At the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

Before my most recent trip to Berlin for my birthday in earlier this month, I quickly jotted down a few music events that stood out to me without thinking too hard about the whys or wherefores. There have been so many special moments, and it’s hard to squish them into a list, let alone words and descriptions, and sometimes too much analysis not only muddles decent reflection but kills the joy of remembrance.

Many year-end “favorites” lists that show up this time of year tend to be steeped in memories and sentiment, and music is the best and most direct avenue to both. As music writer Tim Sommer points out in his own year-end feature, “no art form is as connected to our memory and our senses as music. Although music appears to exist primarily in just one of the senses, in fact it spreads to all of them, creating a connection with everything we were seeing, touching, smelling, and thinking.”

So much of my life is made up of lists — for packing, for groceries, for trips, and for stories to chase and features to finish. If I could write a list of feelings throughout the year the way I quickly wrote out my list of music experiences, how would it read? Disappointment might feature largely, but so would wonder. With a second near-solo Xmas Day under my belt, a lot of time has been spent in remembrance, on events recent and not, and on people new and old, near and far, present and not. In returning to my music list, muddling through the sometimes sticky waters of sentiment and memory, and ruminating on the ease of my choices, I’ve come to realize that wonder is the ribbon tying everything together. It’s a quality I fully realize can’t be forced, but can, perhaps, arise out of the right set of conditions. It logically follows then, that next year I hope to be writing this list from Europe. (You read that correctly.) Until then, please enjoy, and feel free to add your own favorites in the comments.

