Photo © Gaetz Photography

Update 22 June 2020: The Canadian Opera Company has cancelled its 2020 autumn season. The conversation with COC General Director Alexander Neef, below, took place in May 2020, prior to the official announcement.

Cancellation, closure, calibration: these are the elements at work within an arts industry trying desperately to stay afloat in the middle of a pandemic. What to cancel? What to postpone? What to calibrate – or recalibrate – as the situation warrants? Which companies will be around in year, and which will close? Some organizations are busily preparing for presentations of old favorites within the context of a new normal dictated by the coronavirus, acting, consciously or not, as beacons of an industry facing an immense and undeniable transformation.

The annual Salzburg Festival, for instance, will be going forwards in a modified form as of August 1st. On the slate is Elektra (with Aušrine Stundyte in the lead and Franz Welser-Möst on the podium, in a production by Krzysztof Warlikowski) and a revival of Così fan tutte, as well as four theatre works (including the world premiere of Zdeněk Adamec by Peter Handke) and numerous concerts, including a Beethoven cycle by pianist Igor Levit. In Germany, Deutsche Oper Berlin (DOB) has also made adjustments. The company recently announced a 90-minute chamber presentation of Das Rheingold in its very own car park, running for five performances starting this Friday (12 June), and featuring twenty-two musicians and twelve singers. The production, by Jonathan Dove (who also did orchestration) and director Graham Vick for the Birmingham Opera Company, is not the first presentation by DOB in such an environment; in 2014 the company presented Iannis Xenakis’ Oresteia in the very same parking deck. Wagner’s first opera in his epic Ring Cycle had been originally planned as a fully staged work from director Stefan Herheim, a premiere which has since been postponed. The upcoming version, adhering to the guidelines set out by the Senate of Berlin, has a €5 entry fee and a pay-what-you-can structure, with audience member contact information being recorded and a 1.5 metre distance enforced; moreover, masks will be required when entering and exiting, toilets will be accessible, and (rather crucially) small bottles of “beverages” will be made available to visitors.

Such an ambitious undertaking underlines the very thin lines that currently exist between possibilities and probabilities. Those who can are doing their best, in the most creative and safe methods presently allowable; others are bending and flexing in ways heretofore unimaginable six months ago. The Metropolitan Opera cancelled its autumn season and will be reopening (ostensibly) on December 31st, although it continues to offer a revolving slate of productions online. Looking over their latest release, it’s hard to not think of the artists who were set to make their debuts at the house this autumn, either in a role or with the company itself: soprano Christine Goerke was set to sing her first fully-staged Isolde in a revival of Marius Treliński’s production of Tristan und Isolde; 74-year-old conductor Michail Jurowski was to have made his Met Opera debut leading Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel. On the other side of the ocean, the Royal Opera House, itself in dire straits, is getting set to launch a new series, Live From Covent Garden, on Saturday (June 13), which will complement its extant online offerings of opera and ballet. Curated by Sir Antonio Pappano, Music Director of The Royal Opera, Oliver Mears, Director of Opera, and Kevin O’Hare, Director of The Royal Ballet, the event (set to be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on June 15th) will feature performances by baritone Gerald Finley, tenor Toby Spence, soprano Louise Alder, and the premiere of a new ballet choreographed by Royal Ballet Resident Choreographer Wayne McGregor. The following two presentations of the program, on the 20th and 27th of June respectively, will be available on a pay-per-view basis. Like every company, a prominent “Donate Now” button is displayed on the ROH homepage, one whose request will no doubt grow in urgency as the autumn season inches ever closer.

