, and speaker Roger Germser. This spring Degout will be using his magical blend of power and sensitivity in the little-known opera Guercœur with Opera national du Rhin. The work, penned by French composer Albéric Magnard between 1897 and 1901 but only presented live in 1931, wears its Wagnerian influences on its sleeve while deftly distilling both the grandeur of late Romanticism and the immediacy of European song craft.

Such a blend of music and narrative seems central to the more immediate L’Autre Voyage, described by Opéra Comique’s Agnès Terrier as “Ni reconstitution, ni nouvel opéra” (neither reconstruction nor new opera). Instead, Voyage positions itself as a wholly original theatrical piece showcasing the very things that so informed Schubert’s creativity, not to mention the public’s continuing fascinating with him: “le doute, la fantaisie, la solitude, l’élan spirituel” (doubt, fantasy, solitude, spiritual impulse). Voyage runs through mid-February and will be recorded by French public broadcaster France Musique for March broadcast on Samedi à l’opéra. Degout will also be presenting a recital of Schubert’s famed Winterreise with pianist Alain Planès at Opéra Comique on February 14th.

Earlier this month the busy baritone took time out of his rehearsal schedule to share thoughts on the importance of text, not taking one’s mother tongue for granted, and the important reminders teaching offers.

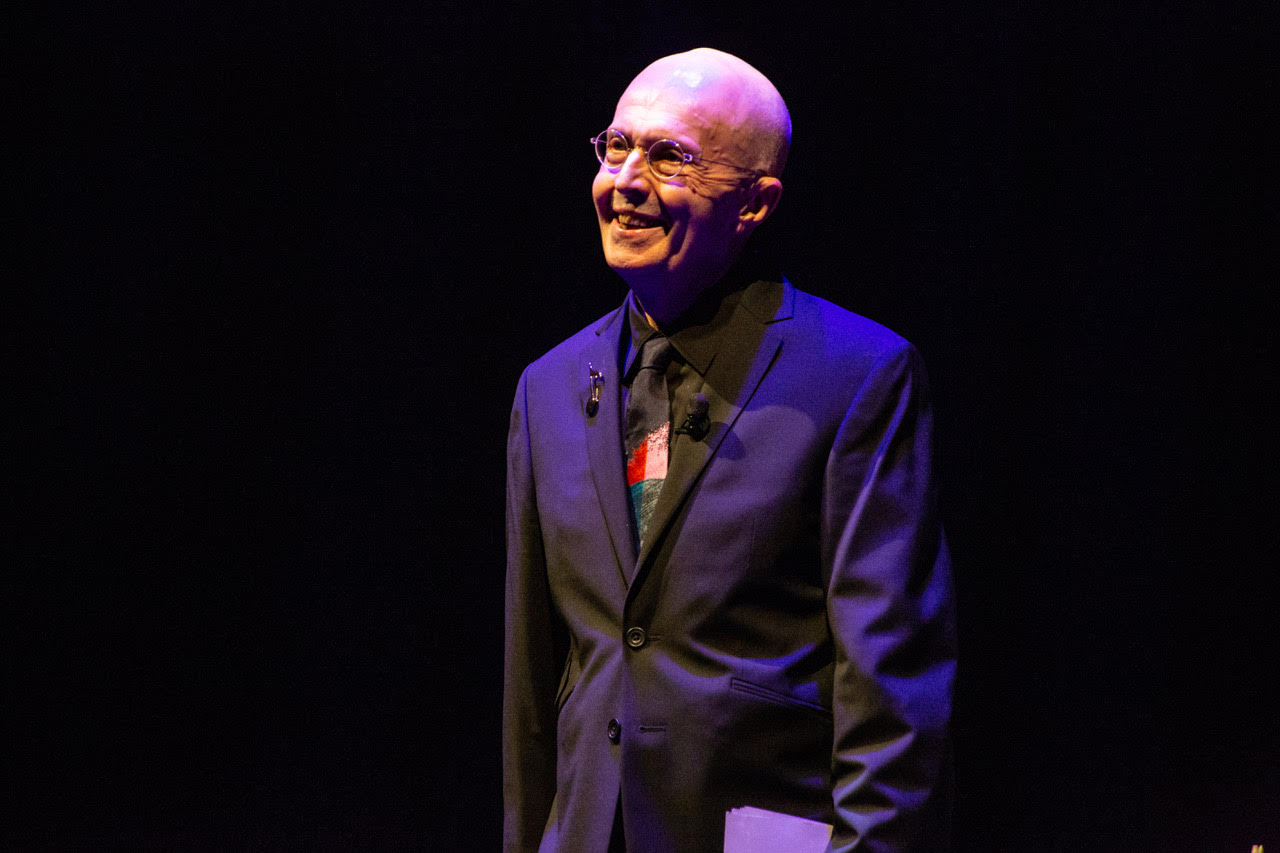

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Millot

How extensively do you study the immediate text as well as contemporaneous writing and music?

