London audiences will finally get to see a new Jenůfa. Restrictions caused by the coronavirus pandemic halted the Claus Guth-directed production in March 2020, but the show, as they say, must go on, and indeed it will; the opera is set to open at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden on September 28th. The artistic team remains somewhat intact from its first iteration, with originals Asmik Grigorian in the lead (a role debut), and Karita Mattila as Kostelnička Buryjovka (reprising a role for which she has won much acclaim); new cast members include tenors Saimir Pirgu as Števa Buryja and Nicky Spence as Laca Klemeň; they’ll all be under the baton of conductor Henrik Nánási. That the Scottish-born Spence is making a role debut in an opera he knows well and has frequently appeared in in the past (as Števa) is a point not lost on the tenor, who was chatty and excited when we spoke recently, just between Jenůfa rehearsals and on the cusp of fresh ones for English National Opera (ENO)’s The Valkyrie, in which he’ll be making another role debut, as Siegmund, in Richard Jones’ new production of the Wagner Ring work, set to grace the stage of The Met in 2025.

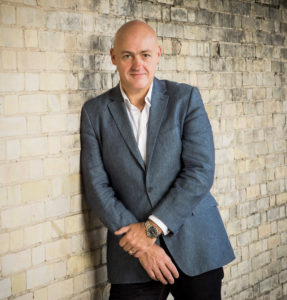

There are many tales of many artists coming from small communities and making it big in the big opera centres of London, New York, Berlin, Vienna, Paris and Moscow. Those tales tend to follow a predictable path, and indeed Spence’s tale falls into this mould: all-night buses and anxious auditions and moving from hard-scrabble Dumfries youth to London music school, and onwards, of helping relatives and settling into a house with partner and dog when success did arrive. It’s the stuff of cliché, but sometimes the cliché is simply too correct to dismiss, and besides, the brand of success Spence is now enjoying was hard-won, because it wasn’t the sort that initially came knocking. In 2004, during his final year of school at Guildhall School of Music And Drama, Spence accepted a five-record contract with Universal Classics (Decca). He went on to make his first album with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, toured with Shirley Bassey and Katherine Jenkins, and was nominated for a Classical Brit Award (as Young British Classical Performer Of The Year). During this time Universal/Decca had promoted him as “The Scottish Tenor”; Spence was in his early 20s at the time. When it came time to record his second album, Spence declined; back to Guildhall he went, for more intensive study of his craft. In 2009 Spence won a place at the National Opera Studio, and a year later joined ENO, as one of their inaugural Harewood Artists, where he did an equal mix of so-called “classic” opera (David in Die Meistersinger, The Novice in Billy Budd, Steva in Jenůfa) and contemporary: Spence created the role of Brian in Two Boys, Nico Muhly’s 2011 opera about the tragic intertwining of technology and passion based on a true story, which was subsequently staged at The Met.

Spence clearly wants to be a star, but that drive is in no way at odds with his keen musicality and theatrical instincts. An awareness of timing, texture, and technique, both vocally and physically, is evident, but Spence is smart enough not to show the gears turning – not without very good (read: theatrical) reason. Experiencing him with so-called “darker” material (which encompasses much of his core repertoire) is not so much a shock as it is a clue into an artististry still unfolding. Spence is still young, not quite 40; he’s performed on the stages of the Royal Opera, the Met, La Monnaie, Opéra national de Paris, and Glyndebourne and has worked with a range of conductors, including Sir Mark Elder, Andris Nelsons, Philippe Jordan, Donald Runnicles, Carlo Rizzi, Alejo Perez, Alain Altinoglu, Mark Wigglesworth, and composer/conductor Thomas Adès, to name a few. He returns to working with Martyn Brabbins on The Valkyrie at ENO later this year; it seemed clear from our conversation he was both daunted and thrilled by the chance to tackle Siegmund, a role that mixes dark and light, shade and nuance, in vocal writing as much as theatrical expression. So, to simply state that the tenor specializes in “darker” repertoire is to rather miss the mark, as much as for Spence as for the music; composers like Britten, Berg, Dvořák, Martinů, Zimmerman, Stravinsky, Schönberg, Wagner. Strauss, and (especially) Janáček hold an appeal for the socio-religious, spiritually chewy, stained and earthy (sometimes dirty, ugly) elements which exist as much in their scores as in the texts and characters within their works, seen and unseen. This doesn’t diminish the work of other composers like Mozart, Rossini, Berlioz, or Beethoven (whose works can be every bit as chewy – Spence has performed them also), much less the work of contemporary composers, which Spence has admitted he would like to perform more often. Taste, talent, vocation, freedom, and the infusion of personal meaning and fulfillment are rare matches in the arts world; such an integration has implications for culture and its expression in the post-pandemic landscape (if we are even there yet). In Errata: An Examined Life (Yale University Press, 1997), George Steiner ponders this equation of rare and special matches, positing its greater relevance within ever-shifting perceptions of freedom, a notion to which many culture-lovers might find their own meaning, particularly as the opera world enters (and perhaps redefines) a new normal:

