Photo: CF Wesenberg

The last time Vasily Petrenko and I spoke was in a windowless room full of whirling fans. There’s still a feeling of summer in September in Bucharest, and this year’s heat was particularly intense; I was worried conditions in the Sala Palatului conference room would prove a bit too warm for a conversation about the music of Enescu, Bartók, and Torvund.

The busy conductor, a native of Saint Petersburg, was in town for two concerts as part of the hectic Enescu Festival with his Oslo Philharmonic, of which he is Chief Conductor. (My report on the festival featuring said interview is publishing in the upcoming winter edition of Opera Canada magazine.) Despite the heat, Petrenko was his lovely, chatty self, full of insights, observations, and charming stories. His concerts, with soloists Leif Ove Andsnes and Johannes Moser, respectively, were met with outpourings of loud cheers and happy shrieks, to which he jovially responded with a broad smile, playfully encouraging gestures (one hand, then another, on ears with matching eyebrow waggles and forward-leans), and energetically performed encores.

At the Enescu Festival, September 2019. Photo: Andrei Gindac

That joviality was revealed again in a more recent conversation, this time over the telephone, with a bit of tags-and-snags at the start. “It’s a big building!” Petrenko exclaimed about the Metropolitan Opera, where he’s making his company debut leading a revival of Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame (also known as The Queen of Spades), featuring Yusif Ayvazov as the tormented Hermann and Lise Davidsen (also making her Met debut) as Lisa, in a 1995 production by Elijah Moshinsky. Based on the Pushkin novel, the work is set in Saint Petersburg and is a haunting love-gone-awry tale with strong elements of the supernatural, the sadistic, and the spiritual. The production opens tonight (November 29th) and will be broadcast live on Met Opera Radio on SiriusXM as well as streamed at the Met Opera’s website.

