Is opera in crisis? It depends on who you ask. Directors, programmers, musicians, dramaturgs, academics, and music writers alike have been grappling with what exactly opera’s place can or should be in contemporary society. Shrinking interest; dying audiences; lack of funding sources; layoffs; closures; relocations; charges of abuse; increasingly desperate marketing and juiced-up data – outside of the small silo in which opera produced, presented, shared, and discussed the signs aren’t exactly encouraging. These issues highlight a bigger problem: the perception that opera, for all of its beauty and benefits, is simply irrelevant to a great many people.

It’s an idea – or reality, depending on your viewpoint – which has come about through decades of dramatic economic, cultural, and technological shifts, not least of which has been the precipitous cuts to arts journalism. Those cuts are frequently not acknowledged by the opera cognoscenti, though such lack of awareness (or interest) is possibly symptomatic of a larger issue facing opera, one related to community. The extent to which opera companies (and their leaders) meaningfully engage with the community, and in what spirit that engagement is conducted, are hard if important questions right now; is local engagement done for marketing and optics, or does it mean something more, something outside of affirming positional privilege? Should opera reflect the place it’s presented, and if so, how? Opera is inherently linked to context; the cultures and histories of one locale can’t (and shouldn’t) be grafted onto another one. So how should opera acknowledge context? In which formats? And what role might commissions play in all of this?

One might look to New Zealand. A new report from Arts Council New Zealand Toi Aotearoa released this past Tuesday (“New Zealanders and the Arts – Ko Aotearoa me ōna Toi“, Creative New Zealand, 23 April 2024), shows public engagement, participation, and attendance in arts events all impressively up, with increased support for Ngā Toi Māori (Māori arts) as a way of connecting with culture/identity and encouraging language skills and usage. Various aspects of accessibility stand out, however; in identifying elements that would make a difference to their regular attendance, 53% of respondents cited cheaper tickets, and 30% said feeling confident they would be welcome. Might these respondents feel welcome at the opera? New Zealand Opera (NZ Opera) certainly hopes so. The company is dedicated to presenting work which reflects the people and history of Aotearoa; that focus means the country’s rich heritage and history sits at its core – and clearly manifests in the company’s bilingual website, which acknowledges a range of cultural consultants. Among the four values on its Mission & Values page is, rather notably, “Mahitahi | Collaboration“. Presenting works in a number of cities including Wellington, Christchurch, and Auckland’s Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre (named after the famed Kiwi soprano), the company partnered with the acclaimed dance ensemble Black Grace and its founder, choreographer Neil Ieremia last September. Gluck’s 1762 opera Orfeo ed Euridice was presented in reimagined form, as (m)Orpheus, with reorchestration of Gluck’s score by New Zealand composer Gareth Farr for a ten-piece ensemble that included a string quartet, marimbas, guitar, woodwind, and brass. The production was a hit with critics and audiences alike. As well as live presentation the company has a clear commitment to education – hosting a student ambassador programme; school presentations and tours; and Tū Tamariki, characterized as “a space for Māori driven works, created specifically for tamariki and rangatahi” (children and youth). Its first opera, Te Hui Paroro by music theatre artist Rutene Spooner, incorporates various theatrical elements including text, movement, and waiata. Upcoming presentations include Rossini’s Le comte Ory (opening the end of May) and a concert version of Wagner’s epic Tristan und Isolde in August with the Auckland Philharmonia led by Giordano Bellincampi.

This past week the company hosted its inaugural New Opera Forum, or wānanga, at Waikato University, located roughly 90 minutes south of Auckland. The Māori Dictionary defines a wānanga as a “seminar, conference, forum, educational seminar” as well as “tribal knowledge, lore, learning – important traditional cultural, religious, historical, genealogical and philosophical knowledge” – a definition which complements the company’s interest in music-based and text-based storytellers. Featuring composer Jonathan Dove, librettist Alasdair Middleton, and baritone and reo Māori expert Kawiti Waetford (Ngāti Hine, Ngātiwai, Ngāti Rangi, and Ngāpuhi), the wānanga is described on the NZ Opera website as “a space for story-telling creatives in Aotearoa to gather together and consider the essential steps required before starting new opera projects.” The company’s General Director, Brad Cohen, told local arts website The Big Idea in February that the idea for the forum sprang from two questions, ones relating to support for new works’ “success and longevity“, and best ways to welcome storytellers to an art form they may perceive to be one of “exclusivity and entitlement.” (“New Forum Eager To Smash Creative Stereotypes”, The Big Idea, 15 February 2024)

