Throughout my series of essays over the past three months examining various cultural, musical , and media-related aspects concerning the war in Ukraine, the one thing that seemed just out of reach was a direct view on the act of departure – or the act of remaining – from or in one’s place of birth. Recent events, most notably those around so-called “Victory Day” in Russia, have served to underline the changing realities around leaving and staying, in both tangible and intangible ways.

Russia’s list of émigré composers is lengthy; the reasons for their departure (and in some cases, return) relating to socio-cultural, financial, and political circumstances and opportunities. Perhaps the most notable Russian non-Russian, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) could only explore his culture through being away from it, not unlike his literary counterpart, the Ireland-born, Europe-living James Joyce (1882-1941). Stravinsky’s relentless curiosity and his willingness to experiment with elements of the Russia he’d left behind in various ways – milking, mocking, embracing, tossing aside those sonic elements, and surgically excising the clichés even as he sentimentally held on to their other, more personal aspects – feels, in retrospect, like a quilted instruction manual of artistic fortitude and spiritual survival. He is one of the composers examined in Music and Soviet Power, 1917-1932 (The Boydell Press, 2012), authors Marina Frolova-Walker and Jonathan Walker. The authors incisively feature a quote used by Soviet musicologist Yuri Keldysh (1907-1995), who is himself quoting critic/pianist/composer V. G. Karatygin (1875-1925), with relation to speculations on the roots of Stravinsky’s work: “The artist, while his art reflects a soul that has been splintered and corroded by neurasthenic impression, is fatigued at the same time by all this nervous tension and seeks out an antidote in the knowing return to simplicity.” Social relations, posit the authors, relate to this tension: “The less the facts of public life pointed towards hopeful outcomes, the more these demands were placed on art. Some strong and vivid external impulses were needed for this.” Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka, premiered in 1911 at Paris’s Théâtre du Châtelet, reflects a dualism which became more varied if concentrated in its expression once Stravinsky embraced his émigré status. Keldysh’s observations on the work’s symbolism hold modern echoes:

By way of contrast to the noisy, notley crowd, there is Petrushka, with his sufferings and his broken heart, expressed through his convulsive rhythms and angular melodies. A wooden doll, a mere puppet, turns out to have feelings too. We have an opposition here: on the one hand, an apparently lifeless puppet jerking mechanically on his strings but capable of refined and complex feelings, and on the other hand we have the living but soulless crowd; this opposition bore a social meaning that responded perfectly to the mood of the intelligentsia during the period of reaction following 1905. A complete withdrawal from active social struggle, a forlorn subjectivism, a dissatisfaction with reality – all these were expressed through the passivity of a moribund psyche, embodied by the image of the suffering Harlequin. The bright colours of Petrushka’s folk scenes, is thus only a superficial element that throws the inner psychological content into relief.” (p. 244-245)

The bright colours seen in recent news reports, as well as across the social media pages of various Moscow-living musical figures, might be viewed thusly, with the realities of those who have left the country making for a far more grim, far less click-friendly presentation. Writer Masha Gessen captured the contemporary experience of departure thusly: “The old Russian émigrés were moving toward a vision of a better life; the new ones were running from a crushing darkness. […] As hard as it is to talk about guilt and responsibility, it’s harder to figure out what the people who used to make up Russia’s civil society should do now that they are no longer in Russia.” (“The Russians Fleeing Putin’s Wartime Crackdown”, The New Yorker, March 20, 2022) It must be noted, of course, that there are varying levels of the experience of tragedy, and that no equivalency can or should exist between Russian émigrés and those fleeing Ukraine. In an exchange with Ilya Venyavkin, who is a historian of the Stalin era, Gessen makes this point explicit: “Now that this parallel society was gone, Venyavkin could think only of the future, which had become strangely clearer. “I refuse to look at this as some kind of personal disaster,” he said. “Disaster is what’s happening in Ukraine.” (The New Yorker, March 20, 2022).

