Pelléas et Mélisande is an opera that inspires automatic if not always well-founded ideas: it’s (seemingly) impenetrable; it’s the French Tristan und Isolde; it’s romantic; it’s intense; it’s ultimately very tragic. It is also, in the words of conductor Hannu Lintu, something people may find “baffling.”

Yet Lintu, who is currently leading a new production of the opera with Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, has found a unique clarity in Debussy’s 1902 opera, itself based on Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1893 symbolist play of the same name about a tragic love triangle of two half-brothers who love the same woman. Dutch director Jetske Mijnssen’s new staging premiered earlier this month as part of the annual Münchner Opernfestspiele, a co-production with The Dallas Opera running through 22 July featuring Ben Bliss and Sabine Devieilhe as the doomed titular lovers, along with Christian Gerhaher as the jealous Golaud, Sophie Koch as Geneviève, and Franz-Josef Selig as Arkel. Lintu, who is also Chief Conductor of Finnish National Opera, emphasizes the work’s episodic structure and uses its orchestral interludes not merely as time-filling transitions but as both commentary and complementary characters on and within the unfolding narrative. This musical approach serves to heighten the dramatic interplay between characters as well as underline the extreme tension of their world – its mystery, mysticism, and narrative momentum. Set and costume designer Ben Baur has created a world that channels both the time of the opera’s premiere (the early 20th century) while adding abstract elements and making substantial use of water, which becomes a visual motive. The decidedly structured approach Lintu takes to the score is intriguingly complemented and contrasted by such textured visual cues, highlighting both the form and the formlessness that awkwardly co-exist and fight for dominance via the interwoven relationships within the opera.