Cohen has a lifelong history in music – as a conductor, administrator, and founder of the immersive music platform Tido. Raised in Australia, he began playing violin at the age of four before becoming a chorister in Sydney; as a teenager Cohen won scholarships (organ and academic) to The Kings School, Canterbury (UK) and went on to St John’s College, Oxford. Studying conducting with Sergiu Celibidache in Munich and Leonard Bernstein in Strasbourg, he eventually was awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Music. In 1994 he won the Leeds Conductors Competition. (Other winners include Martyn Brabbins, Paul Watkins, and Alexander Shelley.) From 2015 to 2018, Cohen was Artistic Director of West Australian Opera. A fan of French and Italian repertoire, his track record with contemporary works is equally formidable; along with collaborations with composers Thomas Ades, Jonathan Dove, Georges Lentz and Ross Edwards, Cohen has directed ensemble works by Frank Zappa and worked closely with the celebrated Almeida Opera Festival in the 1990s. He has led the London Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic, and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Orchestras, the Philharmonia, the Stuttgarter Philharmoniker, Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte Carlo, Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra to name a few, as well as conducting operas at English National Opera, New York City Opera, and Opera Australia, and recorded on the Naxos, Chandos, and Deutsche Grammophon labels.

Named as General Director of NZ Opera in April 2023, Cohen outlined his belief in opera to national broadcaster RNZ:

For me, opera is a universal resource. It uses one very simple element, the human singing voice, and it does one very simple thing with that, and that is tell stories through the power of that singing voice. This is a resource that is the first thing we as infants hear…we hear our mothers singing to us…it’s what we grow up with, it’s the only instrument everyone is born with…and it belongs to us all.

(“The new NZ Opera: progressive rather than radical“, 14 November 2023, RNZ)

In January Cohen took part in a panel called “Conversations About Opera” and admitted he was part of what he called the “apprentice and master model” and that the current opera landscape requires “more consideration in how we collaborate.” (“New Zealand Opera boss hails changing culture”, New Zealand Herald, 21 January 2024). Collaboration has a recurrent theme throughout Cohen’s work; in a 2018 blog post closing his tenure with West Australian Opera, Cohen outlined the centrality of what might be termed the three c-s of 21st century opera: community, curiosity, and confidence. Ties to my own favourite c-word (context) are obvious; they jump out of the opera silo by simply acknowledging there’s a reality (or rather, several) outside of it.

Our recent conversation took place the week before the start of the wānanga. Cohen and I began by discussing the origins of the forum before exploring the role companies might play in cultivating new commissions, a role that goes well beyond workshops and acknowledges collaboration and related community. At a time when there are calls to “burn it all down” – “it” being the opera world – Cohen takes what has he himself has termed a progressive (as opposed to radical) approach; the opera-is-fancy clichés can go; the stories and the music remain.

