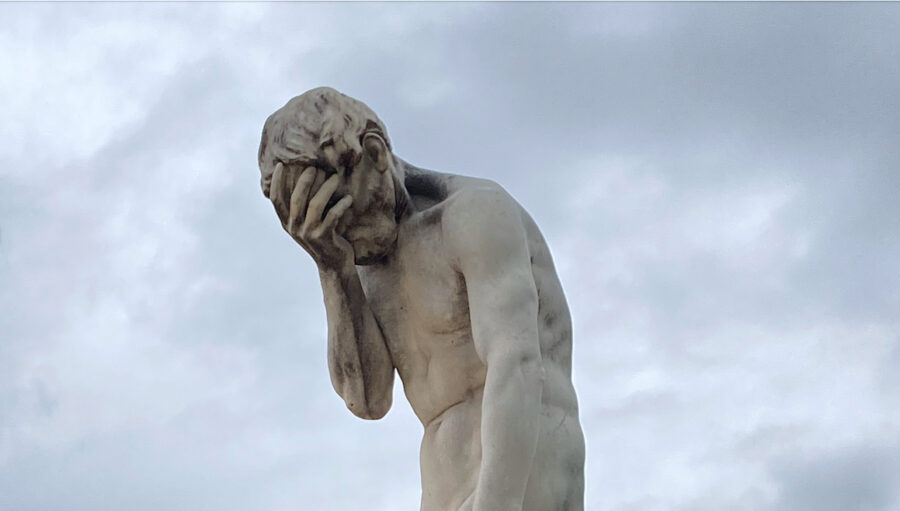

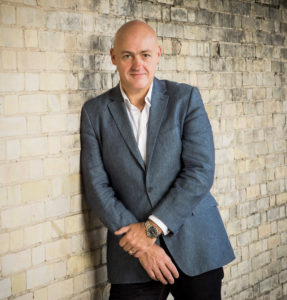

Anyone who has ever seen John Daszak live in performance isn’t likely to forget the experience. The British tenor brings to mind Goethe’s quote that “(g)reat passions are diseases without hope (Große Leidenschaften sind Krankheiten ohne Hoffnung)” (Maxims and Reflections, No. 23). Opera – its artists, its practitioners, its scholars and its fans – are all thusly afflicted, willingly and repeatedly, by the “disease” of opera, that most magical of art forms – one which Daszak so excels in, and indeed largely, boldly embodies.