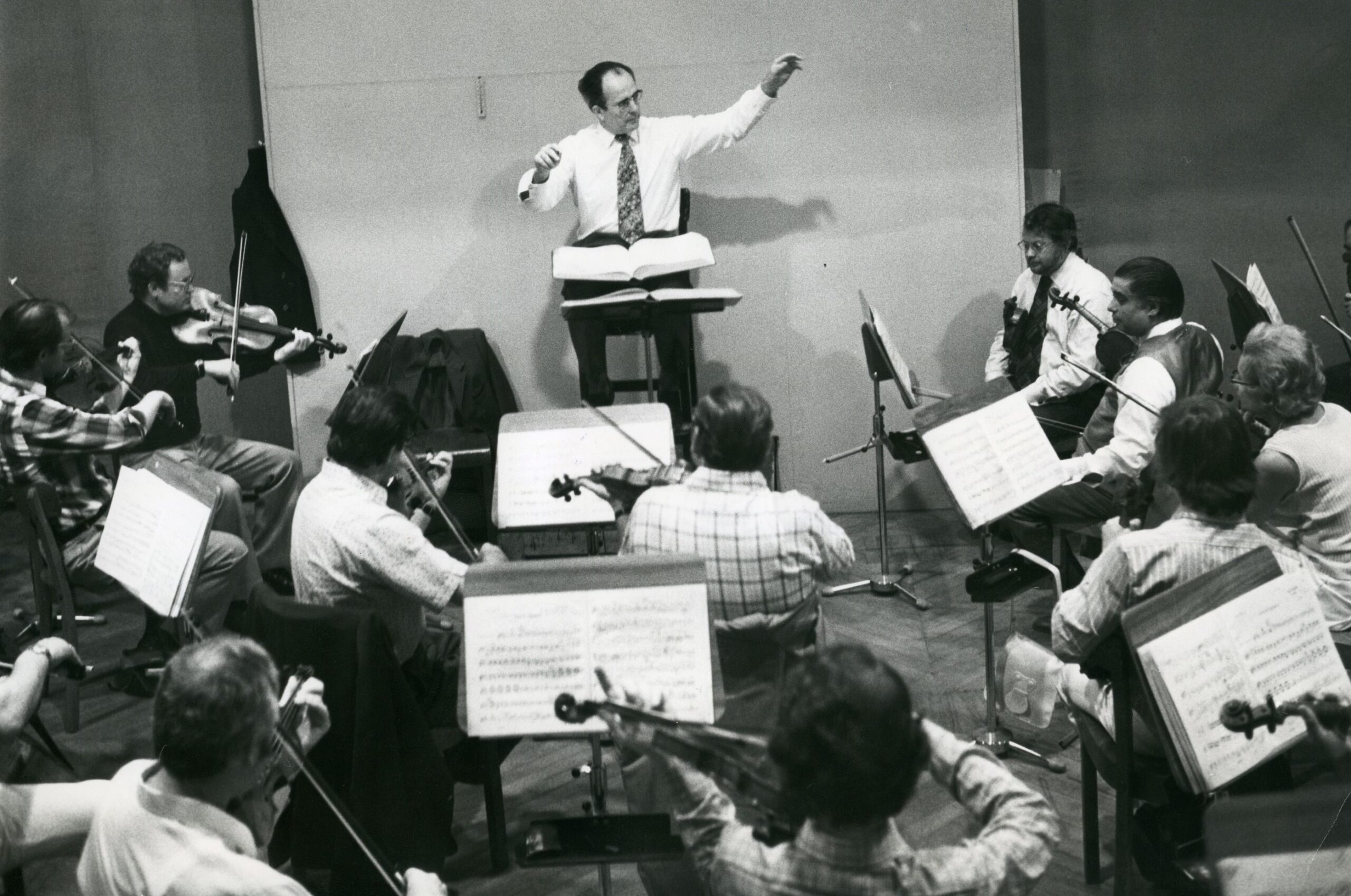

Along with his duties at Finnish National Opera, Lintu is also Music Director of Orquestra Gulbenkian in Portugal, and will become artistic partner of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra in Finland in autumn 2025. He has lead a number of celebrated orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal and Orchestre National de Radio France, to name a few. Lintu’s varied repertoire features an intriguing mix of old and new, with a distinct focus on the latter; the works of contemporary or near-contemporary composers (Magnus Lindberg, Thomas Larcher, Sebastian Fagerlund, Kaija Saariaho) feature prominently along with an assortment of 20th century works by Lutoslawski, Berio, Zimmerman, and Messiaen, with recordings done for Ondine, BIS, Naxos, Avie and Hyperion. A 2012 recording of George Enescu’s Second Symphony (Ondine) with Lintu leading the Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra was shortlisted for a Gramophone Award, one of many nominations the conductor has received from the prestigious music magazine, and one of many outlets who have praised and recognized his wide-ranging work; Lintu is multiple GRAMMY nominee who is also the recipient of two International Classical Music Awards.

In his native Finland, Lintu has lead a range of operatic works including Wozzeck, Ariadne auf Naxos, Don Giovanni, Dialogues des Carmelites, Turandot, Salome, and Billy Budd. Earlier this year he completed the house’s massive Wagner Ring Cycle with Götterdämmerung, having already lead performances of Die Walküre and Siegfried from 2022. Music writer Anna Aalto noted in June that “(u)nder his direction, the orchestra’s sound is rich and velvety, and the details of the music are thoughtful and intense. The brass section stands out as mesmerizing and well-balanced.” (Seen & Heard International, June 6, 2024) This attention to balance is just as noticeable in his Pelléas in Munich. Lintu and I spoke about achieving that balance, along with his history with the opera, the role of language, and his ideas on the notion of “colour”, a word important to the music of Debussy, and not always easily achieved. Our conversation took place two days after the production’s opening, with the conductor offering detailed musical reflections, highlighting the work’s inherent connections to its contemporaries as well as its inherent mystery and beauty.

Ben Bliss as Pelléas and Sabine Devieilhe as Mélisande in Bayerische Staatsoper’s new production of Debussy’s opera. Photo: Wilfried Hoesl

When did you first encounter Pelléas? And how have your perceptions changed since that time?

The history is long – I remember when I was still in high school and I was playing piano and cello. I always went to a local music library, which was huge, and I remember borrowing the score of Pelléas and and trying to read it and realizing that I couldn’t understand a single measure of it. I was probably 16 or 17 and I had already been playing Debussy’s preludes and things like that, but I had the feeling that (the opera) was some kind of thick forest which I could not penetrate or even step into. But I was listening to it a lot with the score when I was young.

Then I started to study conducting – I became very symphony-focused – though I saw a couple of productions at various points and then bought the score because I thought, ah, that it’s one of those pieces of the 20th century that I really need to know! My approach then wasn’t for performance but purely for analysis. I bought the play also, the Finnish translation, and read it a couple of times, and I knew a bit of the philosophy in its background, although I always found, as a whole, it was difficult to digest as a musician; it takes time before this work gets into your system. I could see the details but I couldn’t put them together, a problem throughout much of Debussy’s music: it’s made up of so many details and so many layers, hidden meanings without an actual horizontal line – well it is horizontal, but not in the melodic way, it’s mostly it’s vertical, with many fascinating things going on with the harmonies and the middle voices. So I was lost in the forest, metaphorically, in a different way – but now I could actually penetrate that forest.

