Photo © Marcus LIeberenz

Which came first, the concept or the opera?

This is the question I kept asking myself through Ole Anders Tandberg’s production of Wozzeck at Deutsche Oper Berlin. Having been frequently presented in Berlin over the past few years, this presentation is, admittedly, up against some stiff competition, but not having seen any of those stagings myself, I was going in fresh, curious if I might finally experience a production I liked. Alas.

Keeping in mind what I’d written about Claus Guth’s Die Frau ohne Schatten, and how Regie can and frequently does divide opinion, Wozzeck is one of those works that is divisive by its very nature. It invites abstract production because of its entirely abstract nature — the work itself, through its score and story and frequent use of Sprechgesang, resists the idea of tradition, purposely poking, prodding, and sometimes happily eviscerating the entire concept. Creative choices can sometimes thrive in and around such works, and yet, I have yet to see a live performance of Wozzeck that completely satisfies; alas, last evening’s experience at Deutsche Oper Berlin did nothing in altering this stymied state of music affairs.

Berg’s opera is based on the play Woyzeck, and though it was left incomplete by author Georg Büchner (who died in 1837), it remains a highly influential work, particularly within the German theatre world. So too Berg’s Wozzeck within a classical music corollary; even now, a century after its composition, the work remains revolutionary for its whole-hearted embrace of atonality. Solidly resisting all the predictable sounds and techniques which had dominated Western classical music (along with standard operatic forms) up to that point, the opera, written between 1914 and 1922 and premiered in Berlin, went on to enjoy immense success across Europe before it was labelled “degenerate art” by the Nazis in 1933. It is, as Britannica tidily puts it, “a dark story of madness and murder,” its titular character a soldier stationed in a town near to a military barracks in the early 19th century; an unfaithful wife, an illegitimate child, medical experiments, and murder are all part of the narrative which unfolds over 15 scenes, spread across three acts. It is, in a word, haunting; within Wozzeck‘s score can be heard the oncoming horror of the First World War, the breaking point of the social divides within late 19th century/early 20th century Europe, the desperation of people in an unforgiving place — physically, mentally, emotionally, financially, spiritually. It is a deeply affecting portrait of alienation, a trait various productions have attempted to underline, amplify, and explore, with varying results, since its first production in 1925.