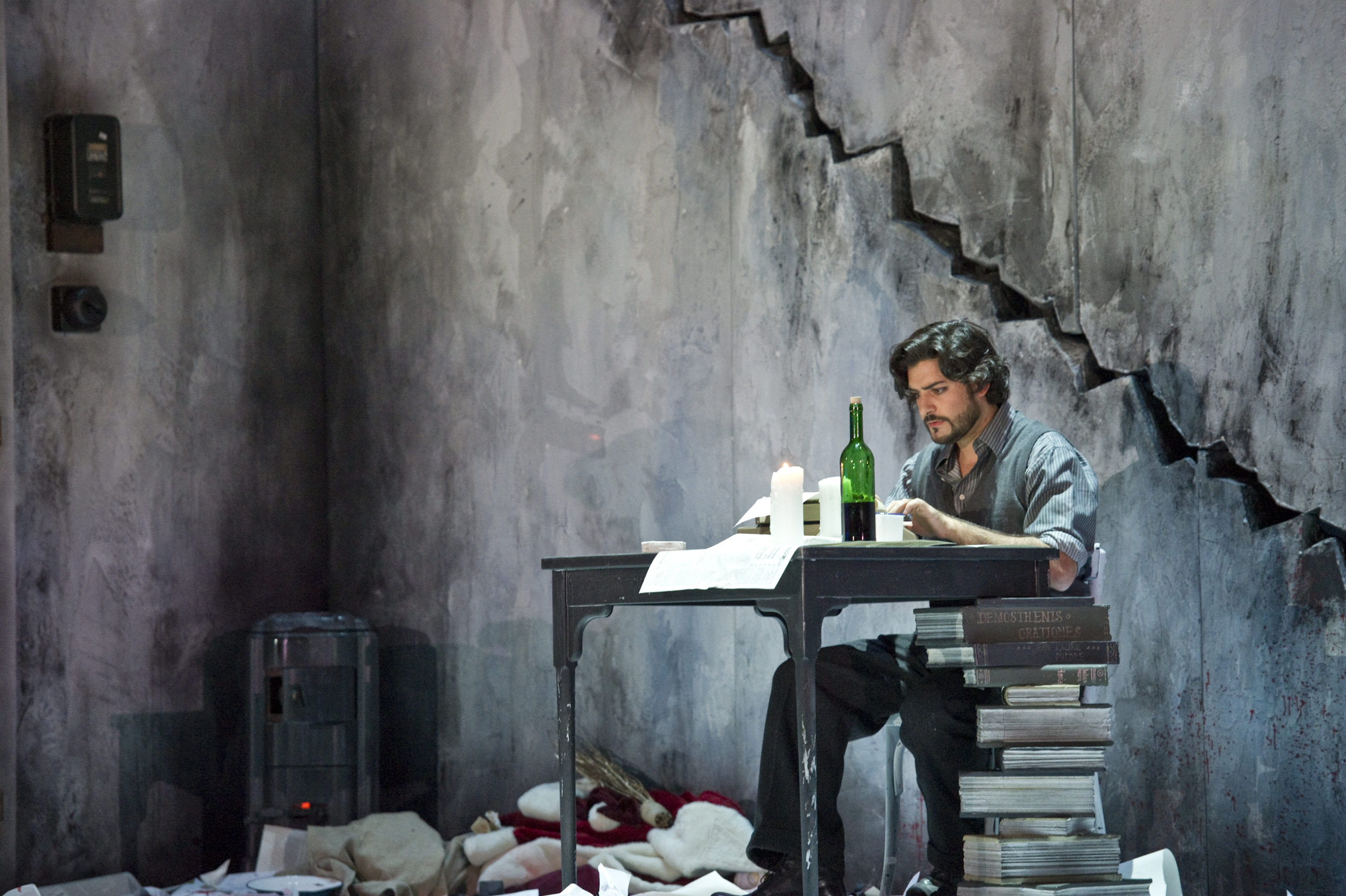

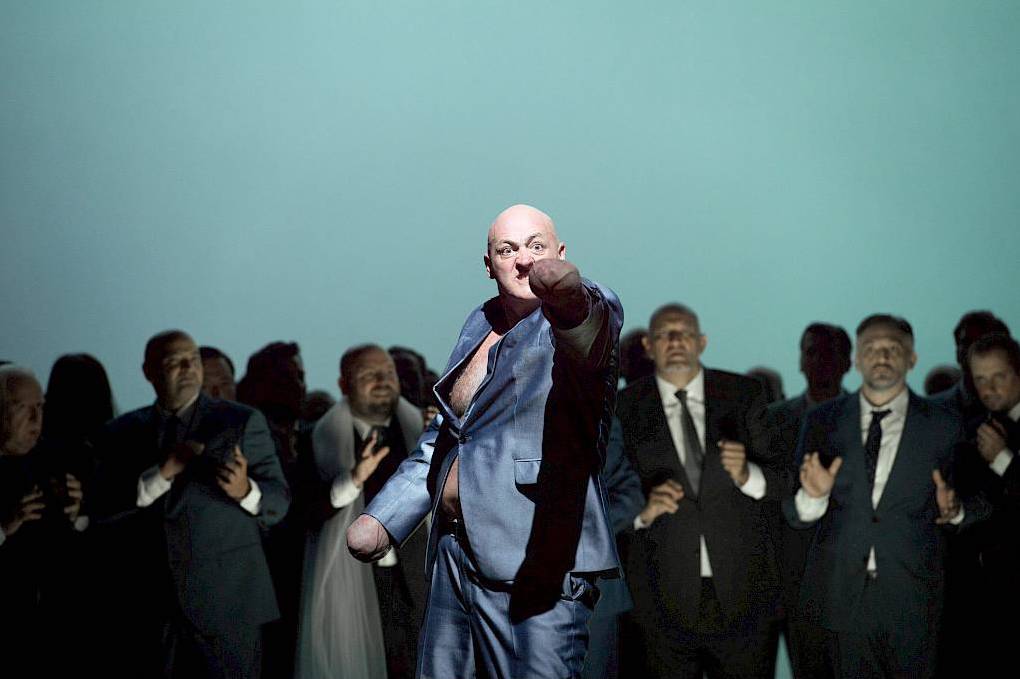

Earlier this year the busy singer performed on the stage of the Bayerische Staatsoper (Bavarian State Opera) in Munich, in a colourful new production of Janáček’s Kat’a Kabanová by Krzysztof Warlikowski with musical direction by Marc Albrecht. Daszak was the hapless husband Tichon, opposite Corinne Winters in the title role and Pavel Černoch as lover Boris; he imbued the character with an unmissable pathos, betraying his own deep and longstanding love of theatre – and then there’s that voice, one capable of both great lyricism and great authority in equal measure. His Tichon, performed with a crystalline Czech diction and agile vocality, had a ringing top and a texture colourful and glowing one moment, despairing and plaintive the next. It was a dramatic if controlled approach, one perfectly befitting the singer’s approach (largely sympathetic, as you’ll read) while also attuned to the composer’s percussive writing. Showman? Definitely, but never just for the sake of it.

Getting his start at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and then the Royal Northern College of Music, Daszak made his debut at the Royal Opera Covent Garden in 1996 and has since gone on to perform at the some of the world’s most acclaimed houses including The Metropolitan Opera, Teatro Alla Scala, Berliner Staatsoper, Komische Oper Berlin, Opéra national de Paris, the aforementioned Royal Opera, The Bolshoi, Dutch National Opera, Teatro di San Carlo, Staatsoper Hamburg, Grand Théâtre de Genève, and Teatro Real; he has also appeared at a variety of annual events including Glyndebourne, Bayreuther Festspiele, Ruhr