In preparing for this production I started to work on two different levels: studying the score as if it were a symphonic poem of some kind, and reading the text. I’m not a French speaker and I knew that I would be working with these fantastic singers who, all except one, speak French – and I have done some French operas, like Carmen, Dialogues des Carmelites, but Pelléas is a very different approach to the French language. When I came to Munich and met the soloists for the first time I said, “Look, you have all done this” – except Christian Gerhaher, who had sung Pelléas before, not Golaud – “but you have done this and I have not.” It was actually a fascinating situation. I said, “I am now approaching you, actually not with a solution, but with questions.” This was my attitude during the whole rehearsal process: I wanted to learn from them.

When the orchestra came in I tried to combine the German orchestra sound and my own orchestra sound into something which I think might be a little bit French. It’s been a very complex and joyful process at the same time. It’s fascinating to think about all the ways music goes into musicians’ brains, and then of course how it comes out, because it’s not only just getting it into your system, but it’s also technical: how does this music enter into my technique? And how am I able to transmit my ideas to the musicians?

I want to pick up on one of those ideas; you said in a Staatsoper video interview that Debussy should be “in shape”– I could hear that structure at the premiere. Did this arise through that study or was it something that came with rehearsals and being around singers?

Well, at some point the themes became more familiar, and they clarified especially when I started to see what was about to happen on stage – when I saw the movement. For me movement is really important; I play with it. I need to see people moving when I conduct opera, because that gives me a goal. Each scene in Pelléas has its own musical shape; each one of them is a musical piece as such, which could be performed separately, almost sometimes in some kind of a form, not necessarily a classical form, but maybe a form which comes from, even from earlier times – Renaissance or Baroque. Each scene has its own arc. The only piece that comes to my mind here is Wozzeck, which is built in the same way; each scene has its own musical form. But for Debussy it was more, I think, subconscious in the way he created Pelléas.

At some point during the rehearsals I tried to play each piece, each scene, as if it were the only one, standing on its own feet. And then later when the orchestra came along, I tried to connect these forms. How the story develops is actually very strange because so little happens in the beginning. When the first act ends, I always have this feeling like, “Where is this going?”

… which is very symbolist…

Yes! And these symbols say a lot about the time in which the opera was written, in 1902. I remember when I read the play for the first time, those symbols were a little bit more touching and I have a feeling that Debussy lost part of the symbolist nature of the play because he was so involved with the vocal writing and the orchestration – I might be wrong! The form is there, then it develops, eventually into disaster, but then it doesn’t end – there’s one more act, which is almost half an hour, like a kind of epilogue. The question arises: why did Debussy take it there? Maybe he wanted to create another world. The structure of that final section is entirely different than the others. The whole opera is episodic, and I wanted to show that this epilogue is commenting on what has happened before.

Sabine Devieilhe as Mélisande in Bayerische Staatsoper’s new production of Debussy’s opera. Photo: Wilfried Hoesl

I suspect the epilogue is also a commentary on the nature of inherited trauma…

You could be right.

… the musical language has a sense of doom. Regarding that language, I wonder how much of your other work, particularly that of Messiaen, Berio, Enescu, and of course Kaija Saariaho, was in your head when you were going through the score.

It wasn’t consciously doing that, but now that you say it, there’s lots of Kaija’s music, especially in that fifth act of Pelléas. As to Messiaen, I just conducted some early works of his, and they are very Debussy-like in the language – so I think that’s where his harmonies grew from, although it’s organized as an instrument, of course, and turns the musical language to another direction.

You can approach Pelléas from two different sides: from the past, which would include Wagner and probably some French composers before Debussy; and then of course, what came afterwards. I think Debussy is one of those composers we all know was incredibly influential in terms of what’s happened in the 20th century – him, Stravinsky, Webern, and all these great masters from the beginning of the 20th century. Their works are still modern. We probably need to live a couple of hundred years more before we really understand their music. I was thinking about this other night – we pretend that we do (understand), but especially with regards to Debussy, except for La Mer, people are a bit baffled. “What is happening? I don’t get it. I’m getting a little bit intimidated” – whereas the musicians are like, “Oh, this is so beautiful!” Debussy’s music hasn’t entirely reached the ordinary public, but it is going to – it is still travelling towards us.