Rosario La Spina as Radames (background) and Sondra Radvanovsky (foreground) as Aida in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Aida, 2010. Photo: Michael Cooper

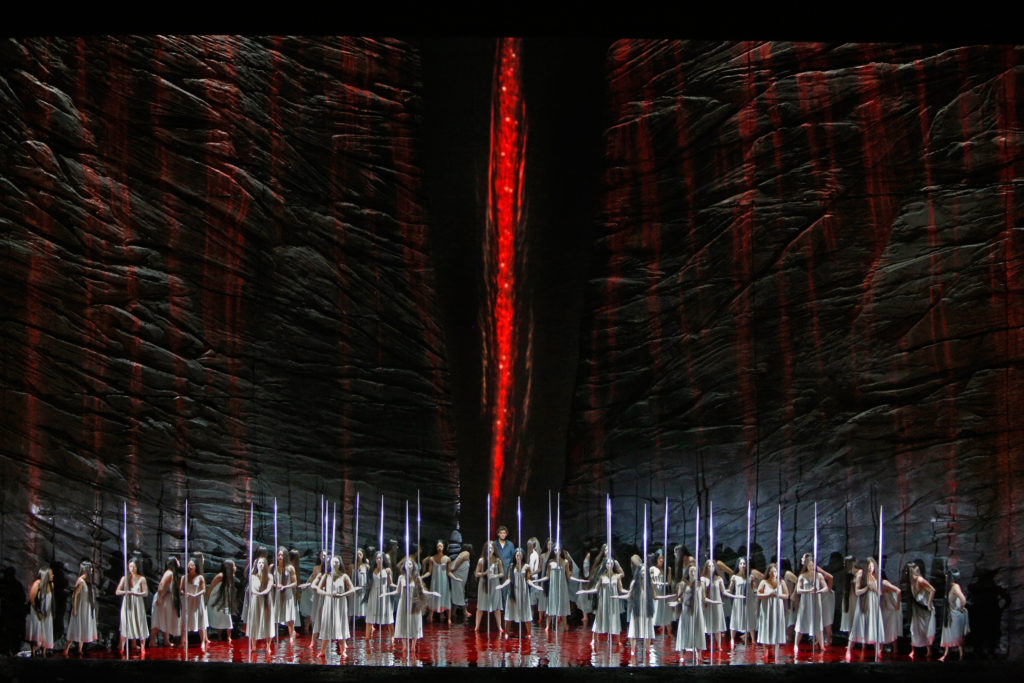

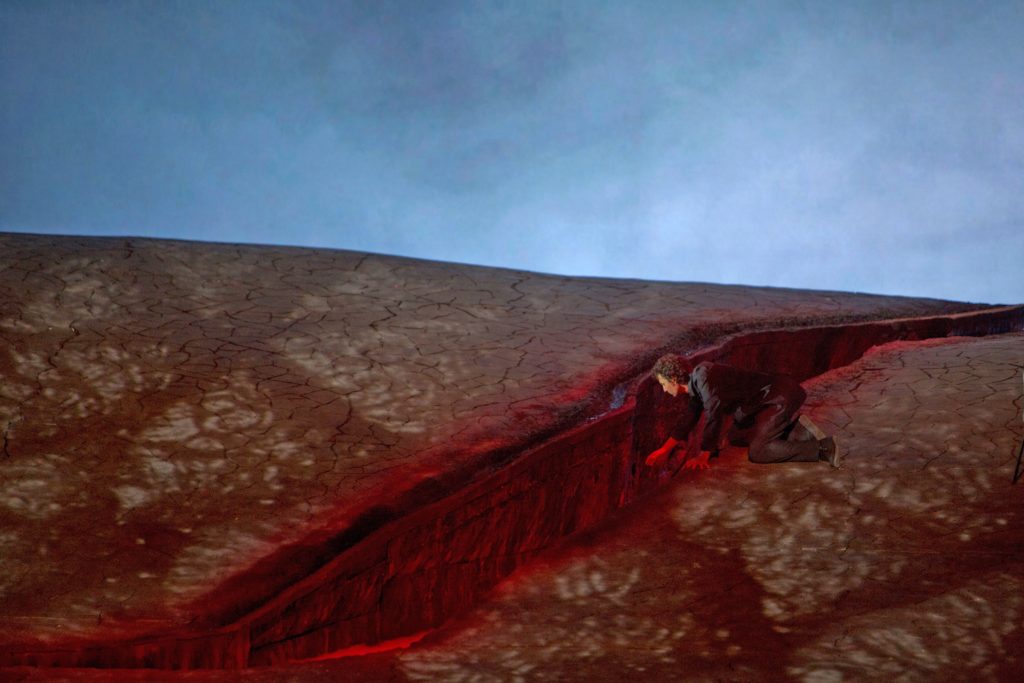

For Canadian Opera Company (COC) audiences, the fall season is just as fraught with uncertainty. In late March the company made the difficult if necessary decision to cancel the remainder of its 2019-2020 season, which was to include revivals of The Flying Dutchman and a wildly divisive staging of Aida by Tim Albery. Bereft of the gilded visuals so frequently attached to presentations of the famed Verdi work, the production had been anticipated for the reactions it might have provoked a full decade after its premiere. Would Toronto audiences have grown to accept Albery’s arresting vision? Would it have been so upsetting in 2020? Will it even be staged again, now that COVID seems, for some, to have put a damper on even perceivably risque productions and programming? The opportunity to discover the elasticity of the COC audience was, alas, lost this spring but another chance, possibly, awaits in the fall. The company is set to present Wagner’s Parsifal – the first presentation of the opera in the COC’s history. A co-production with Opéra de Lyon, The Metropolitan Opera, and the COC, the highly abstract (and at times, very bloody) François Girard-helmed work was presented in February 2013 at The Met, to widespread acclaim. Owing to the monumental nature of the production, the company launched a fundraising campaign with various levels of support named after elements of the opera. Tenors Christopher Ventris and Viktor Antipenko share the title role in the COC production, with Johan Reuter as Amfortas, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner as Kundry, and Robert Pomakov as Klingsor; COC Music Director Johannes Debus conducts. Opening night is scheduled for September 25th.

A scene from The Metropolitan Opera’s production of Parsifal, 2013. Photo: Ken Howard

According to Canadian Opera Company General Director Alexander Neef, those plans are still intact. Neef, who is also Artistic Director of the Santa Fe Festival, had been set to leave the COC at the end of the 2020-2021 season and become General Director of the Opéra national de Paris. The company is facing €40 million in losses this year alone, from both the pandemic as well as numerous strikes which occurred before the lockdown. The Opéra’s current Director, Stéphane Lissner, announced in an interview with Le Monde on June 11th, 2020 that he’s