For many in the classical world, summer means one thing: festivals. In continental Europe, the UK, and North America, outdoor festivals celebrating both opera and orchestral works, not to mention chamber music, are unfolding, with a certain joy more palpable this year than others. After so many experimental iterations (especially in Salzburg, where the festival powered through the worst of the pandemic in 2020), there is a firm, fond embrace of the familiar, and one hopes, a bit of a face toward the future in terms of programming, casting, productions, and (one hopes) safety protocols.

Fans of composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) will have already long planned a pilgrimage to Bayreuth, founded by Wagner himself in 1876 and built expressly to manifest his groundbreaking concept of Gesamtkunstwerk. Getting there takes a bit of planning; the town can be reached by train (from Munich it’s roughly a two-hour journey through Nuremberg) and tickets to performances require completing an early application, though online purchases were made available at the end of May. Local hotels are booked months in advance – usually; a quick check shows they aren’t all quite full this year, owing, perhaps more than anything to lingering effects of covid/omicron. Just how the classical world continues to navigate this challenge depends on who you ask; many are soldiering on, but there are also many cancellations and fill-ins, onstage and in the pit. Audiences are somewhat skittish about returning to indoor spaces – and again, the level of skittishness depends on who you ask, and where they’re travelling. The Festspielhaus, (in)famous for its uncomfortable seats and lack of air circulation, is mostly wood, as per Wagner’s wishes – as such, the nature of the house’s architecture simply doesn’t allow for modern interventions à la AC, a challenge given Germany’s increasingly steamy summers. You will experience Wagner’s works the way he intended; if you have to endure physical discomfort to do so, well, so be it. With the opening of the festival on 27 June with Tristan and Isolde (featuring tenor Stephen Gould opposite soprano Catherine Foster), there occurs the kind of sonic immersion Wagner aimed for; Wagner’s magnificent score has this odd (oddly discomfiting, for me) way of utterly erasing… time, circumstance, the edgeless, blunt forms of sameness that have been a hallmark of pandemic life thus far, the immediacy of mediocrity (and arguably the immediate realities of a hot, airless auditorium). As I’ve written in the past, my ears have lately developed teeth, a reaction to the prevailing attitude of safe-and-boring programming that colours far too much of post-pandemic classical life; Wagner offers up a chewy, delicious eight-course feast, then demanding even further capacity and appetite.