Or us toward it…

Yes.

Do you think that the journey for appreciating Debussy might be helped along by programming more contemporary, or at least complementary composers more often?

I have always believed in showing the connections, whether it’s the connection between Beethoven, Wagner, or Mahler, or Mahler and Berg. I understand that the people who come to concerts may not have time, knowledge, or interest in educating themselves in this way. But I think we, who plan the programs and do the programming, could take a little more responsibility and gradually show them that the history of music is continuous, and that’s how the so-called canon is built. And those composers who are important, they are important because they influenced others, not because some musicologists or musicians have decided that they are or must be the greatest. They would have been great anyway, because they affected so many other composers. I think of Kaija and I know that some of her ideas, yes, came from Debussy and some of them came from Messiaen, and some came from others.

Photo: Marco Borggreve

So what kinds of things do you carry back, then, from this experience? You’re not finished the run yet, but what ideas or approaches might you carry back to the Finnish National Opera?

I don’t know yet, but certainly, whenever you do a big piece like this, which is, again, if we are talking about the 20th century, if we’re talking about Salome, Elektra, Wozzeck, these pieces which every conductor wants to do, you think of the structure. If something has changed, I’m not sure what it is yet. I’m almost sure that if I have changed, I will notice it after I have started to do something else. When the run here ends, I will be going on to Cleveland, Music Academy in the West, Tanglewood and Taipei also, doing the music of Sibelius, Walton, Mahler, Bruckner, and Saariaho… so when I get into the various pieces I’m set to do in those places, it’s possible that I will do them differently because of this experience – but I don’t know it yet, because now I’m still living Pelléas here.

“Colour” is a word used not only applied to the music of Debussy, but to that of many composers whose works you’ve done. Have your ideas on colour changed through the years?

We tend to speak of colours in music and very often we don’t actually have any idea what we are talking about. You read the critics: “Oh, there’s those wonderful colours” – but sometimes it’s just words. There are composers like Sibelius, who was incredibly synesthetic in his thinking, and he heard every key in its own colour, but then there is no direct connection from this into the score itself, how we experience it and how we play it, so I would say that colour is technique. It’s the composer’s technique to orchestrate, and then the musicians’ technical abilities to do exactly what the composer wanted to do. Debussy wrote a lot of instructions, as did Mahler and Bartok. You should read those instructions carefully. They knew words, and whenever there’s a word in the score, they are very important. But mainly colour is a very simple thing: play at the tip of the bow, or more pressure, or short, long, achieving a balance that reveals and makes those colours.

If you look at the orchestration of Pelléas, you very soon noticed that use of brass is very subtle; they very seldom play. A tuba plays probably four or five notes, and there are some beautiful trumpet melodies also, as well as various motives – I almost think that that’s something he learned from Wagner’s scores. It was actually something we worked on, the brass balance. So… yes, colour is technique, it’s orchestration, and then trying to do what the score says.

Christian Gerhaher as Golaud and Sophie Koch as Geneviève in Bayerische Staatsoper’s new production of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Photo: Wilfried Hoesl

How do you think this plays into the vocal writing? You said in another interview that it’s very in the middle – have your ideas changed throughout rehearsals?

They have changed, but only within the last eight or nine days. Originally I thought – and I still think – that they are essentially instrumental parts with words. They are in the texture of the overall sound. They have their own character, and sometimes they are peculiar. It also took me some time before I realized that the French language needs to have certain rhythms, even more than other languages. Every language has its own character, but now when I really know the words (to Pelléas) better I realize that if I try to speak them, then the character comes through the spoken rhythm and its related spoken tempo.

Also if you listen Debussy for three-and-a-half hours you have to have some variation in the sound, it can’t always be just one sound, “French” or whatever; you really do need to be earthbound for this opera. You need to find the structure and maintain the intensity and momentum, and keep some sense of direction pushing it through. You listen to recordings of Pelléas and that all of that comes through, even if the recordings are very different from each other; I can’t tell you which one are the best ones, maybe I admire the ones which are more orchestra-focused – but yes, I always thought that I have to treat those vocal parts as instrumental parts, that I have to make the balance where the words are, that they need to come through somehow. And it’s not always possible. With every opera, you have to make some compromises in balance. And having a Dutch stage director, a Finnish conductor, a German orchestra, a French singer, a German singer – it is inevitable that we all have our own national characteristics when it comes to the music, but sometimes it yields fascinating results.