ending his mandate at the end of 2020, emphasizing the extreme nature of the situation brought on by the coronavirus pandemic: “nous ne sommes pas dans une situation de passation normale.” (“we are not in a normal handover situation.”) Neef confirmed in a COC release the following day that he “certainly did not anticipate Lissner’s early departure and that also confirmed not leaving Canada just yet. Neef says he “has not yet had any formal discussions – either with the Paris Opera or members of our Board of Directors – about accelerating the start of my engagement in Paris. Moreover, the ongoing global health crisis makes it difficult to envision how any significant changes to the intended timeline could be accommodated.”

Back in May, Lissner spoke to the unfeasible economics around presenting opera at the Garnier and Bastille theatres within prescribed social distancing mandates. France, like most other locales, requires audience members to be two meters (6.5 feet) apart. “Le protocole [proposé pour reprendre les spectacles] est impraticable : impraticable pour le public, pour les artistes et pour les salariés. Suppression des entractes, c’est impossible, faire entrer 2700 personnes en respectant les distances, c’est impossible, la distance dans l’orchestre, dans les chœurs, c’est impossible,” he noted in early May (“The protocol [proposed to take over the shows] is impractical: impractical for the public, for the artists and for the employees. Eliminating intermissions is impossible, bringing in 2700 people while respecting distances is impossible, the distance in the orchestra, in the choirs, is impossible.”). Will there even be a 2020-2021 season for Opéra national de Paris? The report in Le Monde indicates, if not an outright cancellation, then a greatly altered one, with an emphasis on revivals, including La traviata (led by James Gaffigan, in a production by Simone Stone), the ballet La Bayadère, and the ever-popular Carmen, with Domingo Hindoyan on the podium, in an acclaimed staging by Calixto Bieito. The Bastille is not set to reopen until November 24th, and the Garnier in late December. A planned new Ring Cycle staging is off the books. “Fin 2020, il est probable que l’Opéra de Paris n’aura plus de fonds de roulement” (By the end of 2020, it is likely that the Paris Opera will no longer have working capital”), Lissner told Le Monde. “C’est pourquoi, à partir de janvier 2021, j’ai choisi de m’effacer afin qu’il n’y ait plus qu’un seul patron à bord.” (“That’s why, from January 2021, I chose to step aside so that there would only be one boss on board.”)