These readings, combined with observations of the numerous concerts, benefits, and tours recently, have been powerful reminders of the ways in which people respond to trauma, particularly those within the creative sphere. Polish sociologist Piotr Sztompka wrote about such trauma in his 2000 paper The Ambivalence of Social Change: Triumph or Trauma? (Polish Sociological Review , 2000, No. 131 (2000), pp. 275-290). He expertly examines the coping mechanisms through which various traumatic situations and events might turn into what he terms a “mobilizing force for human agency” and catalyze “creative social becoming.” Aside from the fascinating examinations of the rise of moral panics (more on that in a future essay), Sztompka quotes American sociologist Robert K. Merton (1910-2003) in his four adaptations to anomie, a term with particular currency. Merton had postulated possible consequences to social strain, elements which could be experienced via the misalignment of individual or collective ambitions, and the circumstances in realizing them. These elements formed the basis of his famous strain theory, published in 1938 in the American Sociological Review. Piotr Sztompka (b.1944, Warsaw) adapted Merton’s ideas to cultural trauma thusly as innovation; rebellion; ritualism; retreatism, elements which he discusses at length in excellent paper, written a scant decade into post-Soviet life. I fully credit Marina Frolova-Walker for the introduction to Sztompka’s work; in an online lecture last month, she provided a wonderful introduction to these concepts within the context of her own post-Soviet musical analyses. It is the innovation aspect to which I am the most interested presently, one I suspect possesses the greatest resonance within the post-pandemic realities of the classical sphere. Certainly innovation (or its lack) is a concept relevant to the many new season announcements by orchestras and opera houses of late; just how those “reimaginings” will manifest, in light of pandemic and war, remains to be seen.

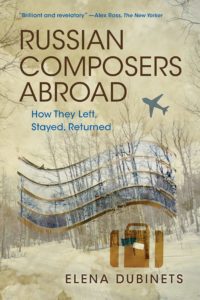

Thus it was that Sztompka’s ideas, together with the currently cautious cultural climate, that I was inspired to reread Russian Composers Abroad: How They Left, Stayed, Returned (Indiana University Press, 2021), by Elena Dubinets, with a fresh, curious view. As well as being an author, Dubinets is the Artistic Director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), a position she began in September 2021. A self-described Jew from Moscow with a Ukrainian spouse, Dubinets has a length and very impressive CV. She worked as Vice President of Artist Planning and Creative Projects at the Seattle Symphony Orchestra for 16 years, where she also played a central role in producing and co-founding the orchestra’s in-house label. The trained musicologist was also a Chair of the City of Seattle Music Commission (appointed by the Seattle City Council), a member of the Advisory Board of the University of Washington’s School of Music, and was Chief Artistic Officer at the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra before accepting her position with the LPO. A graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, Dubinets has taught in her native Russia, as well as in Costa Rica and the United States, the country where she and her family moved in 1996. Russian Composers Abroad: How They Left, Stayed, Returned examines the movement of both Soviet and post-Soviet composers within the greater paradigm of socio-political identities, ones which shifted and morphed, or not, according to geography and circumstance. Connections in and around these inner and outer realities are ones Dubinets takes particular care with; such investigations have pointed resonance to the current, perilous displacements and journeys being made by so very many. Utilizing a myriad of references and quotations from a variety of sources (including composers Boris Filanovsky, Anton Batagov, Serge Newski and Dmitri Kourliandski) Dubinets examines the 20th and 21st-century diasporic musical landscapes through wonderfully contextualized lenses of history, culture, finance, socio-religious beliefs and practises, and old and current politics, as well as the ways in which identity can and does change according to a combination of these factors.