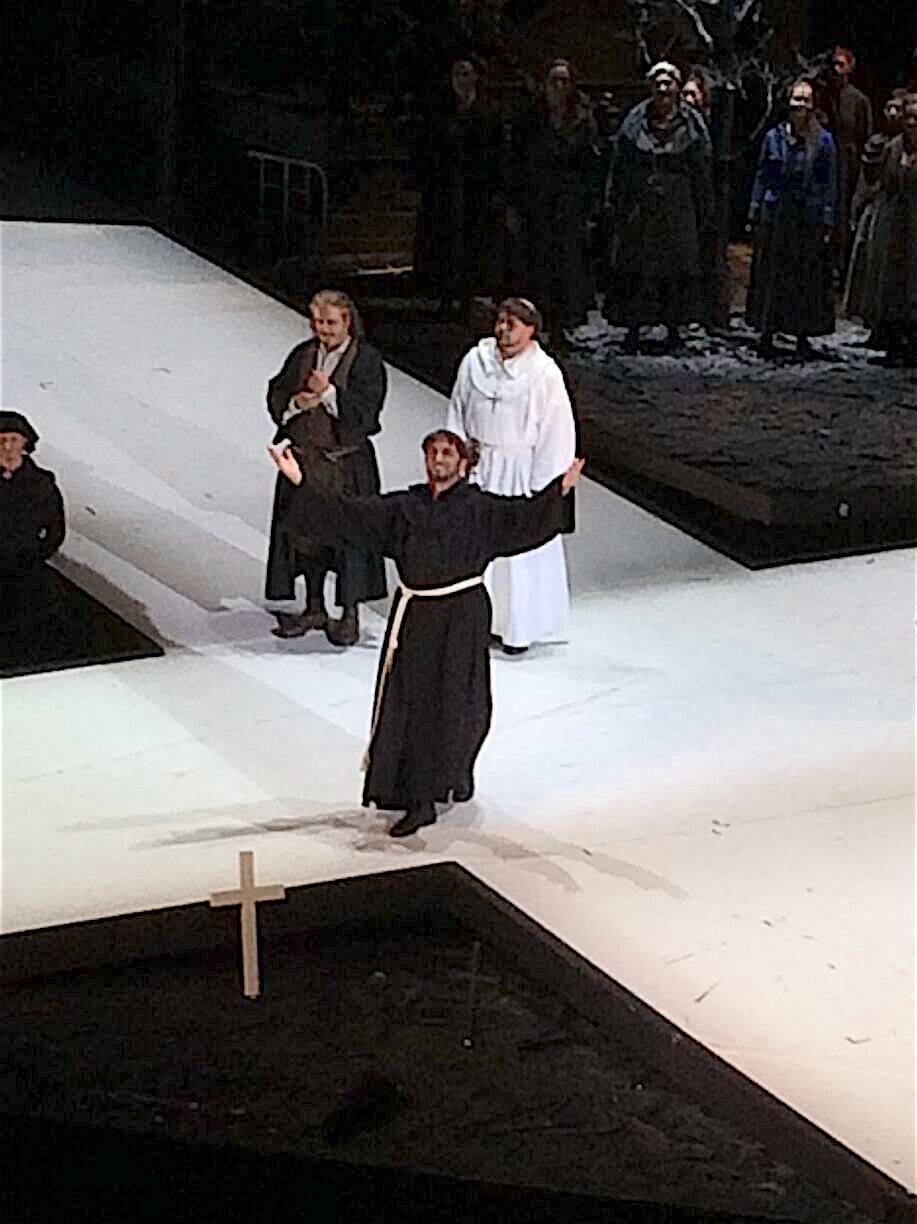

The cast of “La damnation de Faust” take bows at the Opera Royal de Wallonie (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

1. La damnation de Faust, Opéra Royal de Wallonie; Liège, January.

Though I have loved the work of Berlioz for years, never have I heard it so vividly and lovingly brought to life as here, in the beautiful, ornate opera house of lovely Liège. American tenor Paul Groves, currently onstage at the Met in The Merry Widow (my interview with him here), turned his Faust strongly away from tormented-hero cliches and into something recognizably (and touchingly) human; his chemistry with Ildebrando D’Arcangelo’s Mephistopheles was warm, watchable, and quietly splendid. (More here.) Together with Director Ruggero Raimondi’s thoughtful production and strong orchestral vision from Music Director Patrick Davin, this was one of the best ways to start the musical new year.

2. Il matrimonio segreto, Opéra national de Lorraine; Nancy, February.

Conductor Sascha Goetzel led a vivacious reading of Cimarosa’s frothy and very Mozartean score (on the day of its 225th birthday, when I attended) in this fun production of the 1792 opera by Cordula Däuper in Nancy’s sumptuous opera house. Standouts included tenor Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani as the lovestruck Paulino, baritone Riccarado Novaro as seeming-fop Conte Robinson, and jovial baritone Donato Di Stefano as the bumbling Signor Geronimo. They, along with the entire cast, skillfully used Sophie du Vinage’s zany costumes and Ralph Zeger’s comical dollhouse sets to wondrous effect, embodying the very best sitcom stars with boundless energy and zesty, charismatic stage presences to match. This was “Three’s Company” 18th century style, complete with beautiful music and cartoon costumes — and it was fantastic.

Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde and Andreas Schager as Siegfried in the Canadian Opera Company’s production of “Gotterdammerung.” (Photo: Michael Cooper)

3. Götterdämmerung, Canadian Opera Company; Toronto, February.

Christine Goerke, who sang the role of Brünnhilde in this modern production, is one of the very great singers of our era, and you should run, not walk, if she’s performing in your town. This lady (my interview with her is here) understands, at a deep level, what makes Wagner (and music) exciting, affecting, and fiercely human. If ever you’ve said ‘I don’t like Wagner” or “I don’t understand opera” or “Opera is boring,” she is the person who will guide you to a place that may change your mind. This was her third turn in Toronto singing as part of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and with each performance, including the one last winter, her Brünnhilde grew ever more alive and vivid. Goerke is truly a gifted vocalist and a great performer, and in this final instalment of the immense Ring Cycle, she infused every scene she was in with an earthy, robust presence. In a word: magic.

The set of Willy Decker’s “La traviata” at the Met in New York. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

4. La traviata, Metropolitan Opera; NYC, March.

I have seen this opera many, many times in my opera-going life, but never have I seen one with more unusual characterizations. It forced a rethink of every single trope I had taken for granted. Alfredo, the male lead, was not a lovelorn romantic figure, but an obsessive weirdo bordering on abusive. Tenor Michael Fabiano captured every nuance of the character with magnetic clarity, and he was matched here, beautifully, by baritone Thomas Hampson, whose Giorgio was desperate, mean, and possibly more abusive than his son. It was a remarkably theatrical approach, and it was gripping to watch the two interact with Sonya Yoncheva’s sad, exhausted Violetta, a woman so desperately at the end of her rope she overlooks the character flaws of the men who constantly surround her. I had my reservations of Willy Decker’s production overall (more here) but I loved the central performances, and still think of them with awe.