Triennale, and the Salzburg Festival – where, in 2017, Daszak sang the role of Tambour Major in a critically acclaimed presentation of Wozzeck directed by South African artist William Kentridge. Together with these appearances, he has worked with a range of famed directors (Tcherniakov, Bieito, McVicar, Kosky), and conductors too (Daniel Barenboim, Tugan Sokhiev, Kirill Petrenko, Simone Young) – as he explained in a recent conversation, what’s most important for any and every opera team is an innate appreciation of the art form as both theatre and music, together.

Complementing that appreciation is a broad and largely demanding repertoire, one that reflects both an artistic curiosity and a love of, and for, drama. Throughout his career he has often embodying tormented, slippery, and/or unsavoury characters; Daszak’s characterizations run the gamut from touching to sympathetic to heroic to outright sleazy – but they are always recognizably human. That human quality is especially noticeable in the voice; one is tempted to offer comparisons here (Kollo, Beirer, Vickers especially) – but Daszak is Daszak; the diction is impeccable; the tone, alternatingly sweet and acid, depending on the work; the delivery, keenly aware, attenuated, careful, dazzling. Works by Shostakovich, (Richard) Strauss, Hindemith, Mussorgsky, Britten, Rimsky-Korsakov, Schreker, Pfitzner, Prokofiev, Wagner, Weill, and of course, Janáček pepper his bio; the role of Herodes in Strauss’s Salome, which he’ll be doing again in Zürich shortly, is one could claim to have put his signature on, albeit in wildly different productions, including a memorable presentation by Lydia Steier for Opera national de Paris in 2022.