In a Chapter titled “The “Social” Perspective”, Dubinets features an exchange she shared with composer Mark Kopytman (b. 1929-2011), outlining the cultural explorations and varied journeys which were seminal to his creative identity. Born in Ukraine, Kopytman graduated from the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory, and went on to work at conservatories in then-Soviet Moldova and Kazakhstan. Kopytman emigrated to Israel in 1972, where his ascent at the Rubin Academy of Music and Dance (Jerusalem), from Professor, to Dean, then to Deputy Head, gave him a unique perspective on his past experiences and then-current path. He told Dubinets that his understanding of his own Jewish roots stemmed from his study of Yemenite folklore, which led directly to various compositions integrating various histories and traditions. “Would Kopytman have developed his Jewish identity had he stayed in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, or Moldova? Most certainly not.” (p. 139) Dubinets also examines the important if often overlooked act of return. Given the current circumstances and the related antagonisms connected to speaking out against the war or not, these observations hold particular poignancy:

There is a heightened sensitivity among Russian returnees about the resentment they perceive to be directed toward them, and some clearly remember the antagonism and even discrimination they experienced when they came back […] Having studied the emigration-related consequences of the Balkan conflict, Anders Stefansson observed that relationships between emigrants and those who stayed behind often provoked the strongest outbursts of frustration and anger, even more than their memories of violence or the stigma of refugee life. The notion of Otherness and nonbelonging developed in these situations in relation to one’s territorial kin and the sense of former national unity did not guarantee welcome, tolerance, or even basic acceptance. Emigrants – many of whom later tried to return – fell from favor in the homeland and were treated as both social and cultural foreigners and national defectors. (p. 290-291)

The notion of “Russian”-ness needs to be re-examined, Dubinets posits, as she skillfully untangles the fraught web of Soviet and post-Soviet musical identities, and the twisting social connections therein. Her thoroughness and conversational writing style lend a cohesiveness that illuminates Eastern creative landscapes as well as those further afield; Dubinets puts her business acumen to good use in examining aspects of marketing, criticism, and “value” as ascribed to musicians across varying social fields, and related locales. This is a book of nuance, not of binaries, a timely work that moves past the noise of reductionism. Dubinets provides meaningful investigation into the realities of creative life amidst the current sea of both manufactured and real outrage, of profitable obfuscation and polemical thought, creating a myriad of vital understandings and illuminations of musical life, insights which are especially valuable in a time of war.

We spoke at the end of April (2022), about war, identity, and much else.

How do you see musical Russian musical identity now, especially within the wider umbrellas of socio-political and cultural shifts?

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “Russkiy mir“, in order to include any Russian-speaking person on the planet. This was striking for me to realize when I was beginning to do my research about the music of émigré composers: wherever they’d go they’d do Russian music based only on their language. They could be from Georgia, Estonia, from Ukraine of course, or from Russia, but wherever they were placed on the globe, the perception is that they were Russians.

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “Russkiy mir“, in order to include any Russian-speaking person on the planet. This was striking for me to realize when I was beginning to do my research about the music of émigré composers: wherever they’d go they’d do Russian music based only on their language. They could be from Georgia, Estonia, from Ukraine of course, or from Russia, but wherever they were placed on the globe, the perception is that they were Russians.

I have a similar story myself: back in Russia when I was studying at the Moscow Conservatory, I did a dissertation on American music, and when I moved to the U.S. and people realized I was speaking Russian and a musicologist, everybody who got in contact with me assumed I was a specialist in Russian music itself – and I was not. I had to slightly go with the flow, but it was an assumption that was quite often put on people and they became labeled with it. Typically this is what the current Russian government wants, and what they organized way before the war, in the late 1990s; Putin then strengthened it, but they organized these meetings of Russians abroad, so to speak, and created certain organizations for supporting the development of Russian culture and Russian music abroad. These associations were especially strong in the UK and they were run by Russian state organizations, so it was an intentional effort to broaden the scope of the government, and to put us all under the same umbrella, regardless of our differences. And it didn’t work, this idea of Russian culture.

… and now it’s biting many people back. Various forms of identity are part of the public discourse now, and identity politics, traditionally seen as being the purview of the West, are being applied in the very place that would resist them most. I wonder what you think about that, particularly within the broader scope of what is being programmed for future seasons? Valentyn Silvestrov (b. 1937, Kyiv), for instance, specifically identifies as a Ukrainian composer.

