The passing of Dmitri Hvorostovsky didn’t shock me, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t painful. The experience of living with a loved one with cancer for over a decade has made me cynical about happy outcomes, but, my reaction yesterday was less related to cynicism than to the direct experience of seeing the baritone this past April, recalling the last time my mother saw him, and accepting, with a heavy sigh, the finite nature of humans living with terminal illness.

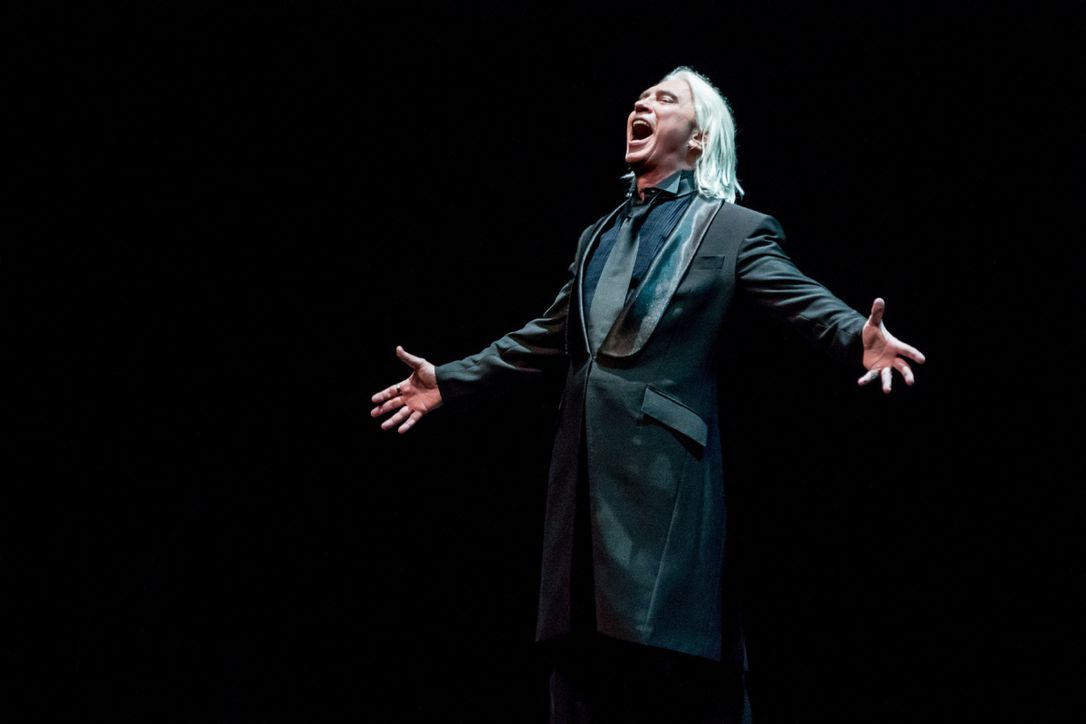

Dima, as he was known by friends and fans alike, sounded magnificent on that cool April evening. Part of a concert event called Trio Magnifiico which marked the Canadian debuts of fellow Russian opera singers Anna Netrebko and Yusif Eyvazov, it was, I later realized, powerful for not only the chosen repertoire (largely by Hvorostovsky himself, as Netrebko had told me in an earlier interview), but for the inherent power of a man clawing at his own fate through his art. The appearance marked Hvorostovsky’s first public performance in several months, following the announcement of brain cancer in 2015. If ever there was an occasion when one could say a man was raging against the dying of the light, April was it. Hvorostovsky didn’t seem sad, but his performance (consisting mostly of Russian repertoire) had the fiery edge of anger, an impulse I remember thinking my mother would have recognized and wholly understood. His body language, especially in one aria (from Rigoletto, an opera about a man struggling against his own dying light, embodied in Gilda, the character’s daughter), expressed rage, sorrow, an intensity of flesh and spirit — of their collision, and the chaos that created. I remember clenching my jaw toward the end of the aria in a vain attempt to prevent tears. (It didn’t work.)

When I learned of Hvorostovsky’s appearance at the 50th Anniversary Met Gala shortly thereafter, I had to smile; I was in Berlin at the time, and I had wondered, with every deep-voiced performance I had heard, “how would Dima have done this?” I wasn’t comparing so much as curious: where would he have taken a breath? How would he have finished that phrase? How would he have approached this role? Why would he have made x or y choice? I equally realized, with many heavy sighs, that I would never see Dima onstage in Berlin, or probably anywhere else, for that matter, again. There’s a bittersweet fatalism that develops when you’ve lived with death for so long, sat across from it at every forced meal, driven with it humming in the backseat to doctor’s appointments, dragged it around shopping malls at the holidays. When it forces you to its logical endpoint, somehow the goodbye feels too soon — too mean, too heartless, and you realize the unfair bargain you were forced to make and live with. It makes perfect sense, and no sense at all. Cancer is grotesque that way, and no amount of fighting language popularly attached to it will ever remove the sting of sudden loss, much less the slow, dull ache of a long one.