Colin Ainsworth and Peggy Kriha Dye in “Medea” at Opera Atelier. (Photo: Bruce Zinger)

5. Medea, Opera Atelier; Toronto, April.

As with La traviata, the strength of the performances in Medea are seared into my memory. (My review here.) Tenor Colin Ainsworth embodied the wayward husband character with bravado, his Jason conniving, sexy, sensuous, and highly manipulative, always managing to say the right thing while shamelessly doing wrong, less a libidinous cartoon than a recognizably entitled man brought low by the slow-boiling rage of Peggy Kriha Dye’s titular sorceress. Their scenes together sizzled with an intense love-hate chemistry that so clearly reminded one of the all-too-human basis of mythology; these characters of yore may have odd names and be entangled in crazy-seeming stories, but Atelier’s production of the Charpentier work, for all its beautiful design elements, offered an important reminder that the human heart is a very messy and frequently painful place.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky as part of Trio Magnifico. (Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov / Show One Productions)

6. Trio Magnifico, Toronto; April.

The concert marked both the Canadian debut of soprano Anna Netrebko and tenor Yusif Eyvazov, as well as the final Canadian appearance of baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky. (My tribute to Dima here; my interview with Netrebko and Eyvazov here.) With the Canadian Opera Company orchestra led by Jager Bigiamini, the famed trio performed a Russian-heavy program that also featured several standard opera favorites, including Hvorostovsky’s anguished, heart-rending performance in a scene from Rigoletto. People can (and have) roll(ed) eyes that it was a concert about frippery and hype, that it lacked substance and/or deep artistry; everyone is entitled to such opinions. But for me, it was a concert where music became very real, where hearts were shamelessly worn on sleeves (and fancy dresses), and where the electric thrill of world-renowned voices was finally felt in a city that had waited too long for such a large-scale opera event. Bravo (and more of this, please).

At the Konzerthaus Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

7. Herbert Blomstedt with the Vienna Philharmonic and Kit Armstrong, soloist; Konzerthaus Berlin, May.

Armstrong gave a beautiful, loving reading of Beethoven’s famous Third Piano Concerto, in a program that also featured Bruckner’s Fourth symphony. This concert was part of a series of programs dedicated to (and saluting the work of) pianist Alfred Brendel, and there was, I think, no better way to pay homage. The American artist didn’t pound the crap out of the keys or show off his Mad Finger Skillz the way some young soloists are prone to doing; rather, in perfect harmony with Blomstedt’s delicate direction of a creamy (if highly textured) Vienna Phil, Armstrong coaxed the gentle splendour out of the fiendishly deceptive work with kindness, gentleness, and a profound sense of poetry. The focus was always very squarely on the music, as the audience at Konzerthaus so expertly proved with their careful, intense listening and, at the concert’s end, continuous applause and (rare for Berlin) standing ovation.

The cast of “Die Krönung der Poppea” take bows. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce.)

8. Die Krönung der Poppea / Ball im Savoy Komische Oper Berlin, May.

If you’ve spent any time around me this year, chances are very good you’ve heard me rapturously talk about this, and probably more than once. To be plain: this updated version of The Coronation of Poppea was one of the best experiences in my entire opera-going life. Monteverdi’s score was infused with creative, modern, character-focused touches, thanks to Elena Kats Chernin’s ingenious instrumentations, and Katrin Lea Tag’s sexy, sparse design, together with Barry Kosky’s seriously smart direction, confidently underlined every bit of timeliness inherent to the work. This was sex, blood, murder, madness, power, set to repeat, and to a bang-up smashing soundtrack. The Komische Oper’s easy pairing of what could be called “high classical” works (like those by Monteverdi) with fun, frothy pieces like Weimar Republic operettas (i.e. a sassy, very funny production of Paul Abraham’s Ball at the Savoy, featuring the great Dagmar Manzel) highlighted the eclectic, culturally diverse performing arts scene in the Berlin opera world. This is a company (my write-up on them here) that understands the role both opera and operetta play in a healthy music ecosystem, and they do both with incredible style and smarts.