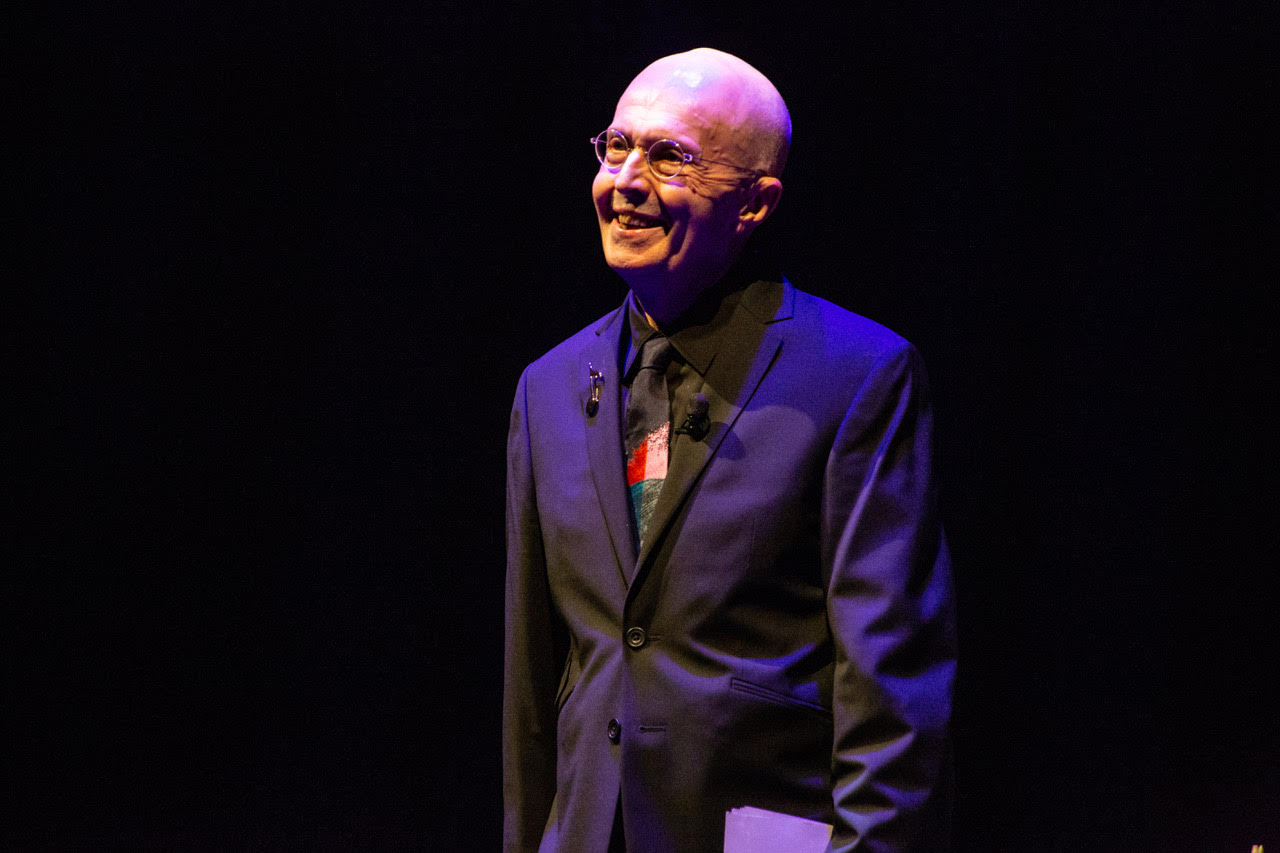

Photo: Andi Crown

How did the New Opera Forum come about?

The idea really began 35 years ago; I started out my career working at the Almeida Opera Festival in London in the 1990s – that was where I did the premiere of Ades’s Powder Her Face and a lot of other major work. We also developed many new commissions. The 1990s was probably the last decade of real confidence around new opera. There was a vision of a way forward then, that (new opera writing) was part of a tradition and that it was going to continue. My perception is that that confidence has really deteriorated and lessened over the last couple of decades. When I came into the role here as General Director, there were some commissions in progress and discussions around future commissions. I thought we needed an overhaul and that sent me to thinking: what would the preconditions be for new works? The forum is about exploring the best means of ensuring success for new work that we can – and by “success” I don’t mean first performance or run; I mean sustainability and revivability.

How does the forum aim to counteract the one-time-only issue for new opera works?

It goes back to process. My experience of working with experienced and less-experienced composers and librettists is that the historic pattern for many houses seems to be, “Here’s a chunk of money, we’ll see you in three years with a masterpiece.” At that stage, abject terror normally sets in for the music and/or text creators, because they don’t normally have experience in writing opera. They have no idea what the rules of the game are, if you like. They may not even be experienced in writing text or music for voices. There are basic things: how many words do you think a singer can sing a minute and be comprehensible? Do we really want a libretto that’s longer than Tristan when the brief has been for a 90 minute one-act? There’s a real potpourri of experience coming in, but also, from the opera companies, there’s often a real lack of shepherding. Companies will decide on the big name to give the commission to, and then they’ll step in with their direction in the six months before the premiere, in the form of workshops. In my view, and from my experience at the Almeida, that’s far, far too late. It’s the holding of creatives through the entire process that we are proposing as a better model.

The New Opera Forum (L-R) included NZ Opera Participation Manager Frances Moore, baritone Kawiti Waetford, and (bottom) composer Jonathan Dove. Photos supplied by NZ Opera.

“Revivable, Sustainable” New Operas

However, it does encounter a few obstacles because I think opera composition is one of the last citadels of the ivory tower. That is, there is an expectation amongst lots of creatives that they’re going to be given a chunk of money and that the success of the project is in simply getting the commission. Now for me, that emphasis is all wrong. The success of the project is the revivability of the piece. It’s not the getting of the commission. If everything’s inflated towards, “Okay, I’ve got this commission” and then “What the hell am I going to do?!” – that’s the wrong emphasis. How are we going to make these works revivable and sustainable? It’s about how the opera company, with all of our practical and pragmatic experience in putting work on, supports and educates where needed, but does not interfere with the creative process of these people who are writing these works.

