Easter weekend is finally here. Whether you plan on indulging in chocolate eggs and hot-cross buns (or not), the current moment is really an ideal time for pondering. The notions of suffering and loss seem very close at the moment. Good Friday is a particularly profound day for quiet reflection. Along with recommended listening, I suggest spending the day with hot tea, soft light, and a bit of reading.

Realities

First up: the UK Musicians’ Census reveals the extent of gender inequity in the British classical music scene. Surveying 6,000 UK musicians, the findings are not surprising but they are depressing. The acknowledgement of ageism is certainly interesting (I’d like a more extensive study focused on Europe as a whole), and the results around financial realities for women are equally pointed. As The Strad reported (March 27):

The average annual income for a female musician was found to be £19,850, compared to £21,750 for men – meaning women earn nearly a tenth less.

Women also only make up just 19 per cent of the highest income bracket of those earning £70,000 or more from music each year. […] The data on the pay gap comes despite the fact that women musicians are qualified to a higher level than men.

This lack of balance was addressed recently by bass baritone Sam Taskinen in conversation with Van Musik‘s Anna Schors (March 27), in which the singer shares her challenges within the opera world as a trans person. Along with exploring aspects of vocal technique and auditions, Taskinen states that what is really needed within the industry is “many more women in leadership positions at the opera houses. In the artistic directorate, as general music directors”, adding that “we need a much greater diversity of people who have responsibility behind the scenes. The problem is not so much that those responsible have no good will. It’s just that some of them have a lot of blind spots.” This reminds me very much of what tenor Russell Thomas said in an interview with me in 2019, that meaningful change within the industry will only happen off stage and within administration; that what is seen onstage is often mere optics, with little if any meaningful transformation powering it.

Report on Business editor Dawn Calleja added meaningful context to this idea of change-through-management in a recent feature for The Globe and Mail (March 28) in which she updated a story she’d done on retail giant Aritzia, and their own challenges in terms of diversity and leadership:

One woman succeeding at an organization does not automatically mean it is welcoming to and respectful of all women.

And that’s the problem with today’s diversity discourse. Sometimes we can get lost in the data and forget the most important part: making sure women and people of colour stick around, and are given the chance to participate fully in and contribute to the corporate culture. Hiring, in other words, is just the start of the journey.

Ruminations

Reading these items I was reminded once again of composer/writer Moritz Eggert’s recent post for NMZ’s Bad Blog Of Musick (March 13), in which he mused on the challenges of cultural presentation in 2024. Opera/classical leadership is trying to navigate a range of pressing issues, including diversity and access, both onstage and off. Eggert uses the mythological figures of Scylla and Charybdis to explore arguments made by the political left and right around creativity and its manifestations, particularly within the operatic realm. Using various readings of the 1978 film Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, Eggert writes that “It is precisely this openness to interpretation and multiple readability that makes great works of art.”

I agree with much of what he writes, but I am still very unsure as to whether or not the sides to which the author refers are actually equal. Whenever I hear (or read) the phrase “artistic freedom” I also sometimes hear (see) “financial incentivization” and/or “unquestioned validation”. Imagining a work which sits outside the realm of one’s immediate knowability raises important questions as to how much of gender, race, spirituality, and nationalistic identity are individually or collectively used as exoticized costuming as opposed to actual reality. Can creators grasp lived experienced through an imagination which has been wholly shaped by their own immediate socio-cultural worldview? Should they try to? Should audiences be asked to go with them? And – crucially – should artists be officially funded for that pursuit? Should audiences pay for it? Or should there be outright denial across the board? Who decides? And in whose interests?

Natasha Tripney, International Editor of The Stage, recently published a fulsome account on various forms of censorship in theatre communities based in Hong Kong, Hungary, Slovakia, the Balkans, and Belarus; if there’s anywhere the (overheated, algorithmically-juiced) term “cancel culture” works, it might well be these places. Her examination has tremendous bearing on the opera world, especially in terms of content and context – the place in which a work is presented, its cultural norms and demographics, are inexorably tied to governing powers and their control of the purse strings. Any contemporary discussion of art and creative freedom, no matter how idealized, which doesn’t mention funding is worth questioning, at the very least.

Speaking of which: many European houses have announced their 2024-2025 seasons and from most indications it looks like Euros will be flying around – and, they clearly hope, through the front doors as well. Opera national de Paris is featuring Offenbach’s Les Brigands as its first new production of the season, led by operetta king Barrie Kosky and conducted by Michele Spotti. Paris’s Opéra Comique has its own fascinating October offering, a staging of Sir George Benjamin’s fairytale-like Picture a day like this, led by the composer himself. Opernhaus Zürich is presenting Leben mit einem Idioten, Alfred Schnittke’s satirical 1992 opera, to be staged by Kirill Serebrennikov and conducted by Jonathan Stockhammer. In November, Dutch National Opera presents Le lacrime di Eros, a very unique-sounding project which will feature both Renaissance and electronic sounds. Romeo Castellucci is director and dramaturg; the work will be led by Raphaël Pichon and include his acclaimed Ensemble & Choeur Pygmalion. Next summer Bayerische Staatsoper presents Fauré’s only opera Pénélope by Andrea Breth and conducted by Susanna Málkki; the work is making its debut with the house, and the premiere on July 18 will be broadcast live on BR Klassik (radio). Also worth noting: new Ring Cycles being set in motion in Munich, Paris (Ludovic Tézier will be their Wotan) and Milan.

Sooner than that: Opernhaus Zürich is presenting two complete Ring Cycles this May, a revival of Andres Homoki’s 2022-2023 stagings and led by house GMD Gianandrea Noseda. Wagner’s super-epic is also currently wrapping up at Berlin’s Staatsoper unter den Linden, also a 2022 presentation, this one by Dmitri Tcherniakov and conducted by Philippe Jordan.