The cast of “Der Rosenkavalier” take bows at the Metropolitan Opera. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

9. Der Rosenkavalier, Metropolitan Opera; NYC, May.

Not only did this mark a goodbye (of sorts, maybe) for soprano Renée Fleming, it was also one of the most satisfying productions that has graced the Met stage in a very long while. Robert Carsen balanced every element with grace and panache, placing the story (about genteel Viennese in a battle of hearts and minds, of sorts) in a pre-WW1 setting, giving both the narrative and infusing its cast of characters with poignancy. The chemistry between Fleming and Elīna Garanča, in the pants role of Octavian, was gripping, magical, and very palpable. (More of my thoughts here.) We don’t have to guess at Octavian’s fate here; it isn’t, as so many productions might have you believe, happily-ever-after. Never has stripping the saccharine veneer off Viennese finery been more satisfying, or dare I say, beautiful.

Marcelo Puente as Cavaradossi and Adrianne Pieczonka as Tosca in the Canadian Opera Company production of Tosca, 2017. (Photo: Michael Cooper)

10. Tosca, Canadian Opera Company; Toronto, May.

Mesmerizing stage presence, an imposing physique, a luscious tenor sound – this production could have well been called “Mario” for the heat Marcelo Puente brought to it. (My interview with him here.) The Argentinian tenor exuded star power in waves, even as he maintained perfect vocal control and demonstrated a deep respect for Puccini’s buttery score, his rendering of the famous “E lucevan le stelle” a clear cry out of spiritual and emotional darkness, dramatically rich as it was vocally fulsome. The chemistry Puente shared with leading lady Adrianne Pieczonka was notable for its casual ease; this was a Tosca and Mario who were clearly friends as well as lovers, something refreshing in an opera usually overstuffed with giant romantic gestures that don’t always feel sincere. This did.

Vladimir Spivakov and Hibla Gerzmava with the Moscow Virtuosi in Toronto. (Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov for Show One Productions)

11. Hibla Gerzmava in concert, Roy Thomson Hall; Toronto, June.

Despite some apparent throat issues, Gerzmava gave a beautiful concert with the Moscow Virtuosi, providing a splendid introduction for Canadians unfamiliar with the soprano’s incredible range and repertoire. (My review here.) What struck me watching Gerzmava live was how easily she moved between modes: diva, philosopher, dreamer. Some opera performers have one mode, which they only slightly alter between pieces and roles, and that’s fine too — every artist is a little bit different, an they do what works best for them, in the moment and for the long term — but Gerzmava melted into every single thing she sang, one moment teasing Virtuosi performers, the next, falling beautifully into a French aria. Her clear commitment to the variety of chosen repertoire was matched by a quicksilver tone and a gracious stage presence that made me keen to see her live onstage again soon.

RIAS Kammerchor at St. Hedwig’s. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

12. Berliner Festspiele; September.

Autumn saw a quick if very busy trip to the German capital to cover concerts and performances at the annual arts event for Opera Canada magazine (published in their next edition in early 2018). A standout from the Fest includes the RIAS Kammerchor, led by Justin Doyle. Together with period instrument ensemble Capella de la Torre, the choir marked the 500th birthday of opera forefather Claudio Monteverdi by performing a series of day-spanning concerts at both the historic St. Hedwig’s Cathedral and the modern Boulez Hall; the contrast was stark and beautiful, and very haunting. (My review here.) Also memorable was the Korean Gyeonggi Philharmonic Orchestra, who offered a program chalk-full of works by Isang Yun, a Korea-born German composer whose 100th birthday year was being marked with events throughout the Festspiele. The Konzerthaus audience at the Sunday morning concert responded with incredible passion and offered beautifully careful listening as conductor Shiyeon Sung led her very elastic orchestra on a very gripping sonic journey.

Roberto de Candia as Falstaff in Parma. (Photo: Roberto Ricci)

13. Falstaff, Teatro Regio di Parma; October.

Go outside the Teatro Regio and into the streets of Parma, and I guarantee you would have found any of the characters featured in Jacopo Spirei’s smart production of Verdi’s classic, based on the (in)famous Shakespeare character. (My interview with Spirei here.) This was a presentation that got every element right, from design to blocking to performances, while leaving great respect for the challenging if fiercely sparky score. Roberto de Candia was brilliant as the titular Falstaff — not a fun-loving-fat-man cliche, but a vulgarian bordering on loathsome, who was only redeemed by the strength and grace of the women around him. This wasn’t merry old England but dirty old Blighty and it was brilliant — and a troupe of English travellers I met at intermission heartily agreed, adding it was the best thing they’d seen at the Festival Verdi this year. (I agree.) I really hope this production travels to North America at some point; it has so much to say, and says it in such a smart, and frequently funny way.

