What’s the c-word? Regular readers and former students might know the answer. Likewise Cambridge University Press, whose In Context book series is dedicated to multifaceted explorations of law, literature, music, and ideas. The collection offers much more than life-and-times surveys by highlighting detailed and often surprising aspects of those lives and those times via deep dives on tangibles (money, partners, projects), intangibles (ideas, philosophies, lifestyles), socio-cultural trends, and, in the case of music, elements of composition, recording, and reception, as well as historic and contemporary interpretation and practice. Through an interconnected series of brief if in-depth essays, material is presented with thematic and chronological considerations, with each essay curated in order to illuminate its surrounding colleagues. The series is an indispensable resource for both fans and scholars, with its composers series exploring an array of famous names, including Puccini, Brahms, Mozart, Mahler, Stravinsky, Strauss and The Beatles.

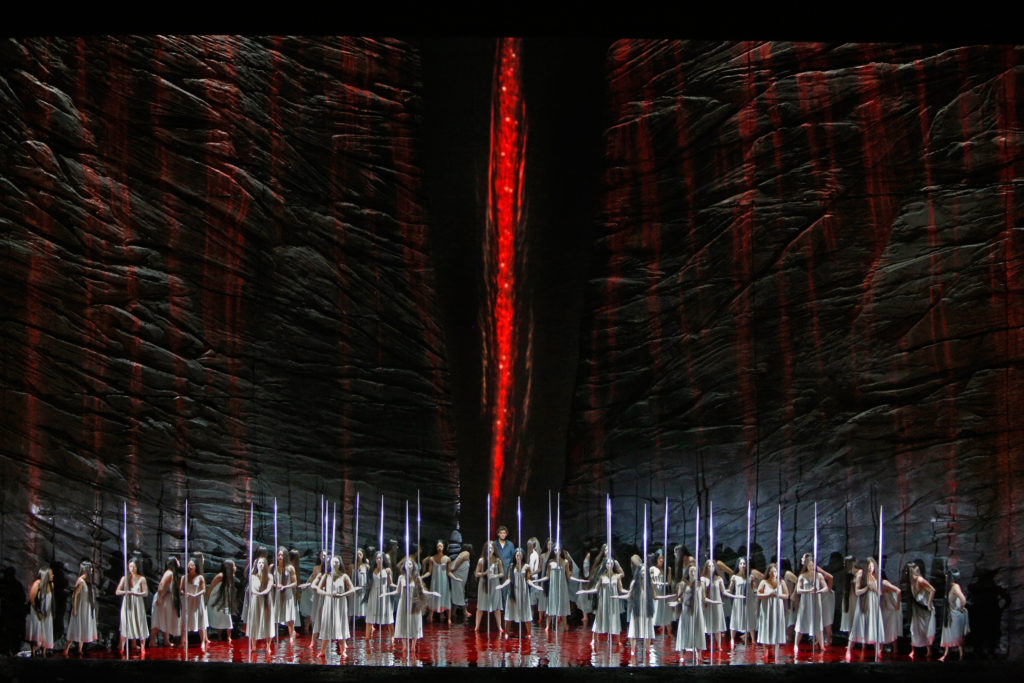

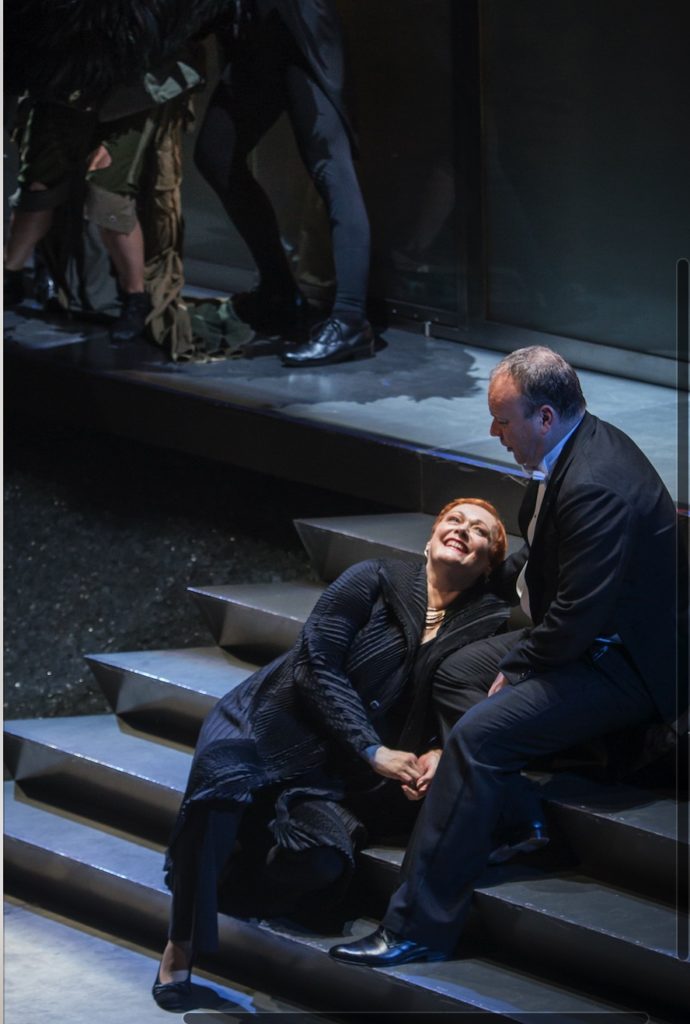

Wagner in Context (Cambridge University Press, 2024), released this past March, contains 42 essays by music scholars, writers, and other classical figures (including conductor Leon Botstein), all probing the life and legacy of composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Divided into six sections including geography, politics, people, performance, and reception, the book offers meaty dives on well-known topics (i.e. The Ring and its stagings through time), practicalities (money), realities (criticism), as well as pointed socio-cultural examinations (performing his work in Israel; Buddhism, video game music). The book’s release is particularly timely what with houses in Zürich and Berlin having presented complete Ring cycles recently, and those in Milan, Munich, and Paris (the latter featuring Ludovic Tézier as Wotan) starting in the 2024-2025 season. Amidst the contemporary online discourse – alarm that opera is in a state of crisis and/or “burn it all down” and/or “the old days were better” – actual interest in Wagner and his work would seem to be growing in leaps and bounds, even if audiences at historic houses like Bayreuth have grown shaky.

Musicologist David Trippett, Editor of Wagner in Context, has assembled a rich collection of essays, many of which speak to these communities and ongoing conundrums. Professor of Music at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Christ’s College, Trippett was also the guiding force behind the rediscovery, reconstruction, live presentation and recording of Franz Liszt’s lost opera Sardanapalo in Weimar in 2018. The author of Wagner’s Melodies (Cambridge University Press, 2013), he