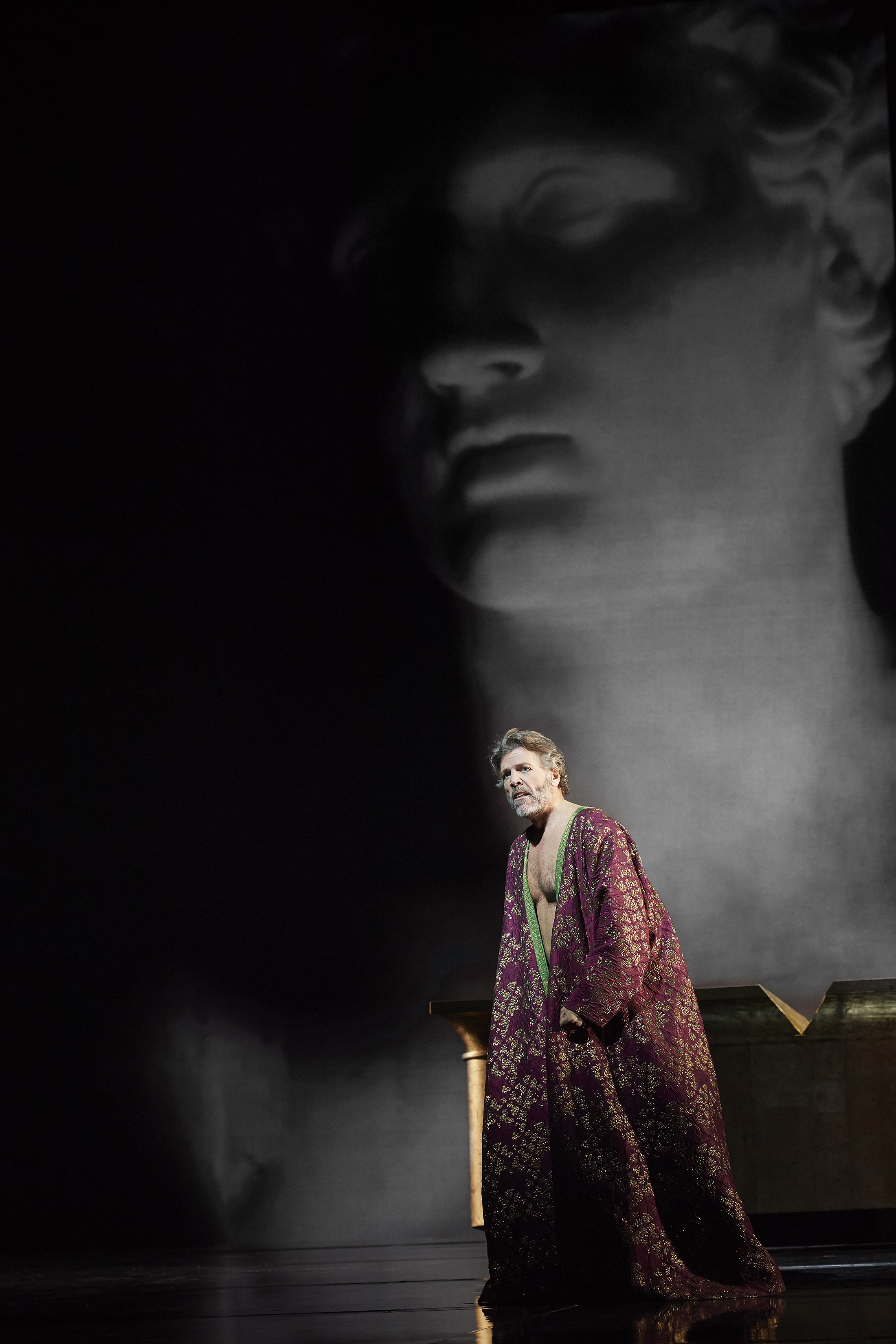

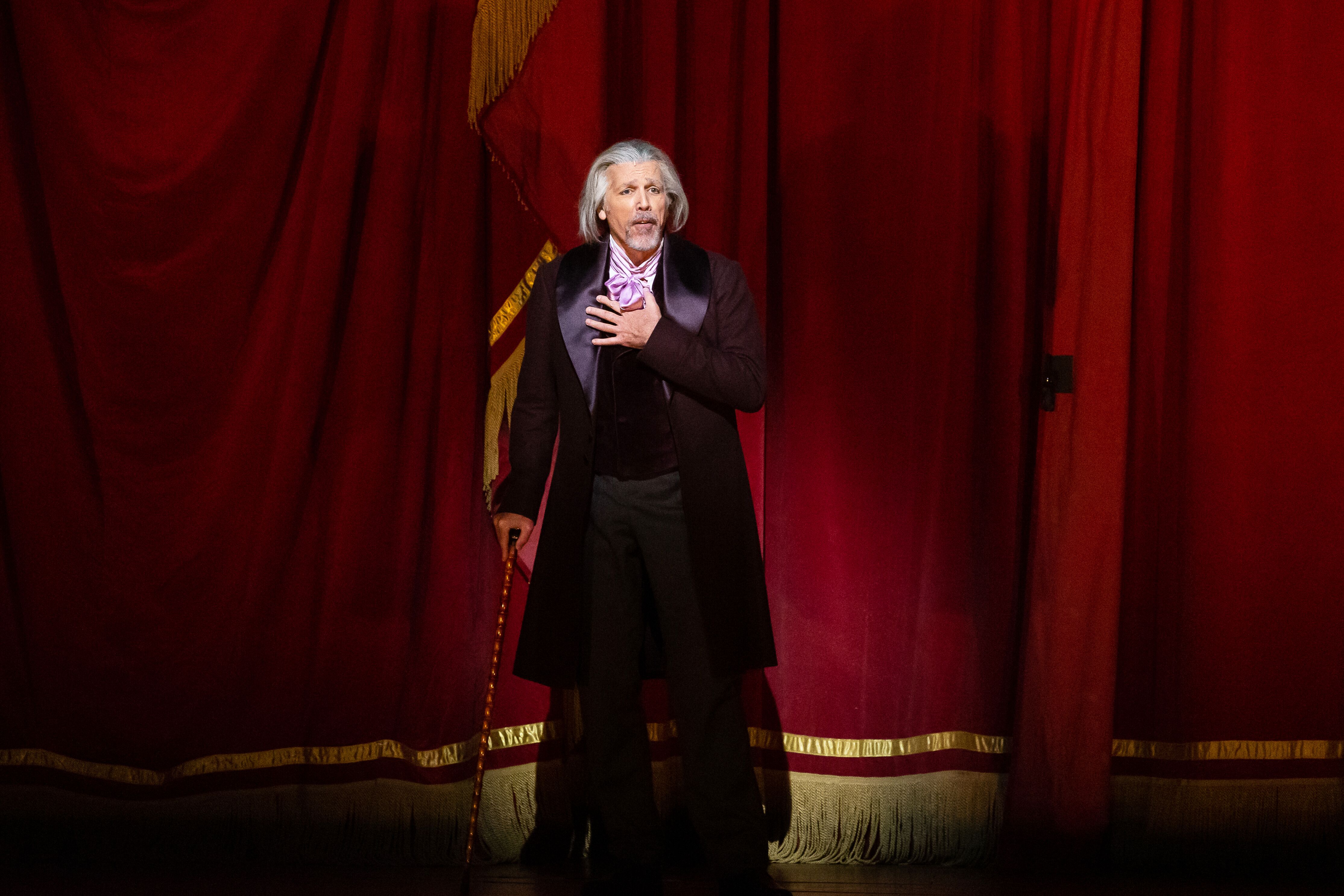

Something strangely similar in terms of sonic experience occurred in Weimar in August 2018, when I attended the world premiere of the first act of Franz Liszt’s Sardanapalo, a presentation which had been 170 years in the making. Liszt (1811-1886), a composer known far more for his piano work (compositions as much as his famous performances), never completed a full opera. Sardanapalo was based on the tragedy by Lord Byron, (published in 1821) and began life in sketch-form in 1849, with Liszt using abbreviations and creating alternative versions, eventually coming to a 115-page manuscript. The project fell by the wayside when the composer was unable to find a proper libretto for the second and third acts. Catalogued in 1910, the work was considered too incomplete for performance – until British musicologist David Trippett came across it at the at the Goethe and Schiller Archive in Weimar in the early 2000s, and subsequently spent years painstakingly piecing it together. Presented by Deutsches Nationaltheater and Staatskapelle Weimar with soloists soprano Joyce El-Khoury, tenor Airam Hernández, and bass baritone Oleksandr Pushniak all under the baton of Principal Conductor Kirill Karabits, the work has sonic connections with Wagner’s 1845 operaera Tannhaüser (something Karabits had noted prior to the premiere) and an equally clear nod in orchestration to Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) though its insistent melodicism and pungent scoring also recall Verdi’s Nabucco (1841) and Simon Boccanegra (1857). Sardanapalo demands much of its listener (one indeed needs toothsome ears here), but it offers compelling characterization through its orchestration, scoring, and mix of creative influences – indeed, hearing it inspires many thoughts around possible live presentations that go beyond in-concert formats. A recording of the work was released via Audite in February 2019 (done in Weimar), and a performing edition of the score released by Schott in summer 2019.

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical contexts) palpable and infectious. This exchange was a fortuitous and good bit of timing personally – I have long considered bringing on new contributors to my website. The advantages of new voices are myriad, their wealth of knowledge, experience, and passion immense – you don’t always want one voice or viewpoint on any given topic, but a multiplicity of voices and related experiences in order to make the meal that much richer. This seems especially important in classical, which can very often feel like a small, airless bubble. Vukosavljevic has a natural curiosity (he mentioned in recent exchange that his hobbies include “stargazing, reading, playing chess, socializing”) and his knowledge of (and obvious enthusiasm for) the classical world makes one hope for further contributions, and further journeys up in music history, composition, and performance. Thank you Dejan, and thank you Professor Trippett – if I can’t go up the hill to Bayreuth this year, I am happy to go up the hill of music history and learn something new along the way; I hope readers will join us.