Dominik Köninger with the Deutsches Kammerorchester Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

14. Dominik Köninger in recital with the Deutsches Kammerorchester Berlin, Kammermusiksaal der Philharmonie Berlin; Berlin, October.

In seeing Die Krönung der Poppea, I wrote that the German baritone delivered a “snarling, sexy, utterly magnetic performance” as Nero, an observation perhaps made more poignant for it being one of the few darker roles he has done. Köninger is, as he told me over the course of a subsequent interview (link), usually cast in what could be considered good-guy roles like Papageno, Orpheus, Figaro, and lately, Pelléas. Perhaps he should consider adding more villains — or at least more darkly tormented figures. Köninger’s propensity and talent for deep, dark, yearning repertoire was shown to full effect in a concert given just before Halloween at the Philharmonie’s Chamber Concert Hall with the Deutsches Kammerorchester Berlin. Titled “Totentanz” (or “Death Dance”), the program was a smart, carefully curated mix of Grieg, Purcell, Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Schubert, and Mahler; it also featured gripping instrumental selections and abridged scores from various films (including Psycho), rearranged for strings. This was a concert that transcended the corny, faux-scary Halloween tropes and went straight to the heart – of darkness, isolation, longing, claustrophobia, sadness, desolation — and showcased Koninger’s coppery-toned baritone. Mahler’s “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (“I am lost to the world”) and selections from Schubert’s Winterreise were true highlights, performed with exquisite soulfulness. Forget the good guys!

“Nabucco” at Deutsche Oper Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

15. Nabucco, Deutsche Opera; Berlin, November.

People who know opera have lots of opinions about this work (it’s too long; it’s never done right; it’s too narratively meandering) but everyone, opera fan or not, knows the famous Hebrew Chorus (“Va pensiero”). Unquestionably, that’s just what some of the Deutsche Oper crowd was there to hear this past November, holding collective breath until it unfurled, note by majestic note, under the careful baton of conductor Roberto Rizzi Brignoli. Still, there was an overall curiosity and appreciation of the intriguing staging and strong singing. The audience was confronted with an uncomfortably familiar world where deep polarization was sewn by the brutality of fervent nationalism and intolerant religiosity. This spicy timeliness was underlined by Anna Smirnova’s magnetic performance as Abigaille, Nabucco’s doomed daughter. Director Keith Warner denied audiences the sentimental mood (and ending) which is sometimes presented in productions, instead presenting a world where tenderness is rare, and highly dangerous. The “walls” of Tilo Steffens’s immense set shut before the doomed Abigaille at the close; there was no forgiveness for her trespasses. It was a devastating, disturbing, and frankly, fantastic conclusion to a challenging production of a work too often soaked in sentimentality and star power.

Katrin Wundsam and Elsa Dreisig as Hänsel and Gretel at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin. (Photograph: Monika Rittershaus)

16. Hänsel & Gretel, Staatsoper Unter Den Linden; Berlin, December.

Director Achim Freyer is known for his vivid designs, painterly approach, and almost cartoon-like visual sense, and I was very curious as to what he’d do with the beloved (and widely produced holiday standard) Hänsel und Gretel. No sooner did the music begin and I found myself utterly besotted by the whimsical effect in the famous Humperdinck work. The lost pair were rendered as living dolls, complete with giant eyes (which performers cleverly moved with well-placed levers) and charming, child-like gestures. The Gingerbread Witch didn’t have an actual face, but rather, an enormous, beckoning finger as a sort of stand-in “nose” (complete with a long, red fingernail) , a coffee pot “head,” and various bits and bites of food and goodies making up the rest (think Pizza The Hut, but with less gross factor and far more style). Together with Freyer’s captivatingly creative design, wonderful performances (including tenor Jürgen Sacher as the very campy witch), and strong orchestral coloring (thanks to conductor Sebastian Weigle), the essential tension of the original Grimm fairy tale (abundance vs. poverty) was underlined in large, small, and entirely unmissable ways. It was also special to have this opera be my first experience in the gorgeously renovated Berlin State Opera theatre — talk about a delicious birthday treat!

Christian Thielemann and the Berlin Philharmonic with the Rundfunkchor Berlin and soloists. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

17. Christian Thielemann with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Rundfunkchor Berlin, Philharmonie Berlin, December.