Top photo: Veikko Kähkönen

On Stravinsky’s Soldier: “We Have To Safeguard The Things That Matter In Life”

By Catherine Kustanczy

On July 15, 2018

In Canada, classical, Europe, festival, interviews, music

This year’s edition of the Toronto Summer Music Festival has a distinctly Russian flavour.

The festival (initially founded as the the Silver Creek Music Foundation in 2004) opened this past week with a concert by the celebrated Escher Quartet, who performed a program of works which included string quartets by Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky, respectively. The following night, members of the quartet joined pianist Lukas Geniušas and TSMF Artistic Director (and Toronto Symphony Orchestra Concertmaster) Jonathan Crow for “Mother Russia“, a concert featuring the music of Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. Moscow-born pianist Geniušas showed off his considerable technical abilities and a very expressive approach in the (piano-only) first half, his rendering of Rachmaninoff’s Preludes (Op. 32, No. 9-13) a gently modulated collection of lights and colours. Likewise, his work with members of the Escher Quartet, joined by Crow, showed off a considerable lyricism; altogether, the troupe provided a round, even sexy, approach to the jagged angularity of Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 57.

Audiences can look forward to further concerts with Russian works, including a presentation of Stravinsky’s “L’Histoire du Soldat” on July 19th. Composed in 1918 when Stravinsky was facing tough times (including the recent death of his brother and serious financial shortfalls), the piece (“Histoire du soldat lue, jouée et dansée en deux parties” or (Story of the soldier to read, act and dance in two parts”, in full) was written with Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, a French-Swiss writer who he’d met as a fellow ex-pat in Paris just before the First World War. The work retells the Faust myth using a litany of musical styles and folkoric elements inspired largely by the work of Russian writer Alexander Afanasyev, one of the most famous Russian folkorists of the 19th century, and a big fan of the Grimm brothers’ work as well. Originally intended as a touring work, “L’Histoire du Soldat” has been produced in a variety of styles and iterations, though most commonly with one narrator doing all the roles, with musical accompaniment. Isabel von Karajan (daughter of conductor Herbert von Karajan) performed the work with members of the Berlin Philharmonic to great acclaim in Salzburg in 2011, and then in Berlin in 2012; it’s also been presented with pantomime elements in 2013, recorded with Jean Cocteau and Peter Ustinov in 1962, and, rather poignantly, by Carole Bouquet, Gerard Depardieu, and (deceased) son Guillaume, in the mid 1990s in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées. Stravinsky may have written “Soldat” out of basic financial necessity, but the work has proven to be a wonderfully enduring piece of music theatre, one that showcases his changeability and elasticity as a octopus-like composer with a multitude of legs moving easily between sometimes wildly varying eras, styles, sounds, and artistic movements.

Canadian music artist Alaina Viau is bringing a new production of the work to the Toronto Summer Music Festival this coming week, featuring dynamic Canadian talent including theatre artist Derek Boyes and choreographer Jennifer Nichols. In her day job, Viau is Assistant Production Manager at the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, but she’s also the founder and Artistic Director of sparky independent company Loose Tea Music Theatre, which specializes in presenting creatively-staged opera in and around the Toronto area. Viau has worked regularly with a variety of artists in various disciplines (including dance music, cinema, and visual art) to present re-imagined productions of opera chestnuts like Bizet’s Carmen and Gounod’s Faust.

The latter is especially relevant to Viau’s work with “L’histoire du Soldat”, but so is her interest in and commitment to social justice issues, especially as they pertain to contemporary presentation within the operatic form. I recently spoke with Viau about why this piece is so timely (and perhaps timeless), her decision in casting the lead role with a woman, and how her work as director of production for the TSMF presentation of Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” contrasts and complements that with Stravinsky.

Alaina Viau (Photo courtesy Toronto Summer Music Festival)

What’s it like to stage “Soldat” for the first time?

Exciting! I’ve known this piece for a long time and I’m what you’d call a Stravinsky nut! I have a lot of literature on Stravinsky and bought a special edition of Rite of Spring when it came out years ago; I have new book on him, and all his letters and things like that.