What is the role of workshops? What should come before them?

Sometimes workshops have become little more than a PR exercise: “Hey, this piece is coming and here are some bits from it!” But by the time you get to that, it’s way, way too late. What about the robustness of the libretto? What about the dramaturgy? What about the structure? Is this going to work? Is this going to work on stage? Do we think this has a reasonable chance of working? Because a lot of the pieces that I get, you know, I mean, there’s some obvious question – like who wants to see this piece? Who wants to actually see this story? Do you have the authority and the knowledge to tell this story? Is it really your story? Is it your kind of story? Or are is this another form of appropriation? These are really big questions. One of the days of the forum we’ll have one hour focusing on story sovereignty. Some composers and librettists don’t even know what story sovereignty is, so there’s a lot of ground to cover.

There’s a strong element of didacticism within various new works, and it’s sometimes tied to grants and funding schemes. Where does that element fit in with your notions of new opera creation?

That’s a complex issue. I just want to consider your question of whether the existence of grants, to some degree, actually distorts the choices that are made downstream of that. If didacticism is becoming a part of this, is this because in some sense, the grants have a stipulation or a vision mission statement somewhere that suggests that didacticism would actually be welcome? I think I, like you, don’t really feel that didacticism is germane to opera, necessarily. I don’t think historically it’s played that well or successfully and I think if you want to teach and to create teachable moments there are probably far better media to do that.

Gatekeeping In Opera

In terms of our commissioning there’s a lot of dishonesty. I think a lot of people say, “Oh we’re not gatekeepers!” – but actually, I am. I’m pretty much the only gatekeeper in this little corner of the world. I am leading the only opera company here with national reach. I am pretty much the path through which all decisions about commissioning or not commissioning go – and not just commissioning work, but who directs, who produces, who sings, who is cast, all of that. I am ultimately responsible for those decisions. So it doesn’t behove me to say “Oh, you know, we don’t like to think like a gatekeeper.” You know what? We as companies are the gatekeepers; there’s no getting away from it. Someone has to say yes or no. And the biggest part of my job normally is saying no. That’s just the way it is, and I accept the responsibility, but I’m not going to be dishonest about that. Someone has to press go or no-go on all of these projects.

We are not a grant giving body; we source commissioning funds from trusts, foundations and other institutions, but we are still the conduit through which those funds come to creators. The question is, how can NZ Opera support artists better? And by “support creators better” I do not mean, “how can we give you more commissioning money?” – that’s not the point of the question. The question is, what do you expect from a national opera company in terms of their responsibility towards you? Because opera commissioning is an unavoidably expensive process. There’s some sense of adult responsibility here that we’re really keen to discuss on that final forum day; we’re adults, let’s all act like adults and have a serious discussion about what our responsibility is as the national opera company towards creatives, but also what responsibility do creatives have towards the National Opera Company, towards our narrative, towards our journey. It’s a sense of mutual obligation, ideally, and that contract, if you like, is very rarely explicitly stated.

That mutual obligation is made extremely clear on your website – how does that work in terms of the company’s diversity?

I don’t frame it around Māori and non -Māori; we frame it as, we are here to serve our community or, alternatively, communities in a multiple sense. There’s a lot of complexity here around Māori hiring, our bicultural journey going forward, and there’s a lot of complexity politically, with the new, more right-wing government. I won’t use the phrase “cultural war” but there’s an aspect of a culture war developing here right now and as the national opera company, we are right in the middle of that. We feel that we have been given a responsibility, but it’s not like we’re inside and the others are outside. In fact, in many ways, we are outside. We’re outside the main thrust of culture as opera people; we’re outside the main way that people spend their time and what they want to go and see. It’s a very parochial if very common thing to think, “We are at the seat of power and we will open our doors to these lovely creatives from various communities and let them have a chance to play” – for me, the model is exactly the reverse of that. The opera industry as a whole is holding on by our fingertips – we are on the verge of irrelevance – and everything else is either deception or self-deception. I don’t have any time for it.