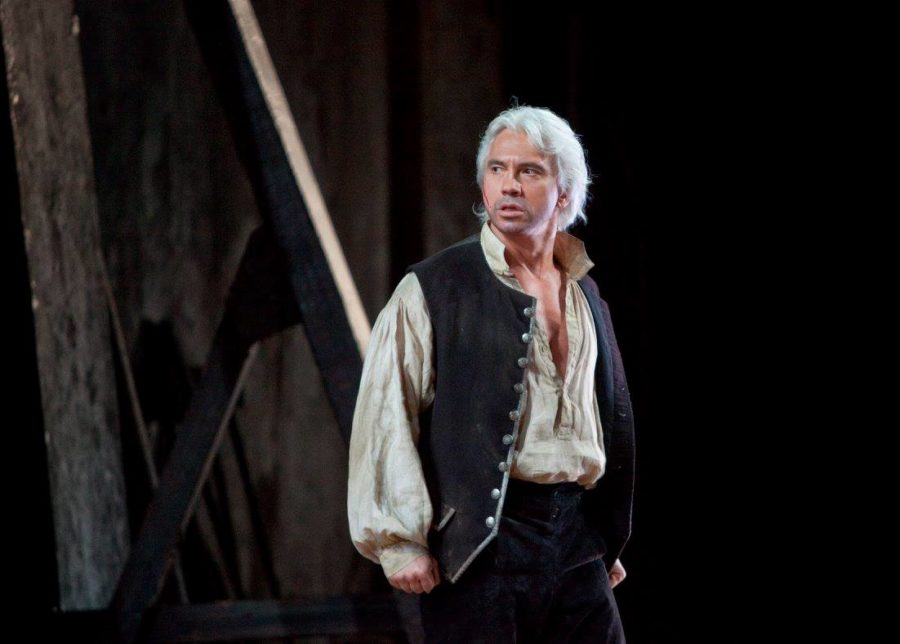

As Simon Boccanegra at the Metropolitan Opera, 2011. Photo: Marty Sohl/Met Opera

And so yesterday, as I attempted some degree of work productivity, I found myself listening to his voice blazing out of my radio, watching clips of him from 1989 (when he won the prestigious Cardiff Singer of the World competition), and being plunged into a deep well of memories, recent and far, fond and bittersweet. In trips to New York, my mother and I saw him in a variety of works, including The Queen of Spades, Eugene Onegin, Don Carlo, Rigoletto, and Simon Boccanegra. One didn’t merely hear his voice or watch him move; one experienced him and the force of his artistry, his confidence, his je ne sais quoi as a whole. It wasn’t just his considerable physical beauty — there are lots of good-looking people in opera, and always have been — but a kind of magic he conjured, contoured, and conveyed in waves. Few and far-between are the times in my life when I’ve sat in an opera house and been thoroughly, utterly thunderstruck by a perfect combination of vocal power, theatricality, confidence, ease, and … what? It isn’t easy to name. Call it star power, call it magnetism, call it presence; Hvorostovsky had it in jar-fulls, but carried it so lightly, like any star should. In a 2006 interview with New York Magazine, he commented that “(t)he sex appeal is part of the package. My voice is sensual, too, and it is part of my image and my character and my personality. It has something to do with a little magic called the “significant presence,” or whatever.”

The velvet-smoke sound of his baritone was every bit as ubiquitous in my house growing up as the silvery tones of a certain famous Italian tenor; if Pav was the soundtrack of my childhood, Dima’s filled the role for my youth. I felt what virility was before I understood it. That sound would make everything stop: thinking, activities, hearts, breath. It commanded attention. He existed firmly within the world of opera, but also without, in an entirely different category, one I think he carried inside of him, guided by his homeland, by family, by the responsibility he felt toward the composers whose work he performed as well as the spirit behind those works There’s a bitter irony to Hvorostovsky passing away on November 22nd, the Feast of St. Cecilia, patron saint of musicians; it’s the day before Pavarotti made his Metropolitan Opera debut (in Puccini’s La bohème), in 1968. The sad realization that two of my mother’s very favorite singers, both of whom I saw live on multiple occasions, were taken by the same disease that took her, has forced some painful contemplations, though she’d remind me not to be so morbid, to simply “think of the music!”

The last time my mother and I saw Dmitri Hvorostovsky live together was at a 2014 recital at Koerner Hall in Toronto. My mother was suffering the horrendous effects of her umpteenth round of chemotherapy, and worried she wouldn’t be able to use the (great) tickets I’d hastily bought the day they went on sale months before. But something — her music passion, love of his work, curiosity, happiness to escape the house, worry at letting me down (or a mix of everything) — propelled her. I remember dropping her off along a bustling Bloor Street; she waited on a shady bench as I parked and ran back to meet her, trying to hide how rotten she felt, how tired she was, how fragile and thin she’d become. We slowly made our way through the venue, and she clutched her program as she carefully lowered herself into her seat. Trying to describe her face as Hvorostovsky stepped onstage is still impossible; I only remember her being lit from within. Over the next two hours, something happened: suffering stopped, disease stopped, the horrible daily details of illness stopped. There was purely sound, presence, pull — of being with Hvorostovsky through every breath, pause, roar, turn, smile. closing of eyes. We were with him.

At the Four Seasons Centre For The Performing Arts as part of Trio Magnifico, April 24, 2017. Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov / Show One Productions

I felt this once again in April, and I remember it now. Watching Hvorostovsky, I am in that world where everything stops; death gets out of the car, steps away from the table, is rendered powerless. It is magic.