The interior of the Palais Garnier. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

That “seul patron” is shouldering a lot of responsibility right now. Notwithstanding this unfolding and weighty situation, plus the cancellation of the COC’s spring season and the uncertainty of its 2020-2021 season, Neef was also very recently heavily involved in negotiations to obtain recorded COC performances for online broadcast during the quarantine – hardly a simple task, as music writer Lydia Perovic ably outlined in her smart investigation into the paucity of online Canadian opera content for Opera Canada magazine in 2018. Yet in our conversation last month, before the Paris news, Neef was his characteristically cool, unflappable self. The COC head honcho and I have spoken many times over the years, most recently last summer following the announcement of his Paris appointment. The German-born Neef has always been direct if highly diplomatic, eloquent but possessing an undeniable edge of steel. With an encyclopaedic knowledge of history (not surprising, given he graduated from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen with a Master of Arts in Latin Philology and Modern History) and a solid if wholly unsurprising knack for thoughtful casting (honed during his time as casting director at the Paris Opera from 2004 to 2008), Neef is as much passionate as level-headed; that passion shows itself in strong, well-observed opinions and observations, and then translates itself into elegantly understated wisdom. Having started at the Salzburg Festival with famed opera administrator Gerard Mortier, Neef went on to work at the Ruhrtriennale, New York City Opera, and later, Opéra nationale de Paris, before arriving in Toronto in 2008. In the decade-plus of his directorship with the COC, Neef has brought a number of celebrated international opera figures to the Four Seasons Centre stage: singers (Ferruccio Furlanetto, Anita Rachvellishvilli, Patricia Racette, Stefan Vinke, Luca Pisaroni, conductors (Carlo Rizzi, Speranza Scapucci, Paolo Carignani, Harry Bicket, Patrick Lange), directors (Peter Sellars, Dmitri Tcherniakov, Claus Guth, Robert Wilson, Spanish theatre collective Els Comediants). He has consistently championed the work of tenor Russell Thomas, who has appeared on multiple occasions on the stage of the Four Seasons Centre (The Tales of Hoffman in 2012, Carmen in 2016 Norma in 2016, Otello in 2019, and was to have performed in Aida this spring), along with that of soprano Sondra Radvanovsky (two operas in Donizetti’s Tudor trilogy as well as Norma), bass baritone Gerald Finley (Falstaff, 2014, Otello, 2019) and soprano Christine Goerke, whose Brunnhilde in the company’s year-by-year presentations unfolding Wagner’s Ring Cycle won her acclaim and, like Radvanovsky, Finley, and Thomas, bolstered a fierce following.

In mid-May, Neef took part in an online chat hosted by the Toronto-based International Resource Centre for the Performing Arts (IRCPA) in which he was asked about how he perceived the coronavirus pandemic was affecting the opera community, singers in particular; I was keen to hear more from Neef and was grateful when, not a week later, he and I had a lengthy discussion – about pandemic, Parsifal, Paris, and, to start, the question of risk and its place in the industry moving forwards.

Photo © Gaetz Photography

In light of the damage the pandemic is doing in the arts world, some believe that opera programming and presentation will become more conservative, that any perceived risk in either is off the table for the foreseeable future. What’s your take – can opera afford to break eggs in a pandemic/post-pandemic environment?

