Every morning amidst sips of strong coffee and self-exhortations related to baking (because a piece of good white bread, toasted, is suddenly so much work), I examine a raft of newly-arrived emails, skimming this one and that to distinguish the urgent from the not. Some of the messages contain links to videos, some feature video and audio material embedded within; some link to longer features at a formal website, some hold lengthy features within the boxy confines of the message itself, ribbons of rich text snaking down like bits of untidy morning hair scattered around shoulders, glinting in the morning sun. Some contain good news; most don’t. Another sip or two of coffee, a sigh, a look out the window, past the brick wall of a tiny garden to tree tops poking proudly up in the distance; the sight is a vital reminder to try and see a better, broader picture amidst the far more limiting and depressing immediate one. At certain times perspective is indeed the most vital thing – but sometimes it’s just as true that a bad view is simply a bad view, a bad location is a bad location, and that certain changes are quietly if firmly asking to be set in motion.

A favored activity of late is watching panels featuring figures who are speaking outside of their immediate and respective comfort zones. One recent such event featured violinist Nicola Benedetti hosting classicist Mary Beard, mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill, and psychiatrist Raj Persaud; it was refreshing to experience such varied points of view about music and its effects; hearing Beard discuss Plato and his notions of music was a wonderfully bright bit of non-musicologist counterpoint. Another recent conversation featured conductor Alan Gilbert chatting with fellow maestro Herbert Blomstedt, a figure one might assume is not wholly used to speaking about music on Zoom. His jovial (and sometimes lengthy) hums of portions of Beethoven’s Third Symphony inspired, at the time of their delivery, a grab at the score off the shelf, and a mental note to devote energy to further examination – but oh, the humming was charming, a warm expression of humanity behind brilliance. I am presently looking forward to listening to Opera Holland Park’s Director of Opera, James Clutton, exchange views and insights with Komische Oper Berlin Intendant Barrie Kosky. Such offerings, together with concerts broadcast on various international radio channels, have been effective at not only filling in various knowledge gaps, but in allowing a needed experience of community amidst the continued quarantine isolation resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, and there’s a great worth in to such activities, one which needs to be recognized, for the pseudo-normalcy such material provides is at once comforting and enlivening, even as concerts in certain locales, under strict conditions, continue to resume. The sound of applause in Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche following Daniel Hope’s recent broadcast from the historical locale was gut-wrenching to hear through computer speakers, a happy if equally awful reminder of separation, communion, presence and absence, of a circle slowly being closed but revealing a yawning hole at its core, one that asks a nagging question: who’s being paid?

It’s a question being asked with more persistence as horrific economic realities settle in. Recently I took part in a Zoom conference which connected neurological reaction with online classical presentation, organized by the University of Oxford in collaboration with HEC Montréal (the graduate business school of the Université de Montréal). Numerous participants eagerly discuss their unique experiences (virtual and not) before discussion invariably turned to money: funding models, proper remuneration, the psychology inherent within the act of paying. One user subsequently commented that “I’ve found that I can really find any (event) online and for free, pre-recorded. However, I am much more likely to fully participate if I’ve had to pay a fee and strangely feel as if it’s of higher quality (untrue!). So that investment and ‘live’ element are crucial to me as a value indicator.” Observing the tide of rising doubt around online freebie culture has been interesting if somewhat painful, because it underlines the ugly and (for so long) taken-for-granted reality that writers, especially those with an arts beat, have faced for so long. My mother used to excoriate me for taking free work, when, still in my toddler-scribe stage, I would busily contribute to numerous large (and occasionally well-known) sites. “You’re giving away your talent,” she would say with exasperation, “to people who could well afford to pay you something. Just because they don’t know how to do business, you shouldn’t be the one helping them for nothing.” I would outwardly agree but feel inwardly trapped; was I really getting nothing? The choice between providing free work (which I wanted to believe opened a myriad of professional doors) or struggling in relative obscurity seems like a false one… and yet. The glittering of the promise of the internet, for a budding writer, depends so much on how willing one is to wade through a deep, dank swamp, for a very long time.