has also edited collected volumes on music and science as well as music in digital culture. His own essay for Wagner in Context (“Sentient Bodies”) is a thoughtful contextualization of the composer’s tonal language via its sensory effects, using historical and philosophical frameworks; Nietzsche’s infamous 1888 claim that “Wagner increases exhaustion” is its starting point. In the introduction Trippett offers a thorough examination of the meaning and role of context as related to the composer and his legacy, fusing old and new with immense confidence. He raises the reality of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (which occurred during the book’s editing process) and in noting the presence of the Wagner Group and the Mozart group writes that “these tatty battlefield personae beg the question of how reception contexts engineer and amplify such different moral valences, and what and what role is played by the signs and nodal gateways of modern media in their dissemination.” The connection to the immediate subject matter, and his overarching shadow on contemporary opera life, couldn’t be made clearer.

Still, I was curious as to the process of editing a book on one of classical music’s most (in)famous figures. In conversation, Trippett is involved, detailed, fascinating to speak with, his engagement warm and friendly. There’s always something new to learn about Wagner, and, as this conversation proves, lots more to talk about. The c-word is indeed a grand and wondrous thing.

The Selection Process

You have an array of distinguished contributors in this book, and I’m wondering how you chose them, and, relatedly, the way that the chapters and respective contributions are divided; did you approach people like Mark Berry and say, “I need you to write about revolutionary politics,” or Leon Botstein with “We need an article about America” ?

The first thing to say is that I think the quality of contributors is a vote of confidence in the field of Wagner studies. People want to write about Wagner and there is so much that changes with time – so when we listen to works, reread his writings, and see how the world has changed, the meaning of those works and those writings changes also. There is a perennial reinvention that takes place, and I think in looking at contributors I really was inspired by people whose work I admire. It really was a case of asking myself two questions. On the one hand, there was a sense of thinking, what does a book like this need? Wagner had so many interests and it would be impossible to chase them all down and try and do a serious scholarly dive into vegetarianism, or into his trouble with debt, or his attitude towards women; there isn’t space. These are short chapters; they have to be bite-sized, like a kind of elite tasting menu.