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical contexts) palpable and infectious. This exchange was a fortuitous and good bit of timing personally – I have long considered bringing on new contributors to my website. The advantages of new voices are myriad, their wealth of knowledge, experience, and passion immense – you don’t always want one voice or viewpoint on any given topic, but a multiplicity of voices and related experiences in order to make the meal that much richer. This seems especially important in classical, which can very often feel like a small, airless bubble. Vukosavljevic has a natural curiosity (he mentioned in recent exchange that his hobbies include “stargazing, reading, playing chess, socializing”) and his knowledge of (and obvious enthusiasm for) the classical world makes one hope for further contributions, and further journeys up in music history, composition, and performance. Thank you Dejan, and thank you Professor Trippett – if I can’t go up the hill to Bayreuth this year, I am happy to go up the hill of music history and learn something new along the way; I hope readers will join us.

DV: How did COVID-19 pandemic influence your work as a musicologist and a cultural historian at the University of Cambridge? Where did you feel the biggest pressure?

DT: The world seemed to change in the blink of an eye, didn’t it? We instantly become online avatars, and adapted courses to keep all paths of study on track. But no online medium can replace the vibrant atmosphere of the seminar room. Looking back, lockdown feels like stolen time. Oddly, though, there were also benefits – like a lot of reading and exploring new repertoire, along with innovations in mediatized performance and testing the limits of multitrack performance. Digital resources are excellent for 19th-century studies, where many manuscripts are available online. This is the case for the Richard Wagner Museum and the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, both of which I use often in my work. So, if anything, the pandemic increased my reliance on these resources. Where was the biggest pressure? I would say the lack of contact, which was strangely alienating even as so much music went online. In concert, music touches you – literally so. Touch is the sense that unifies all other sense modalities. A singer’s voice or the vibrating reed sets in motion a pressure wave that physically touches your middle ear. Not experiencing that proximity to real acoustic sound, collectively as part of an audience – with its capacity for beauty, curiosity, and catharsis – was difficult.

DV: Your work encompasses many areas of classical music. What was your motive to begin to study the life and works of Richard Wagner?

DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (Wolfgang Sawallisch, Daniel Barenboim, Bernard Haitink), the third time with libretto in hand, and I began playing all the vocal scores. As a student, I remember travelling to Helsinki just to hear Leif Segerstam conduct the Ring. Wagner’s intellectual reach is unparalleled in 19th century music and philosophy, and, aside from the sheer richness and power of the music, the range and quantity of his ideas and commentaries, and the copious evidence of the manuscript sources proved irresistible. There is still so much work to do.

DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (Wolfgang Sawallisch, Daniel Barenboim, Bernard Haitink), the third time with libretto in hand, and I began playing all the vocal scores. As a student, I remember travelling to Helsinki just to hear Leif Segerstam conduct the Ring. Wagner’s intellectual reach is unparalleled in 19th century music and philosophy, and, aside from the sheer richness and power of the music, the range and quantity of his ideas and commentaries, and the copious evidence of the manuscript sources proved irresistible. There is still so much work to do.

DV: Would you label yourself as a Wagnerian? What do you see in Wagner’s music that makes him so special?

DT: The history of ‘Wagnerians’ makes any such label tricky. That’s one of the fascinating aspects of the Wagner historiography. On the one hand, few would want to align today with the likes of Houston Stewart Chamberlain or Winifred Wagner, both of whose curation of Wagner’s legacy was intertwined with bad politics; on the other hand, his works are continually reimagined for our time by directors, as when Siegfried’s body was draped in the Ukrainian flag in Madrid last month, or when (director) Peter Konwitschny situated Lohengrin in a German school. What remains constant is the powerful nature of the music, its continual colouristic and harmonic flux, and the ongoing psychological resonance of the drama.

Early on, leitmotifs were wryly dismissed as dotty ‘calling cards’ or ‘an address book’, but beyond simple signs, they convey the way that memories change, and the different experiences of time passing. When Siegfried shatters Wotan’s spear, its significance reverberates backwards and forward throughout the entire cycle. The Greek model of an orchestral commentary, too, offers a dynamic structure in continually re-evaluating the significance of events. That said, Wagner’s sophisticated orchestration and motivic techniques change significantly across his oeuvre – so there isn’t simply the leitmotif technique. Listening before and after the Act III Prelude to Siegfried (the densest compression of motifs to date) makes this particularly stark.

Beyond this, Wagner absorbed the values and learning of his age, so his works faithfully and fatefully refract these interests, from anti-vivisectionism to purification by holy fire. The director Michael Hampe once put it to me that Wagner’s works are ‘miracles of humanity’, and that opera directors might begin by asking ‘how do I present this so that others will understand this immense value?’ I think it’s a wonderful question.