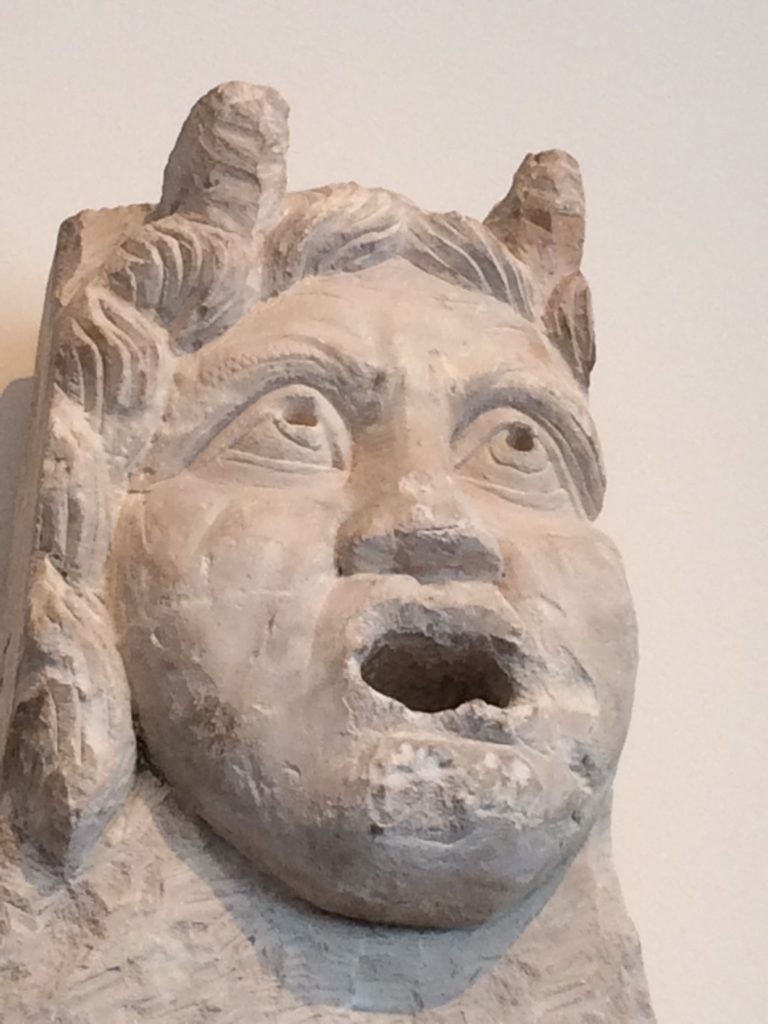

Water Spout Depicting Pan Or a Satyr, 2nd-3rd century AD, limestone; Altes Museum Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

That swamp became so deep through the immense devaluing of professional arts writing decades ago via the rise of digital and the related media/ad-tech/management decisions accompanying that ascent, decisions which still resonate and seem frustratingly entrenched within the media industry. As a writer, it’s terrible to feel consistently undervalued; it’s equally disheartening to continually donate your talent to large, faceless organizations without any form of reciprocal remuneration or recognition. I suspect, this is one reason why there are so many independent arts blogs in existence: people want an avenue for their passions, a place to share and sharpen and connect. The blogging world’s role and wider value within the classical ecosystem is a post for another day, but suffice to state here it is a world which bears contemplation, nay scrutiny, in direct relation to the concerns artists now express around the fairness (or not) of freebie culture. Awareness of individual value means retaining some measure of control over public offerings, which therefore necessitates the wilful exercise of choice in the implementation of remunerative properties. According to Buddhist belief, money is a form of energy, and as artists, it seems more important than ever to, as a 1996 article in Tricycle notes, “learn to ride this powerful energy, instead of being ridden by it.” I started this website in 2017 as a labour of love; its material, produced solely by yours truly, remains free for readers because it feels right to do so, as befits certain perceptions of me as an ambassador for music and the classical arts, which I am truly flattered by, but also take seriously. (Hopefully I don’t sound unbearably pretentious stating this.) I would far prefer to keep the unique value of that independence, in its myriad of forms, to myself, and carry my wonderfully faithful readership in that spirit, than give any bit of it (and me, and them) away.

The scribe Tjaj in front of the god Thoth, patron of scribes, in the shape of a baboon, Egyptian, 1388-1351 BC, wood & serpentinite; Neues Museum Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

That means any residual anger at the boss is worked out in front of a mirror, and whatever exposure (that infamous word) I gain is that which I am able to fully control, measure, and reinvest in and around pursuits and goals related firmly to gaining a broader perspective, for me, for the artists who interest and inspire, and for readers. I realize this isn’t sexy to advertisers, much less large swathes of music lovers, very much less the intelligentsia-musicology crowd I confess to sometimes feeling I need validation from. (Newsflash: writers are insecure.) But if there is to be any momentum in the classical ecosystem now, it behoves all of us, at all levels, to start thinking more carefully about ideas around exposure, exchange, and innovation. The notion of “giving” exposure to artists who produce cultural material for wide consumption across digital platforms in lieu of payment, by large (or even not-so-large) organizations needs to be more broadly and boldly questioned, for it calls into consideration the whole idea of how we, individually and collectively, think of culture and its role in our lives. A powerful recent editorial in The Guardian and today’s dire (if not unexpected) announcement from The Met force issues of cultural value to the fore. Should we care about culture in a time of pandemic and suffering and social unrest? How much? Is culture (and its related written coverage) perceived as a leisure pursuit? An escapist activity? A pleasant diversion from Real Life? Should artists be giving songs, shows, concerts, ballets, paintings, plays, and poetry (writing) out of the sheer goodness of their hearts?