I always do this for every part I sing. I like to know the contextual things – poetry, literature, history, everything – it’s very interesting how it just puts me in, I wouldn’t say the mood, but offers clues and connections with the time of the music. This particular period of Schubert’s is very rich in opera works of course, but every country and every culture has a specificity and I study that accordingly. I will sing Onegin in June, and though it’s later in the 19th century than Schubert, it also has a great connection with Romanticism of the 19th century. So yes, I do read a lot!

To what extent do you think mood in music shifts according to the language, especially for something like L’Autre Voyage?

I’m not sure if you’ve seen the series of conversations between Daniel Barenboim and Christoph Waltz, but in one of them Barenboim says it’s obvious in the music of some composers what their mother tongue is. So it’s obvious with Beethoven that he’s a German speaker from the way he writes music and puts harmonies together and places weight on certain elements within bars – that thinking extends to works in German, French, Russian. I don’t know Russian well enough to be aware, but such an idea is obvious to me in French and German. (Barenboim) also deals with the tempo, that you can’t do the music faster than the maximum you can speak or sing the language – sometimes the centre gives. It’s a sort of technical point, but the mood is given by the language, by the construction of the phrase – and as you know, German has a specific grammar where you have to wait for the end of the phrase to really know the whole thing.

When the language itself is used within a poetic construction, it’s beautiful for sure but it’s also more difficult; you have to be able to get everything at the same time in order to really get it. With L’Autre Voyage sometimes there are altered phrases and words to make connections between these different works more logical – Silvia Costa changed the text, but she worked very carefully on being as close as she could to the original linguistic specificity.

Stéphane Degout (L) and Siobhan Stagg (R) with Chœur Pygmalion in L’Autre Voyage at Opéra Comique. Photo: Stefan Brion

“I’m very close to the text”

How have these working relationships influenced your approach to different material, whether it’s new material or historical material?

Maybe it’s because I’m a baritone, it makes me more, let’s say… on the spoken side of the music. I’m very close to the text, it’s something I also happen to love – poetry and the languages , talking, conversation. I’ve been lucky because almost all of my repertoire is really based on the language. If we stay with French repertoire, Rameau and the Baroque stuff I did with Raphaël, it’s singing on the notes, it’s declamation, it’s clarity. With German lieder and composers like Wolf and Schubert and Schumann, they all have such respect for the primary material they have – the text and the poetry – so you can’t forget the music, but it’s not the music that drives you through the text; it’s the text that drives you through the music. It’s even more obvious to me because I’m a native French speaker – these things come immediately to my ear. With works by composers like Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, it’s clear they all have first read the respective texts and fallen in love with them, and thought they could make something with the music. But the text – it’s not an excuse to make music; it is the central point of all things. Perhaps I notice this more because when I was a teenager I did theatre and so more talking than singing on stage, I don’t know! (laughs)

As a native French speaker, what’s it like to return to singing in your own language?

The difficulty when we sing in our own language is that we don’t care so much. It is this feeling of, ‘well it’s my language so I don’t need to make an effort’ – but I know I do need to make extra effort. I speak German, I have studied it, so it gives me a sort of extra comfort in singing it; I know the structure and pronunciation but occasionally there I also need a bit of an extra hand, someone to say, ‘it’s right but it doesn’t sound German, it sounds like a foreigner talking in German.’ These language explorations are really fascinating. I have been working with young singers for a few years now and we talk a lot about this issue, and it’s great to see that they have the same comforts and difficulties that I had 25 years ago when I started. It’s a common thing.

What has teaching given you as a singer? What are its challenges?

The difficulty of teaching is putting words on things I do naturally. I’ve been singing professionally for almost three decades now; I don’t need to think very technically or consider what I’m doing physically – it’s just here. But when I have to help a young singer who is struggling with some technical things, breathing issues or whatever, I need to explain exactly, because I hear what’s wrong but need to help to correct it clearly, and this is the difficulty. So, I’m learning to teach, let’s say. It’s sort of a mirror of my own experience, and sometimes hearing a young singer struggling makes me think of the way I’ve done things myself when I was struggling with those same issues.

“Every body is different, every voice is different; it’s not an instrument made in a factory”

Has teaching created a deeper awareness of your own approach?

Yes, very much! We did a concert in Belgium in November, I was one of the singers, and during the concert I realized I didn’t do what I said to the others in the days before when we were rehearsing. Basically I joke about things like that and say: do as I say, not as I do!

There’s also value in being honest with students and saying, “Look, I can teach you the basics, but with some things, my system works for me and it might not work for you.”

Yes, there are basics – breathing, using muscles, pronunciations – but everyone eventually has their own technique, because every body is different, every voice is different; it’s not an instrument made in a factory. Every instrument maker will tell you every instrument is unique…

… and different experiences and backgrounds – context – which will influence what comes out. How does that influence your work with living composers?