I’m being perfectly honest when I write that conductor Christian Thielemann scares me — perhaps it’s the intensity, or that he reminds me of a few too many scowling band leaders from my high school days. Whatever the case, he didn’t need to smile or be cuddly to lead an astounding Berlin Phil through a non-stop, barn-burner performance of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. Thielemann missed no chances to do the boom-bang version of Beethoven, but he also took time — lots of it — exploring, dare I say, the work’s many luxurious, foreplay-like moments (which sounds bizarre, since it is formally a religious piece, but!). The careful leanings into phrasing, the pregnant pauses, the fine drawing-out of vocal lines tenderly at one moment and whittling away strings and percussions into nothingness at others… some performances leave you (me) breathless, and this was one. When he held the rich, pregnant silence at the end, for several moments, no one in the Philharmonie breathed, or dared to; Thielemann has that effect. It was a very special and memorable way to experience the music of Beethoven at the Philharmonie for the first time — and again, was a special gift for my birthday week in Berlin.

18. Märchen im Grand Hotel (Fairy Tales from the Grand Hotel), Komische Oper Berlin, December.

Talya Liebermann and Tom Erik Lie in “Märchen im Grand Hotel” at Komische Oper Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Robert-Recker.de)

Despite my lacking linguistic facility in German (which I intend to rectify in 2018), the production, with fantastically energetic conducting by Music Director Adam Benzwi, was totally understandable with its themes of sacrifice, acceptance, and change being the only constants in life. The assorted cast of animated characters were brought to vivid life by a dedicated ensemble dressed to the nines, with voices to match; soprano Talya Lieberman and baritone Tom Erik Lie were special standouts for capturing such lovely delicacy in their numbers. Another Grand Hotel-themed musical (the Tony Award-winning 1989 version) is being presented this coming season at the Shaw Festival (in southern Ontario), and I’m planning on a longer feature about this work’s various iterations in 2018, the staying power of Baum’s novel, and what it means for us in the here and now. Please stay tuned? More music adventures are afoot, though hopefully “close to home” will have a different meaning at this time next year.

Tori Wanzama is a new contributor. Her first opera was, in fact, my own introduction to the art form, at the age of four in what was then called the O’Keefe Centre in Toronto. It’s a bit too easy to close ears and heart to something that’s sat in one’s consciousness for so very long, and which is also a tremendous part of the cultural milieu; it is just as much of a challenge to re-open one’s mind to such a relentlessly (brilliantly) melodic work when one is constantly surrounded (by choice as much as necessity) by things so unlike it. And yet, Tori’s enthusiasm and creative insight all work together here to provide fresh, new ground – for me, as much as for those who feel too deeply rooted in classical cynicism. What can possibly grow in such highly acidified soil, after all? Tori’s writing gives opera newbies a bit of needed encouragement toward exploring an art form they (as she rightly outlines) might have their own preconceptions about, and also gives old cynics (alas) a new breath of the curiosity that felt so important to these pursuits in the first place. Reading her words was akin to seeing an old friend after many decades; all the old animosities simply departed. Tori is a second-year Communications student and has, as you will read, an incredible talent for the observation of stagecraft, as well as the nature of opera fandom itself. I look forward to publishing more of her work here in future.

Tori Wanzama is a new contributor. Her first opera was, in fact, my own introduction to the art form, at the age of four in what was then called the O’Keefe Centre in Toronto. It’s a bit too easy to close ears and heart to something that’s sat in one’s consciousness for so very long, and which is also a tremendous part of the cultural milieu; it is just as much of a challenge to re-open one’s mind to such a relentlessly (brilliantly) melodic work when one is constantly surrounded (by choice as much as necessity) by things so unlike it. And yet, Tori’s enthusiasm and creative insight all work together here to provide fresh, new ground – for me, as much as for those who feel too deeply rooted in classical cynicism. What can possibly grow in such highly acidified soil, after all? Tori’s writing gives opera newbies a bit of needed encouragement toward exploring an art form they (as she rightly outlines) might have their own preconceptions about, and also gives old cynics (alas) a new breath of the curiosity that felt so important to these pursuits in the first place. Reading her words was akin to seeing an old friend after many decades; all the old animosities simply departed. Tori is a second-year Communications student and has, as you will read, an incredible talent for the observation of stagecraft, as well as the nature of opera fandom itself. I look forward to publishing more of her work here in future.