Cohen (centre) in rehearsals for NZ Opera’s 2024 presentation of Mansfield Park, speaking with Principal repetiteur David Kelly (right). Photo: Jinki Cambronero

Storytelling As Foundation

So if we’re going to serve our communities, what is necessary? What I do is simplify everything to the pithiest possible message, and the only way that I really approach new work, is to see who is the best storyteller and who feels that they both have to tell them and that they have the competence to be able to articulate them. That is really where it stops and starts for me.

If you’re a composer – whether a white male composer or a female of colour – and you’re not interested in storytelling, you’re not a good match for our organisation here, because storytelling – we’ve made it very explicit – is what we believe in and we are about. We want to tell stories not only about our communities, but ones with historical awareness of this nation’s narrative. What part do we play in the narrative going forward? That’s a really big responsibility, but we try and wear it as lightly as possible, not by saying that we are The Chosen Ones and we’re going to occasionally allow a chink of light in so a diverse someone can slip through and become anointed by us – no! It’s about who has great stories to tell and if those who do have any interest in working within the operatic art form. If not, is it because they’re genuinely not interested? Or because there might be some misunderstanding about what opera is – i.e. “It’s not for me because it’s elitist, it’s exclusive” or “They wouldn’t want me anyway”? What we’re saying, really strongly, is that we want great stories – stories that are about us, now, here in this place. We have advocacy and persuasion to do; the way that opera has sold itself for the last hundred years is not the core of what it actually is.

You’ve said in many interviews that the whole “elite” cliché around opera has to go.

Yes, you’ll hear me say it again and again: opera is not about the champagne; it’s not about the black tie. Those things can be part of it, sure, but that’s not what opera is. Opera is storytelling through the human singing voice. Period. I just say that ad nauseam, because that is the most condensed form of definition of what opera is. What’s the quality of the storytelling? Does it reach the heart? Does it speak to audiences? Is it something that people want to come and see?

Photo: Andi Crown

Who decides what’s great or not then? Who decides on that definition as applied to the art form?

It’s a pretty intractable problem. You can abdicate from your responsibilities as gatekeeper and you can say, right, we’re throwing it entirely open, no one’s going to make a decision about this! Then what’s left to you? You could mount competitions too, but at the end of the day someone is always saying “go” or “no-go. ” Always. It doesn’t matter who. It could be the board; it could be the funding body; it could be the GD; there is no world in which work is entirely self -generated and rises to the surface and gains performances without someone at some stage going, “Yes, we’re going to go with this” or “No, this is not for us.” There’s no way around that. The longer-term solution is that my successor is a Māori person – that’s the obvious result of everything I’m doing, and it is my own thinking about succession. I’m not on my way out yet, but it behoves every leader to start thinking about succession immediately. The logical next step for a country who is engaging with these narratives and taking its responsibility to the whole community seriously is that it shouldn’t probably be a white, Oxford-educated male who replaces me. That’s what I am, right? It doesn’t matter how liberal I am.

“Consistent and determined”

A scene from the 2023 NZ Opera production of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte, directed by Lindy Hume. Photo: Jinki Cambronero

Is it fair, then, to say the Forum is aimed at both creators and a larger classical ecosystem?

It’s absolutely aimed at the ecosystem – we hope that it is going to be a nourishing activity that will send tributaries out into the ecosystem – but that’s not our intent; I hope that it’s going to be a consequence. And for clarity, we are being very explicit that we are not aiming for outcomes from this one; this is a space for reflection, for safe discussion, and for erecting an intellectual superstructure around the space in which we can create new work. We’re not going to have workshops in this one; that’s not what this is about. This is really pushing the walls out to create a safe space and a way to say to people, “Hey, you might have an interesting story we want to hear.” And one of my hopes is that some of the more marginalized voices who may be attending the wānanga will go back to their networks and say, “You know, they might not be full of shit; they might actually have a little bit of understanding.” That’s the best we can hope for. We are very consistent and determined at NZ Opera about the journey we’re on, and our messaging and our communication reflects that.

“Oh, they actually mean it; this isn’t just optics.”

Yes we do mean it! I’m very passionate about it because… my big stick is, I feel like I’m a slight subversive within the establishment, and I’ve watched opera alienate its audiences for my entire life, and I love it too much to let that continue. So I’m doing what I can and encouraging subversion, not merely for subversion’s sake, but in order to refresh this art form and make it purposable going forwards – that’s my mission in life. I think it’s what the art form needs so desperately.

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “

So how much do you see crowdfunding being a model for creative endeavours in 2021 and beyond then?

So how much do you see crowdfunding being a model for creative endeavours in 2021 and beyond then?