Any attempt at serious thought, be it mathematical, scientific, metaphysical or formal, in the widest creative-poetic vein, is a vocation. It comes to possess one like an unbidden, often unwelcome summons. Even the teacher, the expositor, the critic who lacks creative genius but who devotes his existence to the presentment and perpetuation of the real thing, is a being infected (krank an Gott). Pure thought, the analytic compulsion, the libido sciendi which drive consciousness and reflection towards abstraction, towards aloneness and heresy, are cancers of the spirit. They grow, they may devour the tissues of normalcy in their path. But cancers are non-negotiable. This is the point.

I have no leg to stand on if I try to apologize for the social cost of, say, grand opera in a context of slums and destitute hospitals. I can never prove that Archimedes was right to sacrifice his life to a problem in the geometry of conic sections. It happens to be blindingly obvious to me that study, theological-philosophic argument, classical music, poetry, art, all that is “difficult because it is excellent’” (Spinoza, patron saint of the possessed) are the excuse for life. I am convinced that one is infinitely privileged to be even a secondary attendant, commentator, instructor, or custodian in some reach of these high places. I cannot, I must not negotiate this passion. Such negotiation, of which “political correctness” is an infantile, deeply mendacious tactic, is the treason of the cleric. It is, as in the unreason of love, a lie.

There is no aspect of untruth to any of what Spence brings to his work. His 2019 recording of Janáček’s disturbing, highly theatrical song cycle The Diary Of Who One Disappeared (Hyperion; recorded with pianist Julius Drake, mezzo Václava Housková, and clarinetist Victoria Samek, and including other Moravian folk songs) demonstrates a range of both expressivity and flexibility, balanced by a highly intelligent technical approach that in no way robs the music (or its troubling text) of its power. As he told Presto Music‘s Katherine Cooper at the album’s release, “once you’ve mastered the few sounds which don’t exist in spoken English, the Czech language is ideal for the voice as it sits forward in the resonance and feels legato in nature, with so much potential for expression in the language. As a keen exponent of his music, I feel a duty to try and commit to the Czech language like a native.” That committed approach won Spence rightful acclaim; he was the recipient of the Solo Vocal Award, Gramophone Classical Music Awards 2020 (“He sings with sensitivity and intelligence, projects the words with consistent clarity and covers this wonderful cycle’s broad emotional range movingly and convincingly,” wrote music journalist Hugo Shirley) and the BBC Music Magazine Vocal Award 2020 (Spence “combines passionate declamation with moments of exquisite delicacy,” wrote Jan Smaczny). His experience with the music of Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), whether in recital, production, livestream, or recording, has been considerable through the years, with repertoire in Káťa Kabanová and From the House of the Dead (Z mrtvého domu) alongside Jenůfa and the Songs, but there’s more yet to come; in February 2022 Spence makes his debut at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden (Berlin) as Gregor in Věc Makropulos (alongside soprano Marlis Petersen as Emilia Marty and Bo Skovhus as Jaroslav Prus) in a new production, again directed by Claus Guth, and conducted by Sir Simon Rattle. He’s also set to be Samson to Elīna Garanča’s Delilah at the Royal Opera House next spring, under the baton of Sir Antonio Pappano.