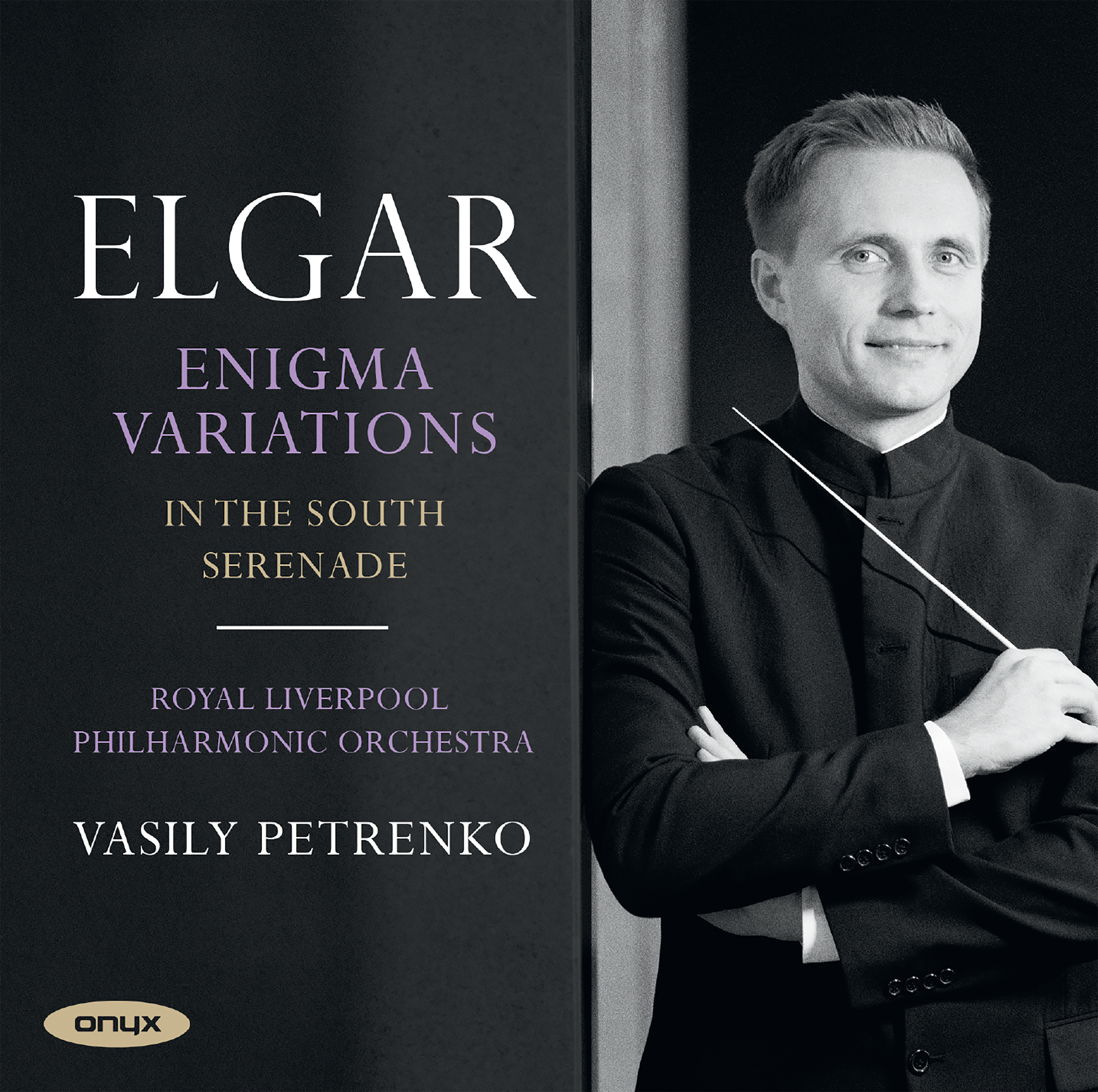

Petrenko is making his Metropolitan Opera debut amidst a raft of conducting duties. As well as being Chief Conductor with the Oslo Philharmonic, he is also Chief Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and European Union Youth Orchestras, and Principal Guest Conductor, State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia (“Evgeny Svetlanov”). As of 2021, he becomes Music Director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and has big plans for presenting the work of Mahler. His latest albums including a beautiful, sensitive recording of Beethoven’s First and Second Piano Concertos with pianist Boris Giltburg and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Naxos), and another (again with the RLPO) featuring the music of Kabalevsky, Khachaturian, Shchedrin, Mussorgsky, and Rachmaninoff (Onyx).

These are part of a vast discography comprised of Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Strauss, Liszt, Szymanowski, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, and more; when I interviewed Petrenko this past spring following the announcement of his Royal Philharmonic appointment, I swooned over the awesome beauty of his Elgar interpretation, writing the recordings “brim a lively, warm energy, a keen forward momentum, effervescent textures and poetic nuance, underlining the joy, drama and humanity so central to Elgar’s canon.” That humanity is so palpable experiencing Petrenko live. It’s hard to overstate the warmth he brings to even the most brutal of scores, an innate beauty which allows the listener to experience deeper, more vivid shades and textures. Much of that comes down to a detailed approach, something Petrenko emphasized in this, our latest conversation, with him happily chatting for thirty minutes between rehearsal sessions at the Met.

Petrenko’s current experience in the Big Apple has not been without surprises. The Queen of Spades, meant to have been his New York debut, was temporarily placed to the side when Petrenko stepped in at the very last moment earlier this month to replace Mariss Jansons on the podium on what turned out to be the final stop on the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) tour. How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practise, timing, and as it turns out, knowing Shostakovich Symphony No. 10 very, very well. Critics were effusive in their praise of the concert, with Musical America hailing Petrenko’s “palpable sense of musical storytelling” and noting his “hard-driven approach… added a welcome edge of hysteria to the suspiciously sugary main theme. A willingness throughout his reading to explore ambiguities often hiding in plain sight gave the rush to the finish a quality that was both exhilarating and appropriately double-faced.” The praise, however, doesn’t feed in to pressure, because as Petrenko explains, that feeling comes from a different and far more personal place. I’ll let him explain.

Mariss Jansons. Photo: Martin Walz (via Berliner Philharmoniker)

Update: Maestro Mariss Jansons passed away on November 30th, 2019, one day after this feature was posted. On his Facebook page, Petrenko wrote about his experience with the famed Latvian conductor:

I have always felt like I am walking a little in some of the footsteps of Mariss Jansons: most tangibly in the personal and artistic footprints he left with his long and illustrious tenure at the Oslo-Filharmonien, where it is such an honour to be his successor, but he has been a defining and deeply beloved presence from my earliest days, attending his rehearsals and masterclasses in St Petersburg, and through his legacy of concerts, recordings, lessons and advice, that have always been a touchstone for me. Thank you, dear Maestro, for all you’ve given to us, for your smile, generosity and warmth, and for simply bringing all of your heart into our musical world. It was a joy to be able to make music last week with your wonderful colleagues in the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, although those circumstances are now framed with such sadness. You will always be alive in our memories, in our souls and in our performances.