Photo © Marcus LIeberenz

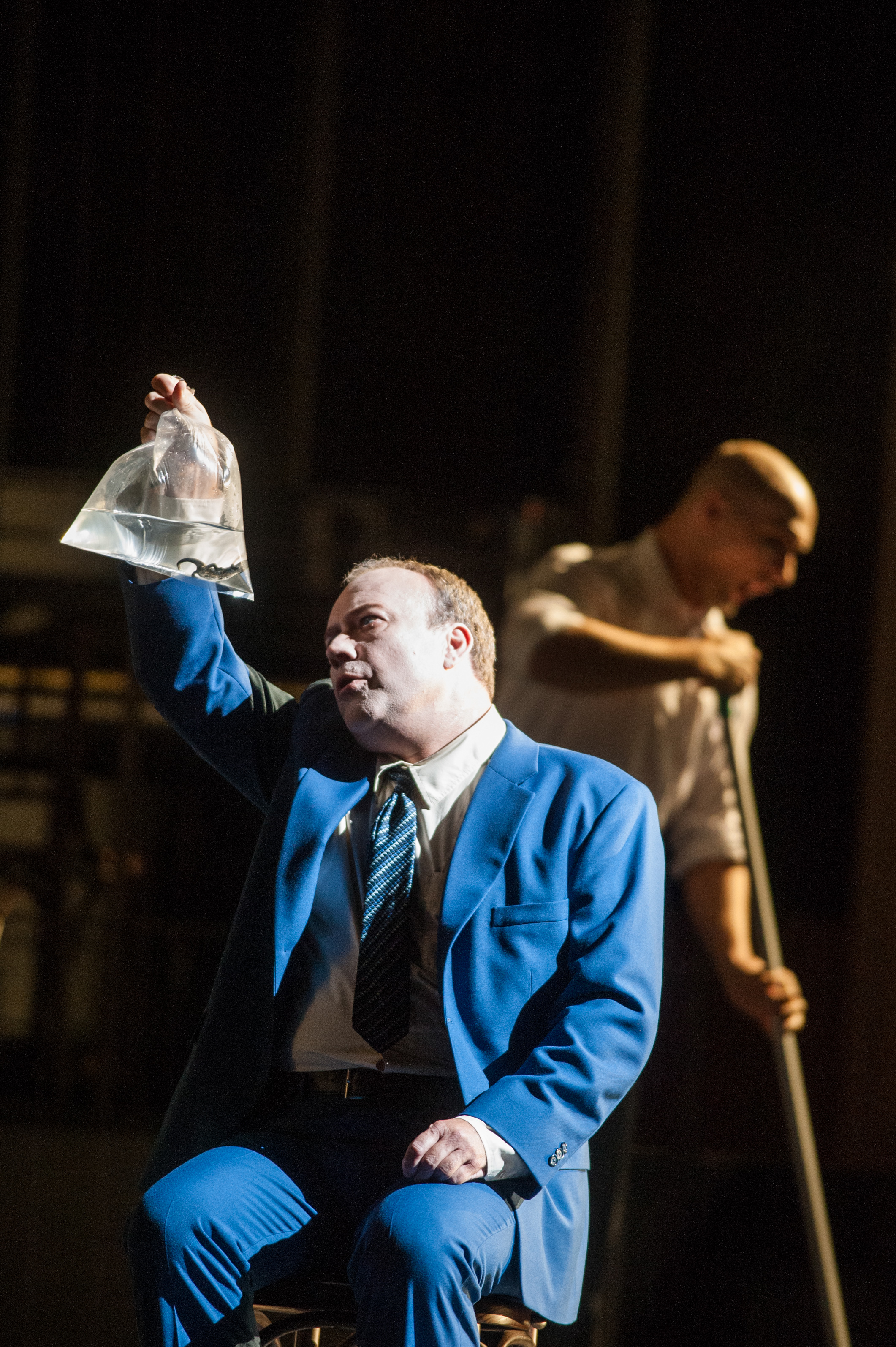

Tandberg places the action in the early/mid 20th century, in, as the program notes, the interior of a coffee house near the Oslo Royal Castle, on or around National Day in Norway, May 17th. The work opens with Wozzeck (Johan Reuter) and the Captain (Burkhard Ulrich) debating morality, though viewers will clearly note the line of soldiers with their pants down as Wozzeck tends to (ostensibly shaves) them; he later bends over for an examination himself. The carefully sterile set design, by Erlend Birkeland, reveals a precise geometry of repression, with square school-style tables in a canteen-like space framed by more boxes: a long bar, imposing doors and windows, where things are seen but remotely revealed, not even when soldiers can be seen frolicking and stripping naked. The scientific specimens the Doktor (Seth Carico) looks at through his microscope are projected via a tidy white circle upstage, which later drips with color, a display of fragility and cruelty at once. These are striking images, to be sure, but feel oddly distant to the work and its concerns. Those twin concepts — fragility and cruelty — and the way they interact, are vital to knowing and appreciating the life (inner and outer) of the central character, yet they are never explored. Wozzeck and the other characters are so smartly attired, it’s as if the subtext of destitution (so closely connected to that fragile-cruel dance) doesn’t exist at all. Surreal free-flows of ideas are fine, but the ones here have been placed not in service of the drama, but before it, which short-changes both the characters and our sense of them.

Photo © Marcus LIeberenz

This emphasis is most clearly expressed in the use of video. Tandberg, who previously directed Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and Bizet’s Carmen at the Deutsche Oper, presents each of the fifteen scenes that make up Wozzeck as pseudo-vignettes, tenuously (and tediously) divided by the closing and reopening of a black curtain, onto which is projected an immense, black-and-white close-up video of the face of its title character, blinking and silent. Rather than being an insightful and excitingly confrontational choice in tandem with the nature of the writing itself (since the work is, in fact, composed entirely of just such a series of vignettes), the technique becomes a frustrating and emotionally distancing distraction that kills the much-needed empathy for its titular character. The aesthetic of Tandberg’s Regie-heavy approach to Berg’s sensitive, sweeping score creates a paralyzing disconnect between score, story, character, and experience, destroying any hope for an integrated and satisfying theatrical experience.

It doesn’t help that musically this Wozzeck seemed over-dynamic and yet frustratingly gutless. Musical motifs for the Doktor, Captain, Drum Major (Thomas Blondelle), and Marie (Elena Zhidkova), while prominent, were not clear in delineating characterizations within Deutsche Oper General Music Director Donald Runnicles’s grey reading, which had an unfortunate and consistent tendency toward limpid tempos and lack of coloration. Wozzeck’s insistent motifs were jaggedly unfocused and suffered further by being diffused against a muffled orchestral acoustic. Any sense of vocal nuance baritone Reuter might have brought to form a more satisfying and complete characterization was washed out by the sheer volume coming from the pit, though baritone Carico, as a demented Doktor, and Zhidkova, with her plummy mezzo tones, fared better. The firmly Regie tone of the production, while brave, added little if any value to the experience of the themes of Berg’s opera. Alas, all was also washed out to sea, drowning in more than the blood that flowed, mercilessly, in the final scene.