Amidst the sudden closures and cancellations that took place in March there was an intense whirlwind of sudden online activity and free offerings from classical artists, a panicked logic that shrieked the understandably obvious. Large outlets with paid models (The Met, the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall, Wiener Staatsoper, Bayerische Staatsoper) were suddenly giving work away, standing, rather bizarrely, toe-to-toe with choirs and freelance musicians who were willingly performing from balconies, living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchen tables, suddenly grappling with cameras, microphones, angles, lighting, and the interminable joys of uploading, trying to balance self-promotion with communal experience and needed connection while ensuring their presence in a piece of unprecedented history. There was a wonderful and refreshing underlining of personality in some quarters. Lisette Oropesa’s warm exchanges, and the vivacious work done by Chen Reiss (for online interview series Check The Gate), for instance, revealed them both to be the plain-speaking, earthy sopranos I conversed with in respective past chats. I suspect many classical artists enjoyed (or are still enjoying) the experience of a quite literally captive audience, a heady and unusual mix of accidental and intentional, and why not? In those early quarantine days, keeping access free was not only a nice gesture but vital for business.

Wigmore Hall. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

Nevertheless, with the current resumption of concerts in some places and continued quarantine in others, the virtual is becoming tied to the real, the fantasy of a past normalcy tied to current financial reality. Desperate times call for stark if/then mathematics: if you want this album, then pay for it. If you want that performance, then pay for it. Artists are realizing it can be difficult if not impossible to put the toothpaste back in the tube once a precedent for free content has been established, with related expectations for its continuance. I strongly suspect certain events are about to have paid models applied to them, in various forms. Zoom conferences, like the HEC one I participated in recently, will, sooner than later, become paid events. Would I pay to watch/listen to a panel featuring Benedetti, Cargill, and Beard, or Maestros Gilbert and Blomstedt, or Clutton/Kosky? Yes. Wigmore Hall has just resumed weekday performances, with broadcasts (online, radio) in collaboration with BBC Radio 3, but one wonders what will happen after the end of June; will there be a paid model? The Berlin Phil’s Digital Concert Hall has returned to its own subscription-based service, while many opera houses are currently offering limited-run broadcasts of past productions. One wonders about all the discussions taking place around offering new models that might allow greater user flexibility and personalization of (especially live) experience. Crow’s Theatre in Toronto recently offered a (delivered) gourmet dinner from a local restaurant with a live presentation of their theatricalized staging of Master And The Margarita, all for a set price; Tafelmusik has paired with a local gelateria for their at-home listening experiences. Conductor Vasily Petrenko, in the most recent edition of his (excellent) Lockdown Talks series, flat-out asks Jonathan Raggett (Managing Director of the Red Carnation Hotels chain) if he thinks a future partnership between orchestras and hotels might be possible in terms of chamber presentations in conference/ballrooms. Everyone is madly examining the possibilities of alternative revenue streams with this, the new normal of cultural presentation and experience, even as we try to absorb what feels, many days, like a never-ending stream of shock and sadness.

At the Berlin Philharmonie. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

The ugly reality is, after all, that many outlets and individuals are facing bankruptcy. Nimbleness, while lovely as a concept, is not something easily, quickly enacted or adaptable to many lives, and exposure, or even its promise, does not (as so many writers know) pay bills/rent/mortgage, much less provide the stones that could line the pathways leading to such dreamed-of stability – but the promise of exposure is a terribly tempting, a solid-looking thing to hop on (equally so the “tip jar”) that is proving itself to be naught but a rusty anchor with one clear direction. The question remains: what are we willing to pay for? How does spending relate to the (vital, right now) notion of scarcity? What value do we place on the experience of community? It behoves artists to stop being squeamish about openly discussing proper remuneration, just as much as it behoves us to start considering the broader ecosystem that allows this form of energy to fully flow – an ecosystem that surely includes the written word as much as the sung note, as much as the open string, as much as the pressed valve and held tone. Certainly it can be intoxicating at seeing one’s work enjoyed and shared by many, in revelling in attention and praise; digital culture exacerbates this attachment, and indeed it is sometimes an energetic black hole of a swamp one might choose to never leave. But it is vital to know when one is able to walk on stilts, and to trot away proudly, not looking back.

Lately I have experienced tremendous doubts about this website’s continued existence, ones specifically tied to my overall worth as a writer. If I’m not getting paid by a big mainstream outlet, do I have any real worth? How can I possibly compete with intellectual types who have the backing of far larger organizations and fanbases? Do I have anything remotely worthy to contribute through my writing or other creative efforts? Would that feeling be altered were I to receive remuneration, or what might, in Buddhist terms, be called reciprocal energy? Should I cease public writing entirely? I keep looking up to the treetops, trying to imagine a clearer, better view. Notions of worth, value, and self-doubt are things everyone in the classical world grapples with at the best of times. Perhaps more thinking, more coffee, and a higher pair of stilts are required. Perhaps it’s time to find a better view.