Well, there are ethnic identities, some want to change them, stick to them, become something else, not all want to be presented as Russian or Ukrainian. Silvestrov specifically wants to be considered a Ukrainian composer because this is his passion, this is what he dedicated his life to. Others will tell you, “I am a composer. I am not a Russian composer.” The same goes for women composers: “I am not a woman-composer; I am a composer.” And so… I’m in favour of people somehow identifying what they do themselves, rather than us putting them in a corner, and trying to label them with certain things that sometimes even we don’t understand. What is indeed “Russian”? It’s really hard to explain to those who are far removed from that state and culture, and for some of us, even the word “Russian” can be understood differently, because there are different words for it. One word can be translated to mean it’s a state-related identity, like Russia as a country-state – “We are Russians because we belong to the state in one way or another” – but another word can be translated as a cultural identity, a language-related identity, which would have nothing to do with the state. In my book I have discussed this concept, and the idea of cultural affiliation – it might be a useful concept to consider instead, to replace the other, much more questionable forms of national identification. What I mean by that is some people simply can’t or don’t want to be singularly associated with the state, or another state, not just Russian; it’s an idea which is applicable to all countries. You might have seen the names in my book, composers like Tszo Chen Guan (b. 1945, Shanghai), who is from China, or Lantuat Nguen (Nguyễn Lân Tuất; b. 1935, Hanoi), who is from Vietnam – they learned Russian, it’s not their first or even their second language but they moved into Russia, and became Russian citizens. And for that reason they had to be affiliated with that specific culture and learn how to accommodate its main stipulations. They started writing Russian overtures and Russian symphonies, and went on to other cultural affiliations. So there is a way to be attached to a country even if you are not really born there.

What I’m trying to conceptualize is that the binary concepts of inclusion vs exclusion, belonging vs otherness, acceptance vs intolerance – these concepts are becoming outdated because the world has changed so much. We are on the move; we are learning new cultures. And we want to be considered as individuals rather than attached to any identity politics.

Context moves against those binary notions, although the nature of contemporary publishing is such that context is thrown off in favor of binary thinking, because it means more clicks, more views, immediate reaction; outrage. I was thinking about this when I read Kevin Platt’s op-ed in The New York Times, which made me consider composer Elena Langer (b. 1974, Moscow), whose work you write about and have programmed as part of the LPO’s 2022-2023 season. How much do you think the idea of redefinition matters? Redefinition moves against binary reductiveness, but it requires flexibility to implement. How do you cultivate that?

I think after the pandemic we have received this very unusual level of flexibility – because we had to change everything for two seasons and we had to do it on the fly, according to each situation. This season we had at least five weeks in a row when we had to make considerable changes in our programming for multiple reasons, not only covid-related but we had a storm – there were all kinds of things, and one of them was the war. For me this ability to change programming and to change, to react to the surrounding world, is absolutely necessary. I have always been troubled by the inertia of arts organizations, and particularly opera houses and symphony orchestras; we have to plan very early, at least two to three years out, and with the opera houses, it’s even more, it’s up to five years out they plan, and that’s in order to ensure availability of composers, singers, directors, conductors – everybody possible – but covid changed all of it. All the plans got shifted. Organizations are still rescheduling and will be accommodating those whose performances got cancelled during covid, for a while, but priorities are also changing, so now I’m asking myself: what should I prioritize? A piece by a Ukrainian composer or one that was cancelled during covid? I’m enjoying the flexibility this time gives us because the audiences expect that kind of flexibility; they got trained by cancellations, which is a strange thing to say. We’d print our brochures and send them out in the “before times”, and we’d stick to what was in those brochures for the rest of the year; this is what people expected from us and we were proud we could satisfy their expectations. But it all went astray, and now if I ask somebody, “What concert are you coming to here next week?” they often get confused – the programmes have been so regularly changed. And that’s the beauty of the situation, this is terrific actually, because we can swiftly implement something that hadn’t been in the plans but can be responsive to the moment.