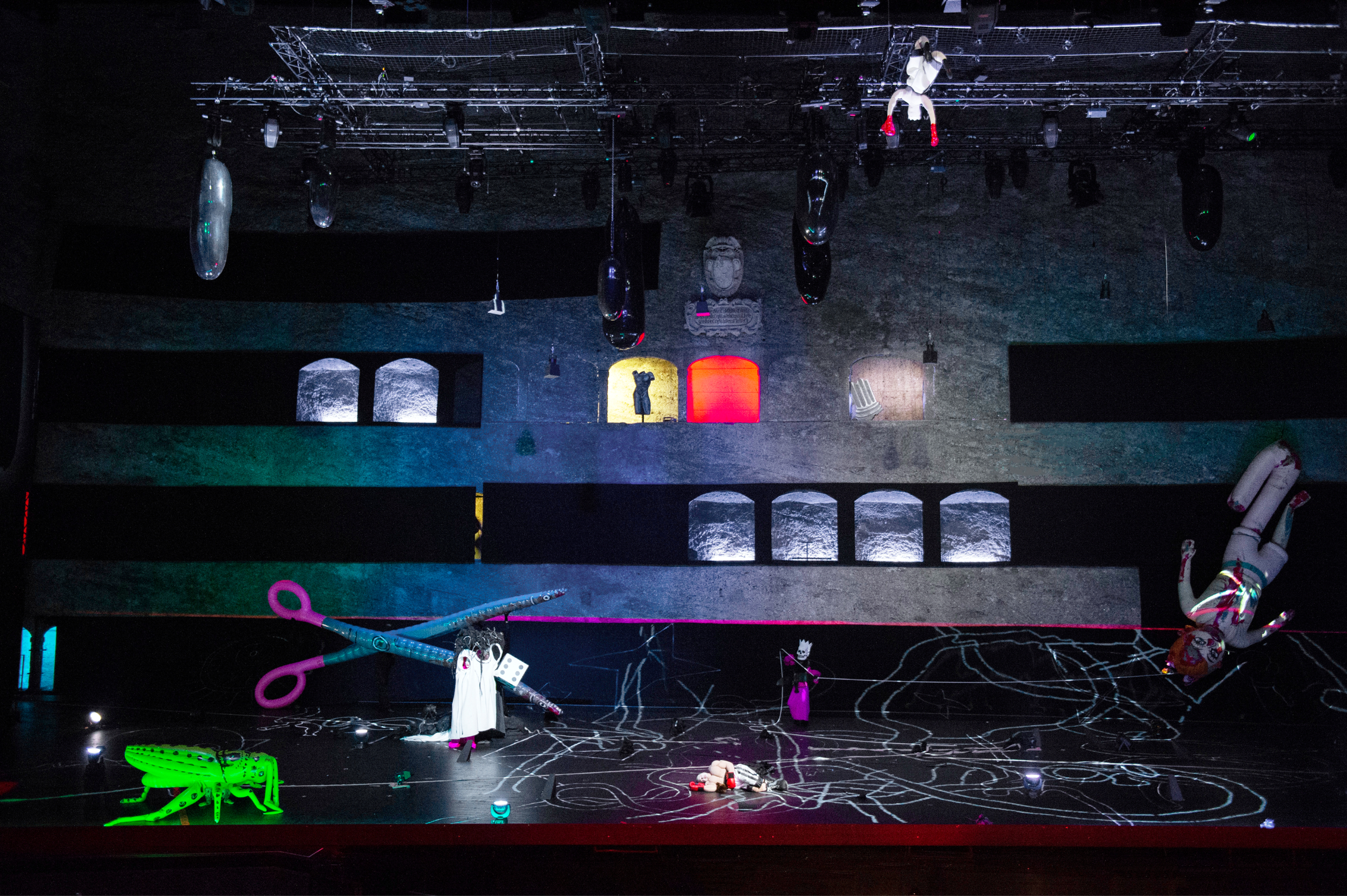

His turn as Tichon in Kat’a Kabanová last month in Munich marks the latest in a long line of appearances at the storied Bayerische Staatsoper, where he has appeared in a dizzying array of roles. Those include the titular Der Zwerg (Zemlinsky); Le Lépreux in Messiaen’s epic Saint François d’Assise; Bernardo Novagerio in Pfitzner’s Palestrina; Die Knusperhexe in Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel; Prince Vasily Golitsïn in Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina; Tambour Major in Wozzeck; Aegisth in Elektra; and Alviano Salvago in Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten. The latter role was one he also performed at Opernhaus Zürich in 2018, in a very memorable (and rather muddy) production directed by Barrie Kosky and led by Vladimir Jurowski. In 2020, he appeared again at the Zürich house as Prince Shuisky in a pandemic-era presentation of Boris Godunov alongside bass Brindley Sherratt.