To stick with your analogy: I think there is no art if you don’t break the eggs. And I think since we don’t have any live art in our lives right now, breaking eggs becomes even more important in the future. I got this really interesting manifesto in my mailbox this morning – and it’s easier to say this when you run a little company rather than when you have X number of employees you want to keep feeding – but, it says, “time to commission new works from young composers; time to ally with other theatre, cinema, dance, performing arts centres; time to follow the example of cinema, the storytelling medium that came after opera and was predicted by great opera composers” and so on. When you’re a small, flexible structure, then yes, those boats are easy to turn around; you can be much more reactive. The bigger your apparatus becomes, the harder it is to change because there are a lot of people who need to make that change with you, but in general, I’ve never believed and still don’t believe it, that going back to more traditional approaches, to what we consider “safe” repertoire, will do anything for the future sector – the only thing it will do is make people get more tired of you. Or, to say it another way, how many times will you need to see the same production of La bohème, even though it might be with different people? At some point you may say, “I’ve seen this five times over the last ten years; give me one reason why I should go again?” I think what we’ve been trying to do is to space things out enough, or to hold off with programming, so there’s still for us a reason to do (a certain opera), other than the reason that it’s popular repertoire…

Or it’s nostalgia…

… or it’s nostalgia, yes. Also, our audience is not eternal. Like everybody who deals with an audience, we are always interested in refreshing – we want a relationship with our public where we don’t always confirm what they think opera is.

That’s a big hurdle, especially for companies who play into clichés. How do you counter it?

It is a hurdle, but I continue to believe, and this crisis hasn’t changed my opinion so far, that what’s really important is people know what kind of company they’re coming to; you need to have a spine. And again, I always say, and have said: indifference is our biggest enemy. If people think, “Oh, this is the same old thing” or they leave a show and can’t remember, ten minutes later, what it was all about… well, obviously we want people to like what we do, but I prefer they hate (a production) with a passion than be indifferent to it. Unfortunately we didn’t get to do that revival of Aida that people were itching to see, for very different reasons!

I distinctly recall someone saying to me at the opening in 2010 that “it’s actually just fine if you close your eyes.”

Think what you want about that production but ten years later people still talk about it. That’s what I mean when I say indifference is our biggest enemy. Obviously there was a lot of rejection at the time but also a lot of people came to it and said, “Wow, I had no clue opera could be so current, and about me, and not just stuffy and purely representational.”

There were also younger people I know who went and later said, “That was my first opera experience and I wanted grandeur and camels!”

… and other people walked away from it thinking, “Where has this art form been all my life?!” So it’s hard to say what’s interesting to one and not to the other. People think about young audiences that, very often, those are the ones who want the avant-garde, but I think it’s not necessarily true; sometimes they’re way more conservative than someone who’s been subscribing for twenty-five years. It’s a complicated thing! But just because you are older does not mean your taste in art is more conservative – that’s not how it works.

Jonas Kaufmann as Parsifal in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Parsifal, 2013. Photo: Ken Howard

There’s been so much effort on the part of classical organizations to try and get this mythical young audience, but I feel as if the pandemic has forced them to realize the importance of a far wider cultivation.

In the end you can’t afford to ignore any part of your audience. Right now there’s an issue with at-risk populations; a young audience is not seen as so much at-risk (for COVID), but I think that shouldn’t mean we totally abandon our older audiences. The whole discussion for me is kind of moot anyway, because you cannot separate the discussion of keeping an audience safe from keeping the performers and staff safe, and while that might not be exactly the precisely same measures, if you can’t combine both, then it’s going to be very hard to have a show. Right now the pit is a very dangerous work environment. We’re in a lucky position in Canada and the COC – we won’t be going back into rehearsals before two-and-a-half months from now, so we will have better information in two weeks, four weeks, six weeks, that will allow us to make better decisions. The big hiatus we have now, I’m rather grateful for that.

Some in the Toronto opera world are wondering what will happen to Parsifal – it’s been a long road to having it staged at the Four Seasons Centre.

What I say is: I simply don’t want to make that decision right now. And I don’t feel I have to. Right now we’re living in an equation with too many variables and those variables make it hard to solve that equation. There’s already some measures falling in place in terms of public health advisories, and some of the variables are starting to be eliminated. Today I read something stating that essentially the virus is mostly circulating in the GTA (Greater Toronto Area) and the rest of Ontario is under control – which is not great news for the GTA, but it’s true in all urban centres – Montréal, Paris, all those places – it’s true that it hangs on (in those locales) for longer because there’s more movement of people, but it also means it can get contained. We need to have a better idea of the public health measures.