I wonder if that relates to the first facet of cultural trauma as outlined by Piotr Sztompka, innovation, a concept that feels especially important now. Your choice of quotes from critics in both North America and the UK in your book made me wonder how much innovation does or doesn’t travel across the ocean, particularly post-pandemic.

It’s coming, slowly! It’s much much slower than what we are used to in North America, and I’m still struggling with the fact that sometimes I have to explain very simple things to my colleagues in London. They didn’t live through BLM (Black Lives Matter), or, they didn’t have a similar experience of it; that time was a very, very different thing for them. It was mostly distant; music people here heard about it but didn’t internalize it. In the States it’s impossible not to think about it, but in the U.K., it’s largely, at least in the cultural sector, “Oh right, that.” It is slow to get it into the fabric of our thinking about classical music, and you know, we need a number of pioneers who will lead the way, like for example, my orchestra has been working closely with the Association of British Orchestras (ABO) – they are definitely leading the way, they know about BLM and what they should be doing, but you know, they need to continue convincing the constituents. There are other organizations the LPO works with who are educators, they are groups who are very passionate – they don’t do programming themselves but work with the institutions who do. So I think the more of this work there is, the better it will be. The consensus exists that change has to come but they haven’t gone through things yet.

The UK is much more attuned with the concept of sustainability, however. People use public transportation here more than in North America. There, my team was trying to consider what could be done in terms of greener orchestra attendance, and because everybody uses cars it’s just not possible, but really, it’s one of those things we have to think about. It’s what we do, after all, it’s a life form – people have to physically attend – and In the U.S, to do so they have to drive, whereas in the UK it’s much more about trains, even when we’re on tour. We work with venues on certain aspects of that much more so than counterparts in the U.S. do.

One thing I appreciate your acknowledging during the recent LPO season preview recently is the overall insularity of the classical music world – “our small and somewhat isolated classical community” as you put it – but do you think that bubble is breaking up now, however slightly?

We’ve been observing a pretty interesting process here, but sadly we still can’t qualify it. What we’ve noticed this season, when we came back with the first season of live performance after the pandemic, was that many people got used to watching us online, because we had organized a major series of concerts. We streamed 35 concerts online, the same number we’d normally perform live at the Royal Festival Hall. People were receiving it in the comfort of their homes and they got used to it. Many say it’s a very different experience than when they come for live concerts, that they get something else, they get a different type of engagement – but not all of them decided to come back (live). Some of them are still worried about their health; some live too far away; there is a constituency that hasn’t returned.

However, there is a completely new group of people and it’s mostly younger people who show up randomly at our concerts. We always understand how many are coming, it used to be so subscription-based that we’d know a year out how many would come, but it’s not the case anymore; people really don’t buy until the last minute now, but they do come and they are extremely enthusiastic A recent concert with Renée Fleming is a good example. Of course she’s a star, but it felt like a rock concert! People were screaming, they were young people too – it was stunning for me to see. I’ve worked with her before, in many orchestras, but it was a totally different planet, this concert. So I’m constantly asking myself if this is what we are getting because of the covid and the streaming, if this is why people are so much more embracing of programming changes and of new music and of things they’ve not heard before – I hope this is the case. I do hope we have obtained new audiences somehow after the pandemic, but we still don’t have any statistical data.

I had a conversation with classical marketing consultant David Taylor recently and we discussed how low prices do not inspire younger audience attendance – it could be free but they wouldn’t go – it’s the experience itself, of offering something that can’t be had online.

I totally agree, and I know things we’ve learned about, that we understand what may or may not bring them in that regard. We had an Artist-In-Residence this year, Julia Fischer, who did all five Mozart violin concerti, and we had half-houses for all these concerts. Now if you asked our marketing department three years ago about this they would have said, “That’s a definitive sellout, continue doing only this stuff and then we’ll be all set with our budgets” – but people didn’t show up this time. They showed up for some random and obscure performances we hadn’t budgeted for accordingly, so yes, they come unexpectedly. It’s hard to understand at this point, as I said.