The other equally important question was, whose opinion do I want? Who would be really good to write about this? So to pick at random, the head of The National Archive for Wagner Studies in Bayreuth is a wonderful Wagner scholar, Sven Friedrich. I happen to know that before he moved to directing the Richard Wagner Museum in Bayreuth, the Jean Paul Museum, the Franz Liszt Museum, and the National Archive and Research Centre of the Richard-Wagner-Stiftung, Sven had a career in banking – his training is in finance – so he knows a lot about the area of merchant banking and money. I suggested to him to look at the copyright and the royalty situation for Wagner (“Wagner’s Finances”), and to translate his findings into current figures, in order to really try to understand whether the myths and the easily-parroted opinions about Wagner are warranted; I was very lucky that he agreed.

And you mentioned Leon Botstein, who is such a learned and incredibly wide-ranging, talented musician and scholar. He is somebody who I would say can almost literally write about anything to do with music. But the notion of America was interesting because we know that Wagner, later on in his life, thought about emigrating. I wrote to Leon and I said, “There’s this thread we can pull out” and he had so many ideas about where to take (the topic) – in the end, there’s a very important set of sources that he brings to bear. He does a wonderful job of really positioning this ambivalent history in America to race relations with things like Parsifal, German immigration, and The Birth of a Nation. It really was amazing to chase down what is a very textured history that I think we don’t really receive in biographies of Wagner or in normal narratives that accompany performances in program notes and other material. This was an opportunity to find excellent, insightful people and to think harder than we might normally do about the kind of subjects that Wagner in the 2020s warrants in the world as we find it.

Did those subjects for Wagner in Context arise naturally, or did they arise out of the material that you received? Gundula Kreuzer already wrote about the technical side of Wagner’s stagings, and Mark Berry has his book (written with Nicholas Vazsonyi) on The Ring. Was it a grand plan or something more organic?

Like you, I’ve read all of this literature when it comes out, and I was guided by people who’ve made a very significant contribution. To ask, for instance, Katharine Ellis, to write about Paris – there’s almost nothing that Katharine doesn’t know about Paris and Wagner in the 19th century. Her work has developed, of course, and gone in many directions but she is a figure who is just a world authority in this area.