Obviously we won’t be able to perform Parsifal if we have to have limited numbers in the audience, it’s an economic nightmare and it wouldn’t be worth it. We couldn’t even accommodate all of our subscribers (in that scenario), but we have to be prepared, and we are taking the time to be prepared, and when we have to make a decision, we will gather all the elements to make the best decision for our staff and performers, and the house, and everyone.

The interior of Palais Garnier. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

It’s a strange new equation to accept, that we are now in a world where there’s a question mark over both Parsifal and Paris’s opera season.

It is a strange new equation, and with strange new variables – and I think one needs to take this a week at a time. There are supposed to be additional announcements of openings in Europe…

… under strict conditions. Returning to the theatre-going experience people are familiar with will take much longer.

Yes, and it’s a two-way street, or more than a two-way street. A part of it is medical progress as well – I think even more effective and widely-available testing will do a lot to reassure the public about the situation. That is big! Everybody knows the vaccine will take a little while but also we’re working on all kinds of things in terms of an effective antiviral, because the truth is, if we didn’t have a flu vaccine we would be having a terrible situation every winter. But because we have a flu vaccine there’s no discussions of masks or additional hygiene measures during flu season… so we need to find a way through additional safety measures, through progress in medicine, all of that, to kind of normalize this situation in a way that is… I mean, there’s always a risk: you leave your house and you can catch something on the subway, right? That happens to a lot of people. I am not a scientist and indeed COVID is very contagious – if you get sick you can get very sick, but we need to take time to really learn more about it and then calibrate all the available information and input it back into a form where people can gain a certain amount of comfort in leaving their homes, in order to assess different levels of risk.

View from the orchestra pit of R. Fraser Elliott Hall at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. Photo: Lucia Graca

How do you see the current recalibrating in the opera world influencing not only companies but artists?

Again, for everything that’s on the performer’s side, regular testing is going to be the key so that you can be certain the people working together in confined spaces, people touching each other in rehearsals and so on, they can have a reasonable level of confidence that everybody is up to date on their health. Now it’s the case that you wake up in the morning and you feel a little bit off and take your temperature; three months ago you would have thought, “Oh I’ll see how I feel in the afternoon” but today you get the thermometer out and look at the reading and say, “It’s not normal.” People will be more sensitive to their own symptoms and more responsible, I think. I was reading something interesting, about how work culture will change, especially in North America, where coming to work sick was like a badge of honor, not letting the company down, now it’s, “You’re not feeling well, we don’t want to see you” and that’s not necessarily a bad thing! That’s the performer’s side.

On the audience side, if people feel safe again if wearing a gloves and a mask when they go somewhere and feel okay to sit next to someone they don’t know, if we can reach that level of confidence, I think nobody will care about people wearing a mask in the foreseeable future in a theatre, even if it’s not a requirement. It will be part of the new normal, and frankly, it’s normal already in certain parts of the world. It’s funny that in Canada, which was so haunted by SARS, mask-wearing didn’t become a norm, so maybe now it will. If that’s the worst thing that can happen to us, that people put on a mask before walking into the Four Seasons Centre, we can do that. There’s so much cultural change about masks that’s already happened – people felt, “Oh you can’t speak with a mask” – well, people do it all the time. I was at the supermarket the other day and ran into someone I know, and we didn’t take our masks off, we just spoke with our masks on at a safe distance. Places are going to normalize these kinds of protocols, and it’ll make it all less scary, I believe. And of course, if you are part of a risk group, you would think twice about where you go and what you do; we might be able to accommodate you somewhere in the theatre. We’re more than happy to do that with patrons; it’s our business to accommodate their needs. Frankly, every theatre would be willing to do that to get their patrons back. But then again it’s not something we haven’t done already in making all reasonable accommodations for people with needs.