Larissa Diadkova as the Countess in The Queen of Spades. Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

How are rehearsals for The Queen Of Spades going?

We just finished one rehearsal and ready for another in forty-five minutes. It’s a lot of work as always and especially for the last ten days for so before the first night, so we’re all working hard at the moment.

And you were at Carnegie Hall too!

(Laughs) I was there yesterday just to listen…

How did it happen that you stepped in for Mariss Jansons? You studied under him at one point, yes?

I grew up attending his rehearsals and concerts with the Leningrad Philharmonic, and later in the Conservatory I had Master Classes with him. I wouldn’t say we’re friends – there’s a big age gap between us and he’s from a different generation – but we spoke with each other several times and in some ways I’m following his path in Oslo, with the Philharmonic there.

What happened here is that after rehearsals here at the Met one day I came home, and had a phone call about midnight actually, asking if I could be available for the next day’s concert at Carnegie Hall. I said it would be my greatest honour to save the concert and to help with Mariss if he will not be able to conduct for the next day. They didn’t change the program, and luckily I know all the pieces very well – I had performed them many, many times – so it was a case of, let’s see what tomorrow brings and in the morning we’ll have a decision. So the next day I went to the Pique Dame rehearsals at the Met in the morning, and during that time I was brought the scores for the BRSO concert, and after that there was a forty-five-minute rehearsal with the (BRSO) in the evening, and then the concert. They are a great band, an incredible orchestra with a lot of incredible soloists – one of the top bands in the world – and, to their credit, they are also very flexible. I haven’t heard how Mariss interprets Shostakovich 10 with them so I guess I was doing it slightly different than he had done it on tour, but for orchestra to be able to follow with different interpretation almost without any rehearsal… huge kudos to them. The chemistry happened very quickly between me and the orchestra. I think part of it is because there was no other option! It was a great pleasure to be stage and it was a good concert, and it was a good party after the concert! They’d had the last concert on their autumn tour and were departing back home.

At Carnegie Hall, November 2019. Photo: Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

So you got a direct taste of New York audiences through this.

It was a very warm audience, with a lot of cheering and applause. I visited Geffen Hall for a concert with the New York Philharmonic, in which Esa Pekka (Salonen) was conducting the other week, and I’ve seen things here in the Met too, and you always sense a lot of excitement with audiences and a lot of openness and cheering, which is always very nice for the artists.

How much of that creates pressure creatively?

I think talking about pressure… to me honestly, the pressure is always only about myself, it’s only about doing better than the last performance. It’s a sort of perfectionist pressure which I always have in my veins, and which I always feel in that sense.

So how does that translate into a house like the Met?

It’s one of the largest opera houses in the world, and we are trying to do our best, listening to several performances of operas over the past few weeks. I’m also figuring out how to do things in the pit while balancing onstage action to allow the soloists and music to sound natural in such a big place.