Passion for the stage and for music connect with passion for his own culture; as much as being an ambassador for opera, Daszak, who has Ukrainian heritage, has also been a vocal supporter of the country and its people, particularly since Russia’s invasion in 2022. That doesn’t mean, however, he won’t appear in Russian-language/penned operas; it does mean no more trips to Moscow. As he explains, it’s a personal decision, one that, in his case, has direct connection to those at the front. Currently in Italy, Daszak is preparing for dual roles (as Il carceriere and Il grande Inquisitore) in Dallapiccola’s Il prigioniero with Teatro dell’Opera di Roma opening 23 April. From Rome, he heads to Zürich for a revival of Salome opening the end of May. He returns to Munich as part of Bayerische Staatsoper’s summer festival presentation of Kat’a Kabanová on 7 July.

Speaking in a rhythmic, rapid-fire blend of memories, musings, and lines from favourite works (operas, novels, poems and pop songs), Daszak is an intense – and intensely likeable – presence: unpretentious, earthy, funny, and roaringly intelligent. Perhaps he is a symbol of Goethe’s “disease” – or rather, quite simply, an embodiment of the art form itself. Either way, if conversation was a song, our recent exchange was an entire cycle, and then some.

Káťa Kabanová: “The whole opera is really about dysfunctional relationships”

L-R (foreground) Corinne Winters as Káťa, Violeta Urmana as Marfa, and John Daszak as Tichon in Bayerische Staatsoper’s new production of Káťa Kabanová, premiered in March 2025. Photo © Geoffroy Schied

Tell me about your first time singing this opera…

It was in 2000, in Paris – I was 32 years old. It’s funny because I work with singers now. I like coaching and online teaching. I’ve got quite a few students now since COVID, because people were locked up and they couldn’t go anywhere and they said, “Do you want to give me a lesson?” I said, “Yeah, sure, because I’m at home, I’ve got time, you’ve got time, why not?” So I worked with these singers, some of them are quite young – 30, 31, 32 – and I thought, good lord, I sang Peter Grimes at La Scala and Boris in Káťa Kabanová at Paris Opera at that age… wow. Before that, I did it when I was at Glyndebourne on tour – I was singing in the chorus and covering Tichon. So I knew the role at that point, but I’d not sung it.

What’s it like coming back to the same opera after two decades, but in a different role?

It’s fun but it’s also strange, because of course I’m no longer the “young lover“; people might not now cast me as Boris, or even Sergei in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which I’ve sung quite a bit. Maybe you could get away with that one, actually – Sergei doesn’t have to be that young – but Boris is supposed to be roughly 20 years old, I think, he even says his uncle’s in charge of his inheritance until he comes of age. But when you’re playing someone who’s not so different in age from you, you see things differently.

John Daszak as Tichon in Kat’a Kabanova at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Geoffroy Schied

And how do you see Tichon?

I feel for him. When I first came into the production, I knew I wanted to play him as a sympathetic character. I think he should be in love with Káťa; people say, “Oh, he’s not in love with her” – I play him as if he is in love with her but he can’t function as a normal human being because of the damage done by his mother. I play it like he’s living under this big shadow of his mother that he can’t really get himself out of or away from – he loves Káťa but he can’t function in a relationship because of the dysfunction within his own upbringing. The whole opera is really about dysfunctional relationships.

Language, Sound, Meaning

To what extent does the language complement that dysfunction?

The language is so percussive and rhythmic; so specific, and very evocative of the people. Janáček’s music reflects the Czech language itself, probably more than any other Czech composer. I think all of the rhythms are in the writing – in the percussion; in the strings; in the woodwinds. You can hear this stress on the first syllable and then there might be a long syllable after. You hear the language right in the music.

You’ve been in Russian, Czech, German operas; what’s your process for learning them?