DV: Your first monograph Wagner’s Melodies, published by Cambridge University Press in 2013, examines the cultural and scientific history of melodic theory in relation to Wagner’s writings and music. How did it start?

DT: I became fascinated with the paradox that Wagner placed ‘melody’ at the centre of his aesthetic theories (‘music’s only form’), yet he was consistently ridiculed by critics for being unable to compose a melody. The book uses this basic incongruity to re-examine Wagner’s central aesthetic claims, and places his ideas about melody into the context of the scientific discourse of the age: from the emergence of the natural sciences and historical linguistics to sources about music’s stimulation of the body and inventions for ‘automatic’ composition. Researching and writing it at Harvard and Cambridge was a fascinating experience. It led me to explore all manner of sources, from Wagner’s insertion aria for Bellini’s Norma, to a device called the psychograph for transcribing your unconscious musical thoughts… it gave me a chance to ask why it had become so difficult for German writers even to define melody (and—for most—quite impossible to teach it), and why melody simultaneously occupied the centre-ground of expression in opera, yet sat at the apex of artistic self-consciousness for German composers. Thinking about melodic intensity without actual, Italianate melody changed the way I listened to certain music – yes, I think it did.

DV: Wagner composed thirteen operas in total, but was also his own librettist; how would you describe his approach to literary writing?

DT: Wagner’s alliteration, coordinated speech roots, and creatively antique forms of language often raise a smile. Unlike, say, his orchestration, it was an area of his work that was openly questioned by contemporaries. For me, the opera poems after 1850 reflect his theories about language and of how language communicates, and these change, of course – which is why you find a diatribe against rhyming, metrical verse in his essay “Opera and Drama” (iambic pentameter as ‘five-footed little monsters’), yet a return to precisely such verse in Meistersinger fifteen years later. Ever pragmatic, his underlying goal in what he called ‘verse melody’ was to uncover a musically infected form of communication that couldn’t fail to be understood, even (especially) by those with no training.

There are various librettos that he completed but never set to music, including a quasi-Buddhist drama (The Victors), and a vaudeville about a cross-dressing bear (The Happy Bear Family). He held all of these poems dear, and suggested to other composers, including Liszt, that they set them instead. So fiercely did he feel that the Ring poem was a work of world literature, that he published it in 1853, as a book, though he came to regret that decision! Even accepting the importance of his theory of speech roots that rhyme and concatenate sounds, we now tend to use Wagner’s language more as an artistic means, for music, rather than celebrate it as literature.

DV: You were the Main Editor of the book published by the Cambridge University Press in 2019, Nineteenth-Century Opera and the Scientific Imagination; the book features, among other things, the so-called “Wagnerian manipulation” – what is its connection to Bayreuth?

DT: Much has been written about Bayreuth as a proto-cinema, but I think the desire to control an audience’s sensorium was only part of the story. Since his time in Dresden during the early 1840s, Wagner had been advocating practical innovations to his theatre (like enabling sight lines, updating the instruments, pensioning off the weakest performers), and his friendship with the brilliant architect Gottfried Semper — who designed the barricades Wagner defended during the uprising in May 1849 — shaped his ambitions for what a theatre could be. Add to this the explosion of contemporary research into sense physiology under figures like Johannes Müller and Helmholtz, and Wagner’s own belief that audiences had to physically experience music, first-hand, in order to ‘get it’, and it is not hard to see why the Festspielhaus project came about. Nor why it has become a focal point for the history of a specifically Wagnerian culture in all its stripes. Wagner sought to do away with mediating explanations, where ideally the entire role of music criticism would become redundant – in many ways Bayreuth was conceived as a monument to that ideal.

DV: Franz Liszt was the composer who helped raise the profile of the exiled Wagner by conducting the overtures of his operas in concert while he was in Weimar. How would you describe the relationship between the two composers?