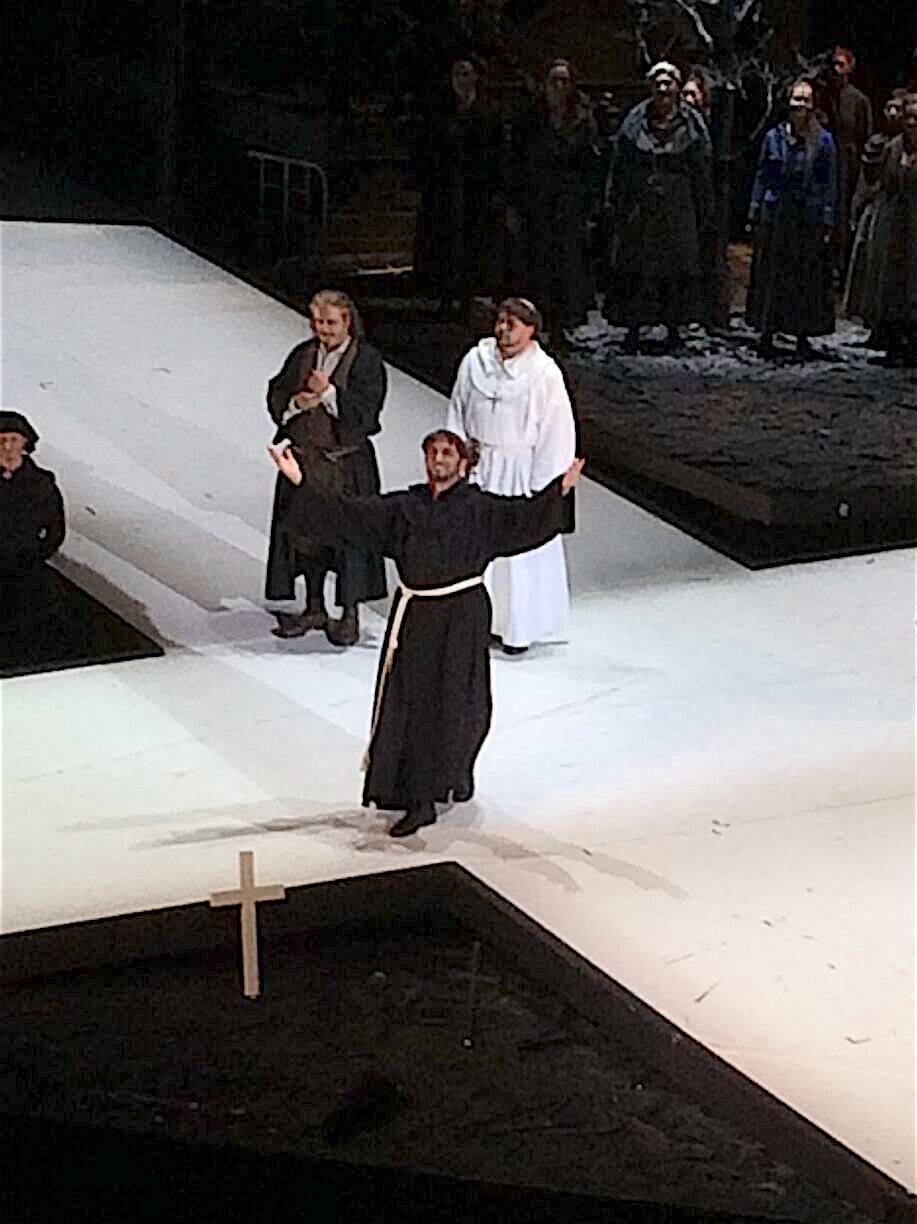

A scene from Act II of The Queen of Spades. Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

You have an interesting personal history with this opera.

I was in it as a boy in the 1980s, as a member of the famous production at the Kirov Opera, because I studied at this special boys school, and several students from there were usually in this production as a choir, so I was one of the boys singing. There are a lot of memories. Later I did a production at the Maly, one of my first revivals was actually was at the Maly Opera Theatre, now the Mikhailovsky in Saint Petersburg, when I was working there; then I did a revival in Hamburg, so (Pique Dame) has been with me throughout my life. I think it’s one of the greatest operas ever written. It has so much meaning and passion, so much philosophical subtext. If you read the Pushkin novel, that’s one of the most incredibly written, equilibristic pieces of literature; it’s compact, it has all these E.T.A Hoffman-meets-Mephistopheles elements in it, and the history and the language, as well as the symbolic things, are absolutely incredible. Very few pieces of Russian literature within the short novel genre surpass this one by Pushkin.

How do you express all that in a production that is so well-known?

There’s always a place for some mystery and symbolism – the Countess breaking through the floor in the scene with Hermann, that’s a moment! Is it his vision? Is it real? When she appears at the end with the gambling scene, is it his vision? What happened with Lisa? There’s plenty of questions you have to answer for yourself. What is the main intention of Hermann? Is it cards alone or related to self-establishment? He’s a German person who lives in Russia in a very different society and deliberately decided to live there, even though it’s not the most happy life in the beginning, and where it leads him… there’s plenty of angles in this opera, and working with soloists and talking about all of this, with sections, and trying to find the right colors in the orchestration and the right balance in the orchestra itself, it’s one of the processes we’re in now.

Photo: CF Wesenberg

How has your understanding changed, especially in light of your symphonic work?