Remembrances

The classical world has lost many greats this month, including Canadian director Michael Cavanagh, who was artistic director of Royal Swedish Opera (RSO). Cavanagh was very beloved in his home country and abroad, with the Manitoba Opera, Vancouver Opera, San Francisco Opera, and RSO all posting tributes to the unique and widely-loved artist, who died on March 13th at the age of 62 . My obituary for The Globe And Mail, featuring quotes from Cavanagh’s family as well as Edmonton Opera artistic director Joel Ivany, is here.

Composer Aribert Reimann passed away on March 13th at the age of 88. His 1978 opera Lear, based on the Shakespearean play, was commissioned by and subsequently premiered at Bayerische Staatsoper; the company posted a beautifully thoughtful tribute at the announcement of his passing. The recording of the work’s premiere, led by Gerd Albrecht and released in 1979 on Deutsche Grammophon, is a cultural touchstone; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s baritone cuts like a knife, delivering the full measure of the work’s tragedy in every careful, anguished note. I spoke with Gerald Finley not long after he’d finished performing the role himself in Salzburg in 2017, and at the time he called it “a fiendishly difficult piece of music”, adding that Fischer-Dieskau’s recording was a real source of inspiration even before he began preparing for the role. (It was Fischer-Dieskau himself who urged the composer to write the work back in 1968). Reimann himself said the opera explores the “isolation of man in total loneliness, exposed to the brutality and questionability of life.”

Composer Peter Eötvös passed away on March 24th at the age of 80. His deep talent for dramatic writing was expressed through his fourteen operas, which include Tri Sestri (Three Sisters), based on Chekhov’s play (1998), Angels in America, based on Tony Kushner’s play (2004), and Love and Other Demons, based on the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (2008), along with Die Tragödie des Teufels, commissioned by and premiered at Bayerische Staatsoper, who posted a remembrance. Eötvös’s 2011 Cello Concerto Grosso really caught my attention – the conversational nature of this piece, the kinetic give-and-take rhythms between soloists and orchestra, is hypnotizing. Eötvös remarked about the work (at his website) that “My concerto is a series of short dance-acts, it well may be that the “last dance” is coming from a traditional Transylvanian culture which is doomed to a slow disappearance….” The work was most recently performed by the Bremen Philharmonic and cellist Sung-Won Yang, and led by conductor Jonathan Stockhammer.

Pianist Maurizio Pollini, who passed away on March 23rd at the age of 82, was known and rightly celebrated for his recordings of Chopin, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg, and post-modernist composers Boulez, Nono, and Stockhausen. His Deutsche Grammophon recordings of the Beethoven sonatas were so central to my younger, intensely-piano-playing days. I was especially drawn to his 1989 recording of numbers 17, 21, 25, and 26 – the quiet, unshowy poetry; the slow, intense drama; the easy mix of grace and control; the clear sense of line running through and connecting it all. “My feeling is exactly the opposite of controlled,” Pollini told the Chicago Tribune in 2004, in an attempt to bin an undeserved “cold intellectual” label. I returned to those Beethoven recordings (and more besides) at learning news of his passing last weekend. Pollini’s performance of the second movement (Adagio) of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 17 In D Minor, Op. 31, still has the power to make me drop everything and stop, breathe, listen, 35 years after first hearing it.

In closing: New York’s wonderful Rubin Museum is presenting its final exhibition, at least within its physical space on West 17th Street in Manhattan. (It’s about to go digital-only.) Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now, running now through October 6th, explores contemporary art from the region through a variety of media, including sound, sculpture, video, painting, installations, and performance. The exhibition showcases the work of 32 contemporary artists alongside a variety of items from the Rubin’s collection. New and old, engaging in fruitful dialogue; imagine that.

Happy Easter wishes to those celebrating. Remember to use the c-word in your Sunday dinner conversations. (That would be context.)

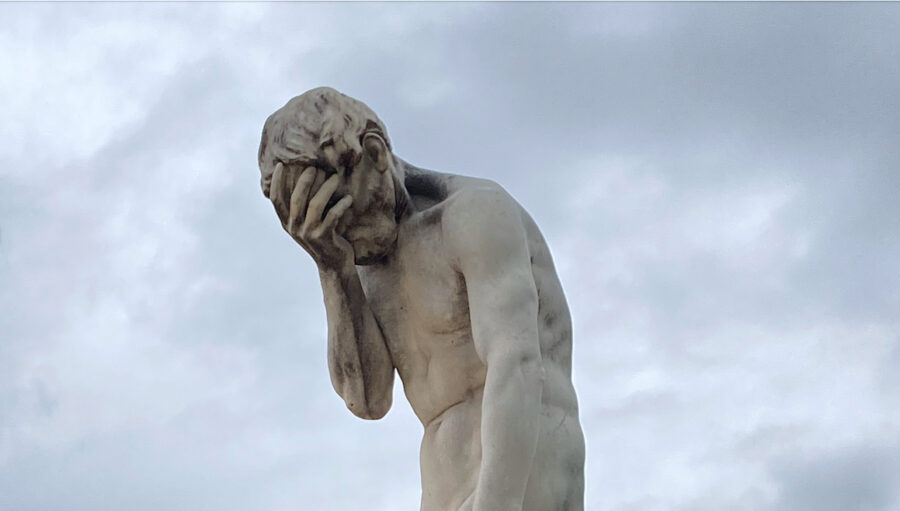

Top photo: Henri Vidal, Caïn venant de tuer son frère Abel, 1896; Jardin des Tuileries, Paris. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.