How did you come to direct this?

I’d only ever heard it in the way most people hear it, with one person narrating all the roles, and then the ensemble around them. Jonathan Crow and I started talking about this project two years ago — I work for the TSO as well, and the TSO Chamber Soloists (of which Crow is a member) were doing a series of performances of this piece; it was done at Roy Thomson Hall and the Art Gallery of Ontario and at the Hearn (Generating Station), and at that time, it was just with Derek Boyes and the ensemble. It was then that Jonathan and I got talking about how we’ve never seen it fully staged, and what a shame that was, because it was originally written for a touring performance with actors and a set and such, so we said, “Hey we need to see this!”

So TSMF audiences will see a full type of production?

Yes. We have Derek, who is doing the roles of the narrator and the devil — because he does such a great job with the devil! – and we have a dancer/choreographer, Jennifer Nichols. We also decided to cast the role of the soldier as a woman — traditionally it’s a man, but… it’s an all-male show, and Jonathan and I were like, “That’s kind of shitty!” We don’t change the relationships with the fiancee or the princess — it’s any relationship, really. We didn’t feel we needed to harp on that fact; it’s a relationship that exists. I wish I didn’t even have to say that, really. The idea came through conversations on gender parity. There’s a lot of men in the show, and a lot of men in the ensemble, and we were like, “That’s a lot of men on stage! It isn’t fair; I think we can fix this.”

How much were you influenced by what you’d seen and experienced as a Stravinsky fan?

I don’t believe I’ve taken any influences in doing this. I’m sure there are some references to some of the research I’ve done, but what I’ve seen (of Soldat) I haven’t really liked. So that is a thing: I have decided not to do some things. That is an influence of sorts! I knew what I didn’t want. That is sometimes just as strong, if not stronger, than seeing things I do like, so I was able to really think, “Well I want to make this fun, engaging, with great music, and a great story” — it’s a warning story.

… although it can be presented as drily didactic as well. I would imagine as a theatre practitioner you have to be careful not to wave a finger at your audience. “Fun” and “engaging” are the words I’d use to describe what Loose Tea does.

Well it is my style, and my question is always, “Why tell this story now? Why does it matter right now?”

So why “Soldat” now?

It’s a story of being too greedy, of consuming too much, of not being appreciative of what you have. That’s something I think we can always relate back to stuff in the US and what could potentially happen in Canada: we need to be aware of what we have, and not be greedy. We have to safeguard the things that matter in life. What the soldier comes to learn is, in fact, the things that matter are things that money can’t necessarily buy, that there is greater value in having some sort of meaning in life. I think that’s a tale that is always worth telling.

It’s timeless and timely and really elastic, not solely in themes but in presentation possibilities.

Yes, and what I really like is that it’s not a happy ending — he gets the princess and then screws it up again. It’s that reminder that you have to be constantly working on that aspect of yourself.

It’s a wry comment on the nature of humanity also, the nature of which seems very Russian in nature.

That too. The question is, how do you tell this story to a Canadian audience, who may not have that understanding of Russian folklore? That folklore is quite brutal sometimes.

How does your work on “Quartet for the End of Time” complement what you’re doing with “Soldat”?

I get excited about it, really. What I’m particularly enjoying is that I did a Masters degree in music, and it’s really nice to geek out and go back to the score, do my research, do my score study — it really helps me come to important realizations.

For the Messiaen, all I’ve been doing for months is consuming a lot of research, which I love doing, and really trying to think about how Messiaen saw the piece. He had synesthesia, and we wanted to explore not just what he saw but what role this plays overall: why do we care about “Quartet for the End of Time”? Why do we care about the visual aspect of it? And how can we make it make sense to us? Because he was very religious, and in the context of the Toronto Summer Music Festival… religion is not a really strong (theme), it’s not the strongest point to bring out in this piece.

But it’s unmissable in the music.

Yes. Although he wrote it with religion in mind, something that really inspired him, and what I think may inspire many people, is a commonality of hope of this piece.

That sense of hope contrasts with the ending of “Soldat”quite strongly.

It is what got him through his internment in the camp; he couldn’t escape physically, and the more difficult things became physically, the more he escaped into his brain. You hear it in this Quartet — because he did have a strong sense of hope and of things working out, even in an internment camp.

Vision over visibility.

Yes, it’s a good fit with the festival.