Quite often people ask me what’s different between orchestral and opera conducting, and I think a while ago I found a good image, which is quite true: when you conduct an orchestra it’s driving a car; when you conduct opera, it’s driving a truck or big van. On one hand, driving a car is more manoeuvrable, also you all enjoy company of yourself and you’re not caring so much about certain aspects – you can do what you want, and quickly. When you drive a truck you should be aware of all the movements – the time and response of this big vehicle are paramount – but on the other hand, you can bring many more goods to the people.

But you have to be more careful about delivering them.

It’s different, because opera has many more people involved, rather than in symphonic concerts. However, the principles are the same. Even in very loud moments, you have to be aware of the transparency of what the composer has written, and you must pay very big attention to all the details the composer put in the score, either in a symphony or opera, and then there is also that something which is beyond the notes: what is most important? What is this music written for? What are the emotions? The philosophic concepts? What is the impact on the audience? It’s not just quavers and semiquavers and quarter notes, it’s moving beyond that. We’re going this direction in both opera and symphony. And of course, when you work in opera, you aim to be careful of the balance between orchestra and soloists and choir. This production has such an incredible cast, each one is outstanding. I’m very lucky to have all of them onstage, and a great chorus too – they’re doing a very good job. I think we have one live broadcast too!

Lise Davidsen as Lisa and Yusif Eyvazov as Hermann in The Queen of Spades. Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

So perhaps just a bit of pressure for that live broadcast… ?

I don’t feel pressure about that, really. Again, I’m more thinking about how musically it will all go together, and how I can deliver, how things can gel together – all the soloists, all the orchestra, and all the technicians. There’s a number of scenic effects, some moments when you have to wait or slow down the pace just to achieve the synchronicity between staging and music. It’s a classy production, I’d say. Saint Petersburg is one of the classiest cities in the world for its architecture, especially the Winter Palace – there’s no comparison to it around the world, it’s a unique creation of Peter The Great – so it’s the same feeling in a classy production. There are plenty of details but none of them is not necessary, all of them are very logical and in exactly the right places.

Do you match that or build on it?

Both. In some places you have to match that, especially in a place where there’s big moving pieces onstage, you have to pace the music so it synchronizes with closings or openings of certain things at some points, on top of all the classical details. I’m adding articulations, for example in the Pastoral, which is written in the way going back into, not Baroque music, but earlier than Mozart; at the same time it’s music-making by Lisa and Pauline, who are playing these Mozart-type arias at home, so for that, there has to be, from the orchestra, this way of playing “a la Mozart” in some ways in terms of style. On the other hand, you still need the feeling they’re trying hard but not professional musicians, as they are not in the libretto; they are, in the tradition of aristocracy, learning music for entertainment, so on top of this classical scene, it’s figuring out how to enrich and give to the audience this understanding of a whole type of music-making within the scene.

How much is your approach influenced by your recordings?

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1 is one of the most close to Mendelssohn and his territory – Pique Dame has this, a little bit lighter approach into the orchestration in general. During the recording cycle of the (Tchaikovsky symphonies) 4, 5, and 6 a few years ago I said to the orchestra, “Please, let’s not think of him only as this emotional, hysterical type – think about him as a man who spent actually at least three to four months outside of Russia, mainly in Italy, but also Austria, Germany, France – he opened Carnegie Hall!” He was a man traveling a lot and absorbing a lot of principles of other composers. And also there’s a lot of a German way of orchestrating in the symphonies and in Pique Dame. He used all the principles of orchestration of the time, he attended Wagner operas, he was a man who knew so much about the world tradition and that’s what makes him so unique; he had a pure Russian soul and a German way of orchestration, and that’s what I’m trying for in the symphonies, and in some places in Pique Dame.

Too often Tchaikovsky’s music is presented in just one way.

I think you can always find something new, even in the most played and performed score. I’m always trying to find the details, and get from the orchestra and singers something written in the score but probably obscured during tradition, because it is there you get to be very authentic. The devil is in the details, as they say.

Especially in this opera!

So true!

Will this lead to more opera for you then?

I hope to do more opera in the future than I was doing recently; I hadn’t done it simply because I was so busy with so many orchestras, but I hope for more productions in more houses.

And in-concert presentations also?

In-concert yes, we are planning a few things for 2020-2021… there are a few things, even some less-frequently performed operas but still great operas which are cooking at the moment. Stay tuned!