My operatic career can be likened to this: there are people who like skiing down a beautiful piste and having lunch at a restaurant and a glass of wine and then skiing on, and the people who like to go in a helicopter to the top of a mountain, get dropped off and ski down the mountain. The latter is the kind of opera experience that I am used to. I’m a helicopter skier, not in real life – but in opera, yes. So yes, I have sung Russian in Moscow; Spanish in Madrid; Italian in Italy; of course French in France. And German in Germany, though I still haven’t mastered spoken German. But I don’t think I’m really a natural linguist, and I don’t believe that you have to speak a language fluently to be able to perform an opera in that language – I mean, I don’t speak Russian; I don’t speak Spanish. But what you do have to do is study – and you have to have a thorough process of learning.

My process is, first of all, if someone offers me a new role, I look through all the music and think, “Yep, I could probably manage that.” Then, if I accept it and have to learn it, I go through the whole of the text, and, if it’s tricky music, I mark up different beats here and there – where the stress is in the bar, so I know my way around it to navigate musically.

Then I go through the text, and I work with someone who’s a native speaker in that language. You’ve got to find someone who speaks that language, who’s also preferably got an artistic side, but not necessarily. I work with them for a few hours. It takes at least, I would say two or three sessions, each one consisting of two or three hours, so it’s at least six to nine hours in total to go through all the text and learn how to pronounce it; you need to know the pronunciation of everything. Then comes a literal translation – every single word, what it literally means; it might not make sense in English, but at least you know exactly what you’re singing at what point. For instance, at one point in Jenufa, Steva sings what literally translates as “I, I, I, I drunk?” – it doesn’t make much sense in English, but he’s really saying, “What do you mean I’m drunk? Me? Me drunk?” So you have to do pronunciation, literal translation, and then a kind of cultural translation. But it’s interesting that it’s almost impossible to do justice to Czech in an English translation, because all the stresses are wrong.

“I didn’t think of it as being any different from any other music”