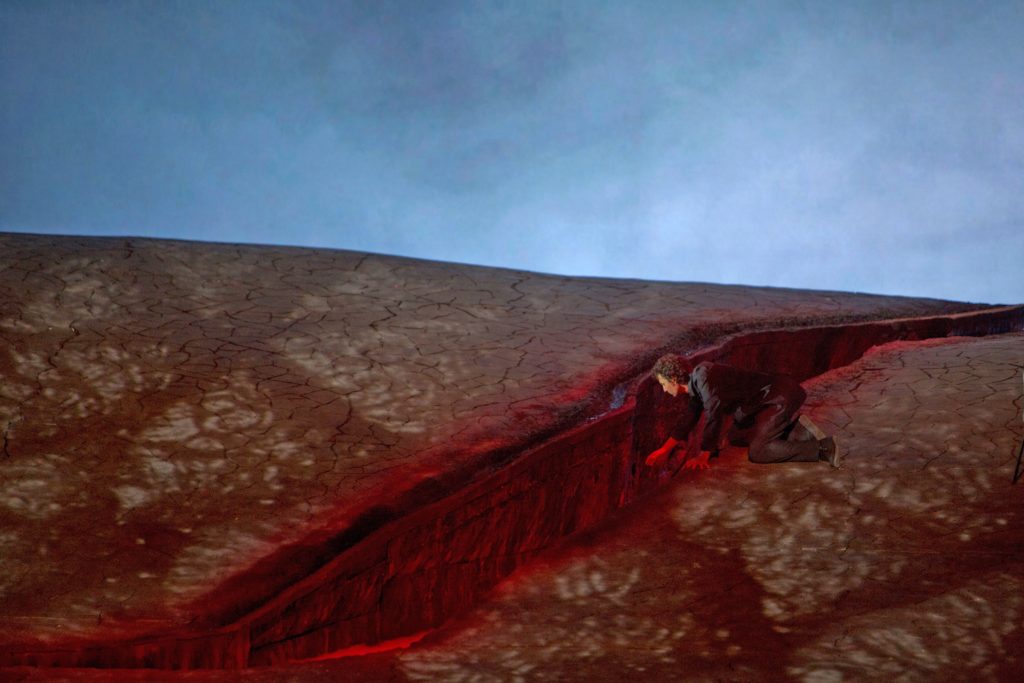

Likewise Gundula Kreuzer is an authority on the stage technology. In her case, because I felt the history of stage technology is just too big, there are three chapters that kind of fit together on that overall topic, so you’ve got Gundula’s history of staging (“Stage Technology), which pretty much goes up to the premiere of The Ring Cycle in 1876; then you’ve got Patrick Carnegy, who picks up the baton just after the premiere (“Historic Stagings: 1876-1976”) and looks at the history of the 20th century staging up to Chereau in 1976; after that there’s a wonderful chapter by Clemens Risi that really looks at performance traditions (“Regietheater in Performance”) and more exploratory and risque presentations; he’s written very thoughtfully about how, for instance, performers and performance psychology are affected by some of the very real challenges the directors throw at them, some really quite undignified visuals that we might think, “Gosh, that’s risqué” we maybe don’t stop to think about how it feels to be a performer, doing a dream role, but being told by a director to do X-Y-Z. And I think that there was a very interesting levelling of perspective there. I suppose if those three chapters are linked one could tack them on to “The Wagnerian Erotics Of Video Game Music” by Tim Summers.

I found that essay particularly fascinating, and very contemporary…

Yes, Summers is a wonderful scholar at Royal Holloway in London. That essay began life as something about internet memes and the way the themes and motifs from The Ring Cycle can bounce around the internet and be repurposed – how they acquire meanings in different video games. Lo and behold, he brings Schopenhauer into a reading of the game player who escapes themselves in the projections they experience within the game, and this becomes “The Wagnerian Erotics of Video Game Music” – it was quite unexpected, but incredibly unique and really insightful. So you can really look at the different configurations, I think.

“Flickering” And Editing

Different configurations, but they speak to something that you write in the introduction, that “the point about contexts is that they start to flicker with insight only when they run deeper than biography.” I thought of this with relation to the Summers essay while simultaneously considering how many might only know Wagner from cartoons or The Blues Brothers, how Wagner himself wasn’t interested in artsy silos – were these sorts of things “flickering” in your mind as editor? And why does do these “flickerings” matter in appreciating an artist like Wagner in 2024?

I think it’s a wonderful question. The way this was initially presented to me was as an opportunity to rethink the relationships between figures that we think we know quite well and some of the deeper history. As historians we’re always looking at the deeper history, but very often we don’t have the chance to write about it as the primary object because it’s only the background, so this is why at the end of that introduction I mention the metaphor that writer José Ortega y Gasset introduces when he’s talking about modernist art.

In 1925 he wrote a book called The Dehumanization of Art (Princeton University Press), and at one point in it he gives the example of looking through a window at a beautiful garden; you can focus on the garden and you can see the beautiful pictures, or you can see the colour used by Kandinsky or some of the textures in a sculpture – or you can look at the frame. You can zoom back and you can actually look at the window frame and see how it’s making the garden a picture. That drawing of attention to the medium was central to what Ortega was saying about modernist art.

For this question of context, I thought, well, that’s exactly what we can do now. We already study the “scene” – of literature from Spain or France or whatever, and we do put our favourite composers into that, but we never actually focus on the framing. So what this book does is give scholars and readers a chance to play with that lens of focus and zoom in on one thing or another and to really ask how Wagner fits into the world of finance, or into the literary culture of Spain, or media theory. There are lots of different elements at play. So yes, “flickering” is the right word because it’s that dynamic sense, a type of motion that is not fixed to where you actually are as a reader or scholar; you have to make the object of your study move, not just try to learn all the details about it as a sort of stone sculpture but make it real for the here and now.

Photo: mine.

How real did it become for you, particularly in light of your work on Liszt’s Sardanapalo? I would imagine that experience changed your own lens with Wagner.