That’s part of the innovation aspect with relation to the cultural responses to trauma, seeking new experiences after two years of watching behind a monitor, although there are many who still choose to do so, whether because of economics or health, or a combination of both. It behoves many cultural organizations not to take those audiences – or how we choose to enjoy concerts – for granted.

That’s true – it’s why our goal with programming has been and will remain in balancing our repertory and offerings; we know that younger people are predisposed to new things and older people mostly prefer their blockbusters, and we’re also going back to the habit of explaining musical experiences – that is, our conductors speak from the stage. I want to say that for almost a decade such a thing was considered a no-go: “Music should speak for itself,” many would say. But now people seem to have the desire to learn more, and how do you learn if you have all possible restrictions? I’m always annoyed the lights go down during performances to such an extent it’s impossible to read the program books – you just can’t see them – and also the small type is very unfriendly. On the other hand younger people can open cell phones and read the notes online but it is too bright in the auditorium to do that, and we make a point to tell them they can’t use their devices during performances. It is an unfriendly art form in many ways when it comes to educating people about music and educating them about the experiences they have paid money to hear, so we are now beginning to talk more openly about doing pre-concert lectures and doing quick introductions from the stage right before the music. Of course we’ll be using digital means going forward as well, that’s important, we really want people to come back! They vote with their feet, and if they don’t like something, they don’t come back.

But you are also filling in the holes for an education system that has been continually underfunded over many decades. I am not sure all classical organizations themselves think of their mission this way; I recently read about a festival featuring the music of Rachmaninoff and the language consisted largely of clichéd notions of “Russian” music. Is this, I thought, how we should talk about him (or any Russian composer) anymore? It seems so outdated.

We played Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony on the third day of the war – that concert was called “From Russia With Love” and consisted entirely of Russian music: Prokofiev’s Second Violin Concerto and Rachmaninoff’s Second. I actually had to go onstage and say something because it was unimaginable to do the concert without any framing of it, without putting it within the current situation, whereby it could have been just cancelled outright. We could have done just that, but people bought tickets; they wanted to hear this music. Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) has never associated himself with Putin, and I thought, “Why would we cancel it? We just have to position it properly.”

So we played the Ukrainian national anthem to open, after I said a few words, and really, this is what it means to be relevant as an industry: it means engaging with people’s emotions and thoughts in a particular moment. We played the anthem at a time before everyone else was doing it. I explained how Prokofiev (1891-1953), even though he is considered Russian, was born in Ukraine, specifically in the territory being bombed at the moment; as to Rachmaninoff, he left Russia because he never agreed with the regime change or its policies. Putting the music in context makes a huge difference in people’s minds…

Context, the magic word!

Yes! And we had a standing ovation after the anthem, and it wasn’t a standing ovation for only how well they played this music or how beautiful it was or is; it was a standing ovation for the fact we decided to open a concert with, let’s use this word, a “dangerous” program this way, by explaining what it means to us and why we are doing it.

I asked Axel Brüggemann about this recently and he agreed but added that such contextual information can sometimes disturb people’s closely-held perceptions of beauty in art…

So maybe he’s thinking of Dostoyevsky’s idea that beauty will save the world… and we know it will not!

It’s interesting you mention Dostoyevsky because there have been numerous discussions pondering if he should still he be held up as “the great Russian writer” considering his anti-semitism. Rather than knee-jerk reaction, my instinct as a teacher is to examine his work with full contextual awareness, which might lead, as your book also suggests, to a rethinking of greatness, of Russian-ness, and how we use the word “genius” going forwards.

Yes, and what I tried to always state and intimate, when I can, is that Russians are very different, Russian music is a part of the Russian image, the government has used it to its own narrative, but we must never conflate all Russians, and especially Russian composers and musicians – and artists in general – into something unified. It would be anachronistic and inaccurate. In that op-ed you mentioned, Kevin Platt was trying to do this, and I don’t think it came off right, especially since he placed Gergiev and Netrebko in a strange context – but he did say Ukrainians who write in the Russian language, they certainly self-identify as Ukrainians, but they still use the Russian language, the same way as Gogol (1809-1852) did in the 19th century or Shevchenko (1814-1861) as well. They did it because Russian was the language of the empire, it was a colonizing language, and actually moving to Saint Petersburg was because of the opportunities that existed there, ones that didn’t exist for their art in Kyiv or in Ukraine in general.