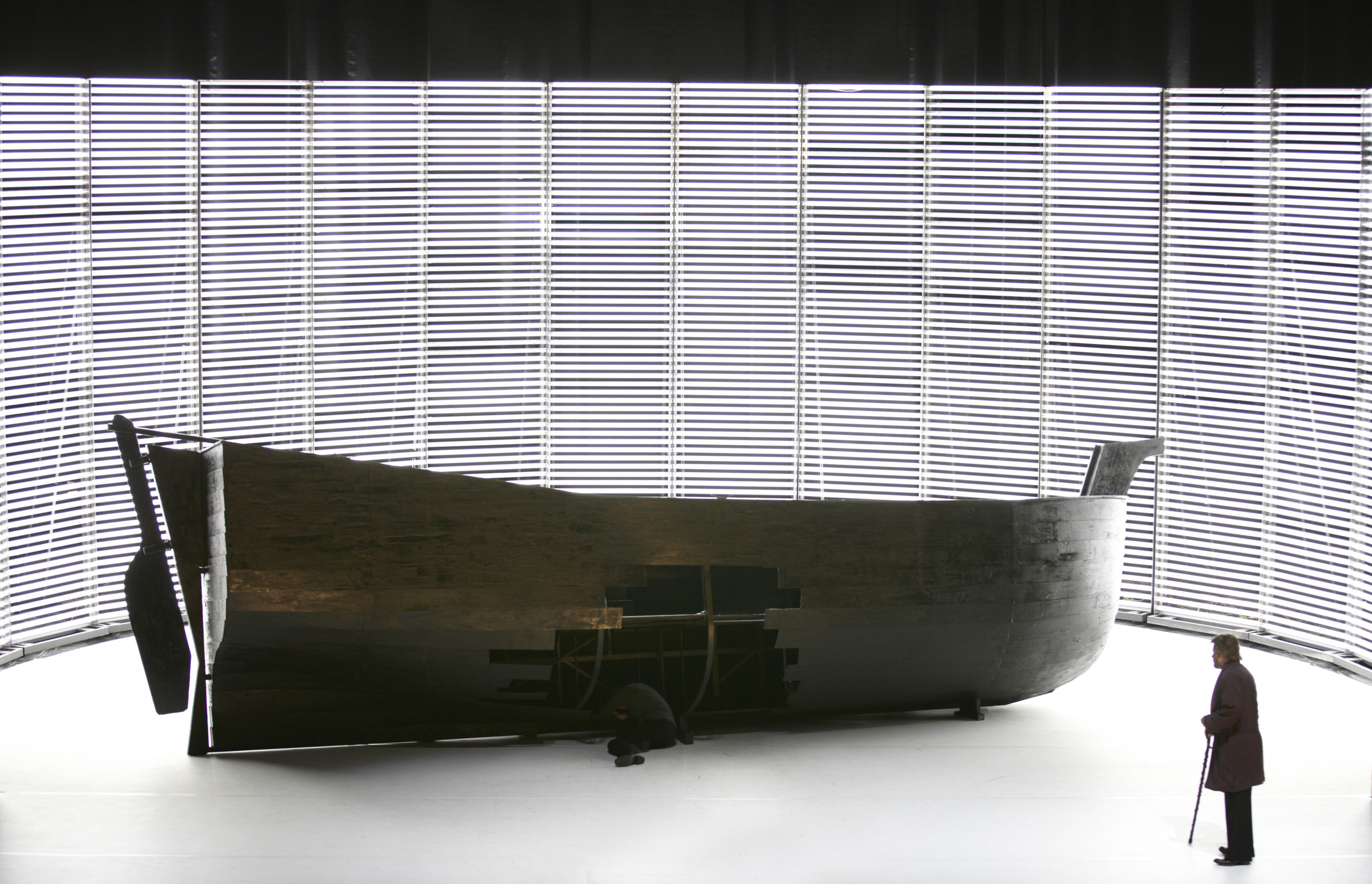

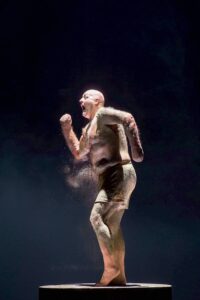

John Daszak as Alviano Salvago in Oper Zürich’s 2018 production of Die Gezeichneten. Photo © Monika Rittershaus

Did you set out to actually do these kinds of roles?

I built my audition repertoire from singing in Glyndebourne Chorus – it was a great place to get a bit of training; if you’re in the chorus they try to find decent covers from the chorus. So if someone gets sick you go on and do rehearsals, or you go on and do a show. I’d been studying there and learning Tichon and Steva.

So you already knew that this Czech music was in your voice…

… because I’d been asked to cover them. I auditioned and they immediately said, “Oh wow, you can cover some of the Janáček pieces.” It was the then-casting director, Sarah Playfair, who picked up on it at the time.

Had you ever considered Janáček before that?

Funnily enough, one of the operas we did at the Royal Northern College of Music was From The House of the Dead. I sang Skuratov, which is quite a big role, and it was great fun. I didn’t think of it as being any different from any other music that I sang at the time, but I was probably 22 years old. I think the music was somehow in my heart and blood, maybe because my dad is from Ukraine. I feel like I know these Janáček characters, because I’ve grown up with my father around the house, and around his friends. Even though there weren’t that many Ukrainians in the UK, there was actually a Ukrainian club in our local town outside Manchester and there were quite a lot of expats at that club who’d left during the war.

Do you have any problem with performing Russian works now?

I talked with a Ukrainian lady who’s a journalist just the other day and she asked the same thing. My cousin’s son is a viola player and he’s now in the army at the front. People might well say, “Well, then how can you appear in Russian works knowing that this is happening?” I can understand it, but also, if it’s not a contemporary work, then what did Tchaikovsky have to do with what’s happening now? Also most Russian historical composers were anti- establishment – think of Shostakovich: in Lady Macbeth he’s taking the mickey out of the whole government, he’s making them look foolish. That’s why Stalin, when he saw it, said “Nyet”. I think it’s a mistake to cancel everything. Certain performers who haven’t clearly said “I’m against this” I have more of a difficulty with.