DT: In a word: asymmetrical. They first met in 1841. Initially, Wagner pursued Liszt more for career advancement than artistic kinship, sending him the scores for Rienzi and Tannhäuser (‘I proceed quite openly to rouse you up in my favour’). By 1848, he began requesting financial help from Liszt, initially selling the copyright to his extant operas and accepting commissions, but thereafter simply requesting a series of bailouts, often in uncomfortably obsequious, manipulative prose. 1849 marked a sea change: Liszt was enormously impressed by Wagner’s latest works, which he felt were at the vanguard of progress. He conducted Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, making sets of piano transcriptions of both (a supreme endorsement), he sought to conduct Siegfrieds Tod (had Wagner finished it), and even asked to premiere Tristan und Isolde in Weimar. During the 1850s, Liszt had the fame, influence, resources, and financing to rescue Wagner from critical and political ignominy as a composer-criminal, ingloriously expelled from Germany in 1849. Perhaps most significantly, he was a key figure in securing Wagner’s eventual amnesty and in promoting the first fledgling Bayreuth festivals.

But by the end, he referred to himself as ‘Bayreuth’s poodle’ after being wheeled out as a celebrity to endorse the second festival, after Wagner’s death (in February 1883). Wagner had questioned the comprehensibility of symphonic poetry in 1857, and would (privately) dismiss Liszt’s late works as ‘budding insanity’. There were two rifts in 1859 and 1864, the first over a misreading of tone in Liszt’s remarks about Tristan, the second more serious – about the Cosima affair (Wagner to Cosima: ‘Your father is repugnant to me’). So despite an early period of genuine, intense artistic friendship on both sides, the relationship was always lopsided. There is much more to say, of course, and I’ve written about this in the Cambridge Wagner Encyclopedia (2013; Editor Nicholas Vazsonyi).

DV: Liszt was a prolific composer, but spent nearly seven years on Sardanapalo, an Italian opera based on Lord Byron’s play. How did Sardanapalo come about, and why do you think it became such a challenge for him?

DT: By his mid 20s, Liszt’s ambitions for the ‘social mission’ of art exceeded mere pianism. By his early 30s, he saw how Rossini and Meyerbeer towered above other composers in Paris. Their medium? Opera. In his eyes, the spectacle, size, expense and public appeal of Franco-Italian opera ensured that this was the privileged route to such power, to entering ‘the musical guild’, as he later put it. Schumann had written publicly of a ‘disconnect’ between Liszt’s two identities, as a great pianist but less developed composer, and it must have hurt. The opera Sardanapalo was born of ambition (‘to cross my dramatic Rubicon’) – and it sounds like that. Liszt was intimately familiar with French and Italian opera scores of the age (that is, transcriptions and paraphrases), so composition of his mature opera was remarkably fluent; the libretto was his Achilles heel. He had searched widely for the right topic, eventually settling on Byron’s tragedy Sardanapalus in 1845. Sadly, he wasted several years waiting for the playwright Félician Mallefille (1813-1868) to fulfil the libretto commission. He finally accepted a text procured by his close friend the Italian Princess Belgiojoso, a well-connected writer and salonnière exiled in Paris. We don’t know who this poet was – he was reportedly imprisoned for agitating towards Italian independence, and in need of funds! Liszt worried that he was no Byron or Metastasio, and implored Belgiojoso to work on the text herself so that it would emerge under her authority (‘Permit me simply to place my entire musical destiny in your beautiful hands’).

When the versified text for Act 1 finally came through, Liszt set it to music in a detailed, continuous short score (a particell). It took many letters, follow-ups and prompts, including the threat of commissioning a new poet, to extract the versified libretto for Acts 2-3, but Liszt never set them. He questioned aspects of the libretto to Belgiojoso, and evidently wanted changes made before setting anything further. As far as we know, no revised libretto was ever sent, and by this time (c. 1852), Liszt was so deeply involved in other compositional projects, not least the symphonic poems, that the zeal and original reason for completing an Italian opera a decade ago had faded.

DV: The score for Sardanapalo was thought to be almost impossible to read, and its music irretrievable. What was your approach in its reevaluation and eventual presentation in 2018?

DT: I was puzzled by the idea that a musician as intelligent as Liszt would have notated musical materials that were full of errors or made little sense, as some had suggested. The problem was more likely to be that we were reading his manuscript incorrectly. When I began studying the manuscript in detail, parts of it were legible, but at first glance it looked incomplete; Liszt used many abbreviations and forms of shorthand – like mini-codes to himself – to get everything on paper at pace. I made about 15 transcriptions of the full manuscript. With each new transcription, the contents became clearer. It was a bit like a very pixelated image gradually coming into focus, in ever-higher resolution with each transcription. Liszt was writing for his eyes only, so a lot of accidentals, signatures, rests etc. were missing. Fortunately, the vocal parts were complete and continuous – fully notated with text underlay. In three places, the accompaniment appeared to drop out, creating odd gaps with continuous vocal parts above. The solution was that Liszt in fact sets up clear, formulaic accompanimental patterns that would continue; in an age before cut & paste, he simply didn’t feel the need to write them out in full.