We can never forget about the social element and infrastructures of how the arts are done when we examine any art form, especially music, because it is an extensive art form; you sometimes have to hire hundreds to perform your piece, and how can it be supported if the state or major donors don’t invest in the art form? We can’t forget about that reality. Some Ukrainian writers simply had opportunities in Russia, and when Russian had become a terribly universal language for all citizens of the former Soviet empire, they simply continued using this language – but that doesn’t mean they’re Russians; we can’t conflate them all into the same plot . For this reason we can’t cancel it all; we should perform it. People like Gergiev… no, that’s different. It’s clear to everyone on the planet I believe, that he specifically benefited from this government and specifically supported its war efforts; many others have not, they protested, it should also matter and it should count.

Having said that, I have experienced opinions from other folks, for example Ukrainian musicians, who think that while the war is ongoing, Russian and Ukrainian music shouldn’t be on the same platform or the same programme, and while I don’t quite agree with it, I do see the rationale for that, and I understand their position. Ultimately what they’re saying is music is their weapon as well, the same way it is and has been soft power, and a soft weapon for the Russian government, so Ukrainians are also saying, “We have this meaningful tool and we want to use it appropriately.” But there is also another element bothering me recently as a scholar of Russian music and culture: I agonize over the fact that right now is not an ideal time to advocate for Russian music, but it is impossible to reconcile the unimaginable atrocities that have been committed by Russian soldiers with the fact they were educated in school studying Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, and Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. They were part of the system and even if they didn’t internalize it, it was there, it existed. I know myself, I studied and taught there, and know how it’s done right now. So it’s hard to understand how people who had at least some cultural background and education in school, do what they’ve been doing…

Quite a few reports have explored the connection between military service and poverty, and President Zelensky has noted this also, which makes me think that for all culture they were shown in school, it doesn’t mean the same thing for them as it would for others in different areas. What is culture if you have nothing in the fridge and no job prospects outside the door? This makes me ponder our role(s) as artists / thinkers / writers / producers / programmers of culture, and of how to create or support a system that reaches past our bubble – which goes back to your points. The classical community needs to start thinking about all of this…

… we do have to, yes, but unfortunately right now the domination of the Russian government there, in those places, is remaking the ways in which school kids, those in elementary schools, will be studying history and culture, and also unfortunately, that history and culture will now become even less based on facts and even more based on ideology. This is the reform they’re initiating right now as we speak. So who will grow up within that system, between ten to fifteen years from now, is scary to imagine. And that’s not talking only about rural areas but cities as well, because they all have the same agenda, to glorify what the army is doing right now.

The language for that glory creates and shapes a reality which is not, in fact, reality – but surely this is why we have to talk about culture, and characterize decisions in culture, very carefully ourselves, and make sure when we make these decisions public or engage in exchanges that such language is very precise and not reactionary…?

Yes, and we should do that. In Russia that sense has been killed; what exists is public television which is a very determined agenda. And going back to what you asked me about what we learned as a result of the pandemic and how Europe is different from North America: Russia is an entirely different planet. They’ve never heard of some of the concepts we are trying to implement, or they are totally against them. They are not even trying to understand or accept the realities of the current time. If you are talking about diversifying the art form, they’re never considered this. I’m worried this feeds into the overall line of the “exceptionality” of the Russian culture in general, and that idea applies to Russian musicians in particular. They don’t want to accept that there are other cultures, other important elements in our world that they need to consider.