I had a contract in Russia myself – I was supposed to go back and do a Salome there that we’d done in Aix-en-Provence but thank God it was cancelled. I don’t want to go there. I can’t imagine that I will ever go to Russia again – it would take a long time and there would have to be a lot of positive things done towards Ukraine before I would do it. As it is, I haven’t even been to Ukraine during the war. I was asked if I would go to adjudicate a competition; I spoke to my family about it, and they said, are you insane? I wanted to show solidarity with my family and Ukrainians at this terrible time, but my cousin’s son said “No, you’re better staying out of Ukraine; you can do more for Ukraine in what you’re doing right now than you could by coming here.”

Violeta Urmana as Marfa and John Daszak as Tichon in Kat’a Kabanova at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Geoffroy Schied

Blending Singing and Theatre

How do you balance music and theatrical elements?

From as far as I can remember from being a child I was always a bit of a showman. If I saw an advert on TV, I’d reenact it for my parents and my two older brothers – I think it’s to do with being the youngest: you’re always striving for attention. I’ve always been kind of theatrical. I started singing very young and I used to sing a lot and was in choirs, though I did play violin and then switched to double bass. I had a theatrical side to me, but I didn’t have the technique of acting; I knew nothing about it. At the RNCM (Royal Northern College of Music) I remember being around the Head of Vocal Studies, the singing department of the Opera School, Joseph Ward, who had a great voice, very English. He was a tenor and he had this heady, warm sound; equally important was how he made you respect what you were doing, including most especially the acting side of things.

If I did a lieder recital now, I’d have to almost stage it – I’ve always been busy with opera and that is my favorite thing, to have the costume, set, rehearsals, the theater side of it, because for me it’s kind of escapist – but if you’re doing a lieder recital in front of an audience, you can really see the faces of the audience, all looking at you; that’s one of the scariest things in the world. I have worked with Julius Drake for many years, and I remember over 20 years ago he wanted to do The Diary of One Who Disappeared at the Chichester Festival, and of course, I’d sung in Czech already. I memorized it and made it into a bit of a show. I used a chair and some props – everybody loved it. It was very successful.

John Daszak as Alviano Salvago in Oper Zürich’s 2018 production of Die Gezeichneten. Photo © Monika Rittershaus

What’s your relationship with directors?

I’ve worked with a lot of great directors, including a lot of cutting-edge ones like Bieito, Tcherniakov, Kosky, Warlikowski. They’ve repeatedly asked me to do things with them because they like the way I work. I always see it as my responsibility: to try and do the best job for the music and the text. That means I try and do what the conductor wants, and try and do what the director wants. I don’t think I’ve ever had such a big issue with a director that I’ve said, “I can’t do that because I’ve got to sing” or “I’m not going to do that because that will make me look ridiculous.”

Die Gezeichneten in Zürich was incredibly daring. Can you imagine the conversation at the beginning with Barrie? “You’re gonna strip off and have mud and blood thrown at you.” We actually had a rehearsal just for the mud and blood part! I came in one day and there was plastic all over the floor, and I thought, “Yep, here we go!” Kosky is great because he enjoys working and you always have fun with him in rehearsals, but also he’s got a brilliant mind; he remembers everything, and if you mess something up or don’t remember what you did gesture-wise, he’s on you straight away: “Ah, no, you’re supposed to do that.”

Tcherniakov is also fantastic – he wants things to be very specific; he’s almost got a kind of cinematographic idea of exactly what he wants but he does say, “No, don’t do that, do it more like this” or “Great, I love what you did; do it again.” There’s a framework. Warlikowski is less structured, but he is fascinating to work with; we sit down and talk through the text. There is an overall concept, but it’s much more like, ‘We’re going to discover things on this journey together.” There’s a lot of experimentation.

And conductors?

They tend to have a very specific idea of what they want – sometimes it does become a problem if they’re not so interested in the dramatic side. Zubin Mehta is, for me, still one of the best opera conductors, because he’s so with you on stage. He was always controlling the orchestra, and looking at you; if you held a note a bit longer, then he would wait. He has the technique to do that, and he also has an interest in what’s going on on stage. He understands it’s about the singers and about the drama, about the theater. So the best opera conductors understand and like both things: the music, and the theatre.