Tenor Russell Thomas in rehearsal for the Canadian Opera Company’s production of Otello, 2019. Photo: Canadian Opera Company

And casting?

That’s actually one of the bigger problems we’re discussing. Zoom doesn’t give you a lot of information about the size of the voice but it does give you information about the personality you’re dealing with, about pitch, about rhythm. We were talking about this in relation to the ensemble, for example; they were Zoom coaching before they went off contract for the summer. Everybody hated the idea initially, and then came away saying it was better than not doing anything at all, so that is obviously also a part of that new normal, as you say. There’s also the situation of stage auditions and having a pianist and nobody in the hall except for two or three casting people; that seems less complicated than a full stage performance in this environment, if you can get them safely in through the stage door and onstage. All these things are being worked out.

I’m curious if you think digital platforms like Instagram will become a big factor in casting the post-coronavirus opera world.

It probably will… but… I look at it more as an added tool to what we’re already doing than anything else. We have more and more tools at our disposable, yes, but there’s a lot of the old stuff that still works and we can’t abandon it, that’s been true for our marketing and communications as much as for casting – we still send postcards to people (for marketing) because there’s people who really like postcards, maybe not as many as twenty years ago, but it’s still a valuable part of our audience, so why would we abandon that practise?

Alexander Neef at the COC’s 2020-2021 Season Reveal event, 2020. Photo © Gaetz Photography

So the same holds true for singers then? I see a lot of imitation online.

As I said in the IRCPA talk, people who do casting are really not very interested in generic products…

… you mean in terms of singers pushing an homogenous image?

Yes – going back to your breaking-the-eggs metaphor at the beginning of our conversation, if you don’t have that appetite for risk-taking there’s not going to be a lot of art in what you do.

Strange to think that being yourself is perceived as a risk.

We all know it’s the hardest to be yourself – but as an artist you have the opportunity to not be yourself, and to figure that out, and to live it out, in a way a lot of people cannot, but I think it’s very important to have that self-assessment skill and to figure out, clearly, “What can I do better than other people?” If you have better high Fs than anybody, then all I want to know is, can you sing Queen Of The Night? That’s the thing, and there’s nothing bad about it, and you must acknowledge that as you get older, your high Fs won’t be as great, and you’d better figure out what you can do then.

Or have figured it out already…

Yes. It comes back to having a lot of courage. Sometimes I feel the courage, especially for a young artist, will always come before the self-assurance, but it’s kind of a bit of – I really like this egg thing you started with! – it’s a chicken-and-egg situation: if you don’t put in the courage it might just never happen, but you will not know if there’s a reward before you’ve done it, and I think doing it for the first time, and seeing if it works, will give you more courage for the second time, and so on.

The benefit of digital is it’s creating a vital form of community a lot of people miss right now – are the recent COC opera broadcasts a sign of things to come?

Right now it’s a concession to the times we’re in; we wouldn’t want to necessarily put archival recordings out as a standard, but what’s important for me is – and some don’t see it this way but that’s fine – that it’s about creating a presence for all those artists who can’t work right now. Putting this kind of work out – work that was done in a good environment, where (artists) are performing good roles with a good company, with a high level of quality – reminds the world that is what artists do. And having such material released also reminds the world that this is just a video, and if you want the real thing, you will have to come back to the theatre and get a real-life experience.

So you see video as a complement, not a replacement?

Absolutely.

The exterior of Palais Garnier. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

I asked you this in our conversation last year, but of course so much has changed, and I want to ask again: what are you taking with you now from Toronto to Paris?

I’m not leaving just yet!

Something you’d noted before is your desire at Opéra national de Paris to highlight various historical aspects within a contemporary context.

That hasn’t changed, of course – putting historical opera within the larger context of what happens today, for 21st century artists and for a 21st century audience – that won’t change, but we’ll have to see as we emerge from this crisis, what has actually changed, and when we can go back. That (plan for return) will determine a lot. The longer this goes, the more we will have to think about smaller things we can do for limited groups of people. The goal is to go back to fully staged opera as quickly as possible, but if we can’t do that, we better get inventive. Ultimately I believe in the resilience of the art form.