That’s an important point, this notion of Russian exceptionalism, which has existed in parts of the Russian classical world for a long time I am not convinced such an attitude is good for art, or for people. Journalist Maxim Trudolyubov tackled the topic of Russian exceptionalism in the arts in a newsletter which attracted immense pushback from Russian artists, if also support from certain musicians, including composer Boris Filanovsky, who you quote in your book.

You know it’s always interesting to consider how decolonization should happen, and quite an obvious way would be for those formerly colonized cultures to be considered independent of their colonizers. This is what I am observing right now: I think the deconstructing of Russian imperial identity is happening in such a way. Ukraine has always been positioned in comparison to Russia, and Ukrainian artists are often compared to Russian artists. I’ve heard here, on my job with the LPO even, on multiple occasions, that we don’t know Ukrainian music because “Oh, it’s not as good as Russian” – and this is silly. People don’t know Ukrainian music, period, because it was purposely colonized that way, it was undermined by the occupier, by the empire, by its ambitions for their counterparts who would willingly point it out to everybody, that what they do is better than what other people in the provinces do, and Russians just don’t want to hear this piece of history, we completely ignore this societal argument. So when decolonizing these cultures, say, Belarusian or Ukrainian, I think they should be able to stand on their own rather than being constantly compared with Russians – and right now the public discourse is such that it’s just not happening. Maybe a few more months have to pass. Right now our goal is to perform as much Ukrainian music as possible and convince everybody it does stand on its own, and that it does have this individuality which it was not granted in the past.

So it starts with those programming choices and the flexibility you mentioned and saying, “Yes, we are going to have this composer and that composer in our programme tonight, it isn’t announced, but here it is” – just that spontaneous?

It’s just that. We performed a piece for violin and orchestra, “Thornbush”, by Victoria Polevá (b. 1962, Ktiv) at the fundraiser for Ukraine in Glyndebourne in early April; it was not really announced but we spoke about it from the stage, and then we decided to commission a new piece from her for next season.

Our entire 2022-2023 season will be dedicated to music by composers who had to leave their own countries as refugees to displaced composers – so we’ll talk about issues of home, what is home, what is displacement, how the composers experience exile, homelessness, despair, when and why they had to drop everything and leave – and what does it mean to “belong:, in a much broader sense? Is the idea of “home” just an emotional environment they wanted to create for themselves? Or is it a certain geographic location? Is it a time and place? There are so many possible descriptors of what “home” is, and this is what we hope to explore through music next season. The idea of this season came up when I was just hired to become the Artistic Director, about a year ago, and we thought we were implementing it pretty well, we incorporated composers who had left Soviet Russia or Nazi Germany but also Cuba, Afghanistan and Syria, and you’ll hear music from all these composers although few know their names. We had to make some choices in favour of these composers instead of programming Beethoven, let’s say, who could sell us many more tickets – but we used this new season to represent our general mission. And unfortunately the idea became – I say “unfortunately” because I wish this war never happened – very relevant when the war was starting, so we commissioned Victoria Polevá, who was on the way from Kyiv to Poland to escape the bombs at the time we asked – and so she will write for us next season. This is how I understand the mission of our art form at this terrible moment: decolonizing the preconceptions about classical music.

What was the process for recording Zingari amidst pandemic?

What was the process for recording Zingari amidst pandemic?

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical  DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (

DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (

So what a treat it was, to come across the album

So what a treat it was, to come across the album  As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “

I think the definition needs to change – it needs to be decolonized, yes. How we do it is a different story. It will take many generations, I’m afraid, to bring it to something different, because the definition is so established in our minds due to the fact that the idea of Russia as a whole has been perpetuated in the hands of successive governments, not just the current one but prior ones. They made that cultural identity a soft weapon for the country, and the Russian world, so to speak. I’m not sure if you speak Russian, but there’s a term that’s been widely used by Putin’s government, “

Reading your article I was struck as to why arts journalism isn’t conducting these kinds of investigations during a war in which so many cultural figures – and organizations, and programming – are affected.

Reading your article I was struck as to why arts journalism isn’t conducting these kinds of investigations during a war in which so many cultural figures – and organizations, and programming – are affected.