It’s been interesting. With George Benjamin, for instance, the work was very specific. He was extremely precise with his own work and what he wanted. It’s exactly what I said before, the text and respect for it, George is really into writing music where the text is very clear and natural. He used virtuosity in his writing for Barbara (Hannigan) because she has this big range she can use, but for me and my character, he used the spoken side of my voice. When he and I first met, I was still in my Pelléas time, with this very clear, high sound; he gave me the score and I saw the part wasn’t written that high – it was surprising – but in working on it and learning the music, I realized that he there was no need to write something that was more important than the text. That’s the way I understood it.

How collaborative was the atmosphere?

I felt very comfortable and confident with him as a conductor, because of course he knew his work well, so he could help us in the meanings as well as the performing. He changed maybe three things with me, things which were more related to the length of notes and breathing; the changes were more naturally aligned to my own way of singing than what he’d written for me.

I don’t know if you know, we met about two years before the presentation, and spent an afternoon together; he was measuring my voice in every direction, how high, how low, how big, how soft. It was quite intimidating and impressive at the same time. He remembered every aspect of my voice from that day, so the part was perfectly written. Also Martin (Crimp, librettist) and other poets had their own music which sat within the material, I can’t quite say what it is because English isn’t my first language – but I knew it was specific, that it was text which involved not merely giving information on the situation. It also helped that (director) Katie Mitchell was observant of our specifics around how we move and speak.

You’re doing another new-ish opera, Guercœur, in the spring. There are so many operas which are only now coming into the public consciousness…

… yes, it’s true. Guercœur was the idea of (Opéra national du Rhin General Director) Alain Perroux, who has wanted to do it for a long time. I didn’t know about this opera before he told me about its story. The work has, as you probably know, a very unusual history. The composer died before he ever heard this music done live, two-thirds of the original score was lost in a fire, but (composer/conductor) Guy Ropartz saved some and reconstructed the orchestration. It was recorded in 1951 and again in 1986 with a cast that included José Van Dam, and only presented live once, in Germany in 2019 – and this is an opera written more than 100 years ago! The presentation in the spring feels as if it will be a new creation itself, in a way.

“When he sang, I could feel the vibrations”

You mentioned Van Dam, who indeed is part of the recording of Guercœur – can you describe his influence?

When I was in the Conservatoire we listened to a lot of his CDs and everyone liked his voice very much. And though we don’t have the same repertoire really, he was the type of artist I wanted to become when I was young. I first met him over twenty years ago when we did Saint François d’Assise in Germany – I was so impressed to be onstage with him. At that time I was singing the role of Frère Léon, the novice of St. François. There’s a moment in the first scene of the opera where François talks with Léon about different things; in the staging Van Dam was next to me, with his arm around me, so our bodies were basically in contact from shoulders to the knee. When he sang I could feel the vibrations – from shoulder to the knee. That was a non-talking lesson, maybe the best one I ever had, and I thought, okay, this is singing; singing is not only involving the mouth – it’s the whole body. That was such an emotional moment. I’ve worked with him since, and we have a great confidence with each other.

I’m very lucky and happy he asked me to replace him at the Chapel. We don’t really talk about this but I can feel we have the same sort of way of doing things, of approaching the music, of being onstage. I’ve seen him teaching there; he doesn’t say much, but does speak about text, diction, language, and that one should be right about the vowels – those small but important details. They’re the key, and I totally agree with him. I’ve always perceived Van Dam as a very calm person, with his feet planted on the earth, that it all comes naturally. I’m also this kind of person, I think – earthy – so yes, it is a special connection indeed.

Acknowledging the various roles Hensel fulfilled in life allows one to more fully engage in her art, and to contemplate the whys, wherefores, and hows inherent to her creative process. Thus might one build an understanding, of not only her body of works, but the uniquely creative elements at play within them. Elements of the past (Bach, Beethoven, Schubert), contemporaneous (Schumann, Liszt), and future (Brahms, Liszt) intermingle in some thoughtful ways, and one senses, especially in her later works, a through-compositional style that would’ve found fulsome expression on the opera stage, a medium for which she would have been eminently suited. Soprano Chen Reiss agrees on this point, and brings her own beguiling brand of elegant, operatic flair to a new album. Fanny Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder & Overtures (

Acknowledging the various roles Hensel fulfilled in life allows one to more fully engage in her art, and to contemplate the whys, wherefores, and hows inherent to her creative process. Thus might one build an understanding, of not only her body of works, but the uniquely creative elements at play within them. Elements of the past (Bach, Beethoven, Schubert), contemporaneous (Schumann, Liszt), and future (Brahms, Liszt) intermingle in some thoughtful ways, and one senses, especially in her later works, a through-compositional style that would’ve found fulsome expression on the opera stage, a medium for which she would have been eminently suited. Soprano Chen Reiss agrees on this point, and brings her own beguiling brand of elegant, operatic flair to a new album. Fanny Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder & Overtures (

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.