DV: How did the research process for Sardanapalo unfold for you?

DT: It was a genuine leap of faith. I had no idea what the manuscript would contain when I began, but as the project progressed, I felt a growing responsibility to bring the remarkable material he wrote to light in a way that was both scholarly and historically sensitive. There is a very detailed commentary in the critical edition (Neue Liszt Ausgabe), and a major question that remained was whether or not to orchestrate the work. As written, the short score is often unplayable on the piano, and Liszt left a few cues for instrumentation, even specifying orchestral textures in detail here and there. (Following normal practice, his assistant Joachim Raff was due to produce a provisional orchestration in 1852, which Liszt would then have revised.) It was clear, then, he was thinking in orchestral colours. For that reason, I felt the music should be presented in fully orchestrated form as well as in a critical edition.

Beyond this, it was enormously valuable working with several young singers from the Jette Parker Programme at the Royal Opera House, and later, with (conductor) Kirill Karabits and the three singers (Joyce El-Khoury, Airam Hernández, Oleksandr Pushniak) who performed the full world premiere. Although Liszt notated the vocal parts in full – for instance, with all ornaments, phrase markings – many details for performance still had to be discovered by trying out the music, and seeing how it fits in the voice: tempo, transitions, articulation, shape. All of this could only be explored by making the leap into sound.

Oleksandr Pushniak, Airam Hernández, Joyce El-Khoury and David Trippett at Staatskapelle Weimar on August 19. Photo: Candy Welz

DV: What were your impressions from hearing the world premiere in Weimar?

DT: It was a revelation. The performers were so committed and inspired in bringing this to an audience, and the orchestra – Liszt’s own orchestra, in his adopted city – was magnificent under Kirill. It had the feel not only of creating history, but of history folding back on itself, as though in an alternative reality the opera had finally materialized in all its splendour. That first performance was released as a CD, and it was such an achievement for all concerned, topping the UK Classical charts, ICMA finalist, making the Guardian’s Top 10 discs of 2019. I have such admiration for all the performers.

DV: The opera had concert performances lined up this year in Budapest, Edinburgh and London, but things got frozen due to COVID-19 pandemic. What are your plans for the future?

The pandemic froze many exciting artistic projects, and Sardanapalo was no exception. There are some discussions ongoing for future performances in Hungary and America, but it is sad to think that the music waited 170 years to be heard, had a moment of glory and began spreading with momentum, only for it to be silenced again by the cruel effects of the pandemic. I would hope that Liszt’s ingenuity in creating a modern, through-composed bel canto opera will continue to be enjoyed by audiences. And, it’s crucial to note here that following detailed work on the critical edition, the final, fully corrected score has yet to actually be performed – there is a striking difference at the end of Mirra’s cabaletta, for example.

DV: Do you believe that Sardanapalo could find its way into the repertoire of the opera houses in the near future in some staged production?

DT: It would be a creative opportunity for the right director. Could it be staged? Yes. Without doubt. The action is largely psychological – interior – but that is no different to Tristan (Wagner) or Bluebeard (Bartók). The challenge would be how to couple it with another one-act opera that complements Byron’s drama. Liszt frames the act with a concubine chorus and the royal army marching off to war; in between we have the adulterous couple learning about each other’s passions, insecurities and power, and on stage is the silent wife.

In today’s world of conflict, King Sardanapalo’s firmly anti-war stance resonates (‘Every glory is a lie, / if it must be bought with the weeping / of afflicted humankind.’), and the outer action pivots on Mirra’s plea that the he overcome this aversion to violent conflict, that he stand up and defend the realm. He listens and is finally persuaded by her lyricism – so off they go to war. It certainly offers plenty of creative material, from the opulence of ancient Assyria to the irony of a brutal Byronic hero who loves peace – 2024 is the 200th anniversary of Byron’s death, so who knows?