Oh yes.The relationship between Wagner and Liszt has been problematised a little bit in recent years. At the beginning, Liszt had far more fame, wealth and status than Wagner did, but of course that changed. At the end of his life Liszt regarded himself as “Bayreuth’s poodle” – that’s his expression – that he was wheeled out for big events. He felt like he was being used. I think the challenge for historians is to think about, not only at a personal level, what it costs to have this changing relationship to Wagner, but to track the ways in which that was manifest with money. All of these things were there to be documented, but I think the broader question is: what should historians make of these artists now?

Wagner’s music has made him enormous and very widely performed; Liszt’s legacy as a composer remains restricted in a popular sphere, I think, to the keyboard works, and even then, only to a very small handful of keyboard works. We might flip the coin and say, “Well, what about Wagner’s keyboard works?” – because there are keyboard works by him. They were composed after Lohengrin and Tannhäuser. But we don’t talk about them; they’re not a main part of his legacy. I think the question of why we value some music and not others, and why that’s so unbalanced, is an interesting one. Joanne Cormac does a really great job in her essay (“Franz Liszt”) of bringing some of these larger historical options to the fore, and also the biases of our own historical narratives that tend to marginalize Liszt and bring Wagner ever more into the larger sphere.

This was what I was getting at regarding musical marginalizing: Sardanapalo seemed like an attempt at historical balance, among other things.

Well, when Liszt insisted on pursuing an Italian opera, Wagner advised him not to do it – he tried to give him a cast-off libretto and said, “Why don’t you set this to music?”. I think Liszt stuck to his guns and Wagner then said, “Well you should write something in German for Weimar and stop trying to be an Italian composer” – so while I don’t know what he would have said (to the Sardanapalo presentation) I do think your point is absolutely right, that Liszt had a musical talent, the likes of which is hard to imagine. He was so versatile and able to absorb so much from his surroundings. His work ethic was phenomenal if you look at the rate of production when it gets to Weimar. The opera that he spent on and off seven years really working to complete is a testament to his absolute fluency in not only a Bellini and Donizetti style, but the fact that he had absorbed aspects of the orchestrations for Tannhauser and Lohengrin. I think that kaleidoscopic imagination made itself known in an incredible ability to synthesize and draw together threads that seemingly don’t make sense, but actually sound great, and you’re right, it is very important, I think, to hear it. You can’t really understand it theoretically; you have to experience it.

Photo courtesy of David Trippett.

Sensory Relevance… ?

How do you see perceptions of Wagner evolving in the 21st century? What role can (or should) context play in presentation?

I think on the one hand there is a magnetic appeal to Wagner’s music. It is so rooted in what he called “Sinnlichkeit” – an appeal to the senses – that that alone, in the hands of a driven, skilled orchestra and wonderful singers, will create a spectacle and an artistic experience that will always be revelatory. It is not too hyperbolic to state that something like Tristan is a miracle of humanity; the job of performers and directors is to convey that value with the audiences.

I think the question to begin with is: how do we relate something that was composed in 1865? Or relate to The Ring Cycle, which premiered in 1876? How do we present it anew to an audience that can hear it on YouTube? Or that can get any parts of the score for free and are more likely to be involved in pop or any number of different new musical trends? The whole world has changed so much in such a short time – and on the one hand, Wagner’s style and language has an eternal appeal, but on the other hand there’s a very real question as to what one does to update and remain relevant in the here and now. There are many cases of directors not quite getting it right, of being too shocking; there’s the case of a production of Tannhauser in Germany (2013) which had to close after one performance because it was gratuitous in its references to the Holocaust – it didn’t have an organic relation to the opera – and many found it very upsetting.

Where does the word “relevant” fit then?

Well I think we do have to be relevant, but I think being relevant doesn’t mean always drawing on objects in the here and now. A whole genre of opera in the 1920s called Zeitoper was precisely meant to be relevant; they used all of the gadgetry of the times, like telephones and gramophones, and had contemporary themes and allusions to popular music, all aimed at making the art form accessible to audiences. For example, there’s an aria in Hindemith’s opera Neues vom Tage (1929), which praises hot water and gas, and was originally sung by a soprano wearing a flesh-tone suit in a bathtub. But this genre had a very short shelf life – it was relevant only for ten years. I think that is the problem of, you know, being “up-to-date” and being “relevant”; the more up-to-date you are, the sooner you become out-of-date. The challenge is to balance the music’s eternal appeal with things that matter in the here-and-now, and that is, I think, an issue to be solved by each director.