Complementing the hectic scheduling of an opera world that seems to be returning a semblance of normality (or new-post-corona normality) is Spence’s bubbly style. In his conversation with stage director Nina Brazier on her podcast, The Opera Pod, recently, he says, “I found this gift, I guess, it was like a superpower, really.” No longer The Scottish Tenor; now, perhaps, Super-Siegmund-Tenor, Spence’s past life filters into his present one: the pauses as much as the tones, the phrasing choices, the dynamic choices; the smell of hay, grass, and sea; the fumes of black cabs, the perennial buzzing of St. Martin’s Lane; everything informs Spence’s sound. Such authenticity makes his performances special, and memorable, events.

Photo: Ryan Buchanan

How are Jenůfa rehearsals going?

Hugely well – we’re heating up here onstage; my knife is sharpened, my stick is whittled, and I’m ready to go for it!

What’s it been like to step into the machinery of a production that was already largely done?

It’s been exciting. They’re such a generous group of colleagues! Although I was a newbie I felt very much welcomed into the family. I’ve never seen a video of what it was like before, so I could really put my own stamp on things. I love Claus Guth – we’re working together a lot this season; his instinct is so beautiful as a director, he really explores the grey area, which is what Janáček’s work seems to be all about.

I spoke with (tenor) Allan Clayton when he was preparing this in 2020, and again when it was cancelled; he observed that Laca has “the chippiest of chips” on his shoulder. Your characterization will be different of course, but how did singing Števa prepare you for this, or did it?

I don’t think so, really – but it did offer me the ticket into Janáček’s world and this opera, so I feel the music in my bones. Laca is such a different character, and in a way it’s much more fulfilling; the character arc is much deeper from where it starts, with, as Allan said, him carrying the chippiest of chips. Laca has so many issues in terms of abandonment and not feeling loved and not really knowing where he fits into this hierarchy – he feels like he’s at the bottom – and slowly, as he develops more of a connection with Jenůfa, during this horrendous act of slashing her face, whether it’s accidental or not, they become a lot closer. And this imperfect perfection is something I find so moving, much more moving than any Hollywood ending, the fact that everything’s gone to shit and they still decide to give it a go.

They’re both outsiders.

Absolutely, they’re misfits and they’re stuck within this mill of abuse – a generational abuse and utter emotional incapacity.

… and the social milieu, of judgement, and fitting in, or not-fitting-in, are elements sewn straight into the quality of Janáček’s music. When you first got into singing, what attracted you to it? And what keeps you fascinated now?

I think it’s his honesty, and the truth of his writing – there’s such a sense of truth to it all. I’m not sure if it’s because he had this illicit relationship, which was unconsummated, with Kamilla Stösslová, who was so very much his junior, and they were both married to other people too – but it feels as if his operas are infused, as a soundscape, with what he couldn’t have in real life. He had so much of what he would’ve loved to have happened within the writing, but the music is not quite cathartic, and what is there, well, there isn’t ever any kind of relief in that catharsis; everything is a little bit crap in the end. There’s no real goodies or baddies throughout his work; everybody is very confused, and he explores that grey area of the human condition, which I find so interesting as an actor and artist.

His writing is dramatic, and also very dense – the text together with the musical language – how do you find your way in? Through all the recitals, operas, and song cycles, has your approach to his work changed through the years?

I really enjoy the contrasts (between those forms). I try to think of something like The Diary Of One Who Disappeared as a play set to music – so it’s not just difficult rhythms but lots of other things. For instance, there’s so much folk in that work, it’s something we hear in all his music. He was a fan of Moravian folk music and you can hear it in so many things – and I’m Scottish as well, so I guess we resonate through that folk idiom. Also I love the fact that vocally (his music) does have some challenges but those challenges are so totally married to the drama. You do your work in the studio, and hopefully by the time you are onstage you can enjoy the ride.

So how did doing something like Diary inform how you do things live onstage now? Or is it the other way around – does your opera work inform your approach to song cycles? Or are they all totally blank slates for you creatively?

The songs are just like mini-operas, really, you just have less time to set out your stall in terms of your journey and the drama, but certainly something like Diary is between something of an opera and a song cycle. I very much feel it’s an operatic display, I guess, it has all of the elements in there, just the structure is slightly more like the song, but that’s the way when it comes to Janáček’s writing: it’s so through-composed that it doesn’t feel very formulaic, at all. And that’s his genius, really. I adore these darker, murkier depths of his, qualities which are quite far away from my personality. It’s fun to get down and dirty…

What’s the attraction to that, to the “down and dirty”?

I guess not being myself… and I guess, I get to explore this kind of thing without messing other people up…

… so it’s a form of escapism that’s safe?

Yes, it’s playing with those things, and when, for instance, you’re with people like Karita (Mattila) and Asmik (Grigorian), it feels very primal in a way, which is exciting as an artist.

Part of that is the notion of connecting, too.

That’s true!

You said in an exchange with The Guardian in 2016 that the most important thing at a concert was that there be “any element of human connection.” I thought of that with relation to your online activities through the pandemic, and I am curious if that idea has changed because of the pandemic experience.

For myself, as for everybody, there was a natural reordering of things. When your time is entirely consumed with learning operas, your life is one way, and I was so pleased to learn through everything that there was more than a husk of a human being behind my singing. Some people lost a lot of their their work and thus their identity through this time, but I was really thrilled to not be doing so much singing – we got a clichéd Covid-dog, and, me and my partner were just about to get married, and we had to delay that, which was annoying, but I was thrilled to be able to have some creative moments and introspection. So going forwards now I want to encourage a better work-life balance. Yes, I led masterclasses, and even though I wanted to get back onstage and go back to work, doing that was such a great way of meeting people and of having a levolor. It was important to connect with people on a universal level, but also a human one.

Your classes really reveal how much you have that human touch.

Well it’s important to be real.

Yes, especially since there’s a lot of people who talk the talk but don’t walk the walk…

There’s a lot of old bullshit in opera, a lot of the time – and in the end it comes down to personal relations. It’s about people, and about how people correspond with one another. Especially when I’m talking to young people I encourage them to get back to their roots – it’s so easy to lose that connection amidst everything.

In terms of connection, you are going to be singing Siegmund at the ENO; it’s easy to lose the idea of connection amidst the epic nature of Wagner’s writing…

… yes it is…

… so what sorts of things do you keep in mind now as you enter the world of Wagner?

Well my mind is entirely open! Although they have quite a fantastical grand feeling – they are epic tales! – The Ring operas are still very human. I know Richard Jones, our director, says these characters have super-powers, they can do things, but he also says they are real people at the end of the day, and that (notion) gives me solace. So the production will be grounded in truth. (The music) is like a long bath which Wagner draws for you, and as a singer it feels that real. I love Wagner but I mean, with Janáček, these dramatic changes (in the music) happen quite quickly, while in Wagner, they don’t turn quickly – they turn like a truck! The music is like a truck turning a corner – and that’s really lovely musically, because as a singer you have more time to change gears, and vocally it feels like a nice thing for me, so… yes, I’m really excited for this production.

What new things are you learning about your voice through the experience of singing the music of Janáček and Wagner simultaneously then?

I’m always learning new things, gosh, every bloody day! I wish singing was a bit easier! You are always opening new fields, understanding the more you know and don’t know about signing, which is really humbling. And with this sort of singing, you are waking up with a new instrument every day – and with Wagner, because it’s quite low, I’ve been lucky to have that vocal release. It’s been nothing like the Janáček (to sing) – (Janáček’s vocal writing) is quite high, it’s where I am used to sitting, really. The writing is quite tightly wound and it sits high, so the character sits quite easily. But (with Wagner) I am finding the extra release in the lower range. I normally make quite a bit of noise… and I am aware Wagner normally demands a lot of noise, so yes, I am looking forward to making some noise in The Valkyrie.

That’s a noise you modulate through your recordings – you have a few coming out soon, yes?

Yes, I’m singing Vaughan Williams’ On Wenlock Edge with (pianist) Julius (Drake) – that’s out in February; there’s also my first Schubert, Die schöne Müllerin, with (pianist) Christopher Glynn, releasing the month after … and, La Clemenza di Tito with the orchestra of the Opéra de Rouen Normandie. We recorded that in lockdown. I did quite a lot of Mozart in my early career but I’ve not done any recently. It was fun to delve back into that music.

Luca Pisaroni once told me he finds Mozart is like a massage for the voice.

Yes it is, and there’s also nowhere to hide when you do it. You can’t make it up – it’s like a singing lesson. Whatever you think you can sing, and however you think you can do it, you pick up some Mozart or Bach and you go, “Oh hell, I need to learn how to do this all over again!”

So it’s a good balance to what you’re doing now?

It’s a perfect balance.