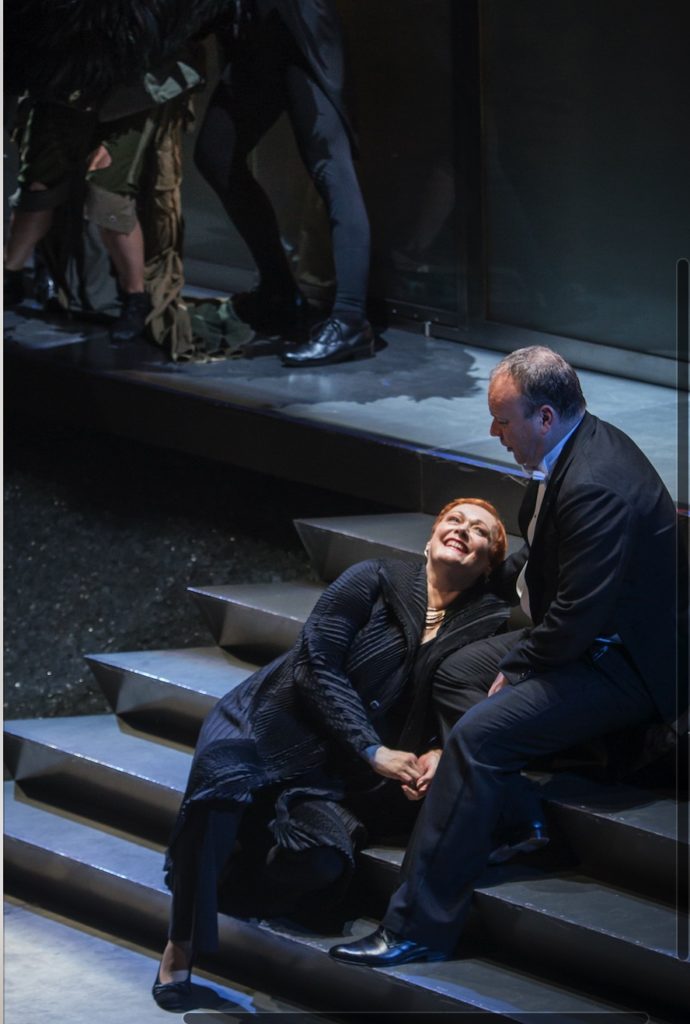

Photo © Sim Canetty-Clarke

Speaking with someone before a global pandemic and again after (or more accurately during) it is a very interesting experience. All the formalities drop away; the predictable edges of topics become rounded, blending into one another. The optimism and hope, gleaming like jewels in sunlight, have, over the past three weeks or so, been burnt into ugly despair, that gleaming dulled into desperate, leaden sadness. Everyone is hoping for a swift resumption to normal activity, but of course, the question right now, more obvious than ever, is what “normal” might look like then – indeed, one wonders now, in the thick of it, what “normal” is and what it means for life both in and outside the classical realm. We are all adjusting ideas, expressions and experiences, as creative pursuits, social activities, and bank accounts yawn steadily open.

Allan Clayton had been set to make his role debut as the angry Laca Klemeň in a new production of Leoš Janáček’s most famous opera, Jenufa, at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden (ROH) earlier this week; roughly ten days before opening, the production (and all ROH activity) was shut down. The tenor’s next engagements – in London, New York, Madrid – are still on the books, but as with everything in the classical world right now, giant question marks hang like immense, heavy clouds over everyone. On March 30th, Wigmore Hall cancelled the rest of its season; Aldeburgh, for which Clayton was to serve as Artist-In-Residence this year, is likewise shuttered. It remains to be seen if Clayton will get to sing a role he’s become associated with, that of Hamlet. in Brett Dean’s 2017 opera of the same name; performance is still set for June with the Radio Filharmonisch Orkest under the baton of Markus Stenz. “To be or not to be” indeed.

Clayton has a CV that leans toward the dramatic, as befits his equal gifts within the realms of music and theatre, with experience in Baroque (Handel), French (Berlioz), German (Wagner), and twentieth-century work (Britten), alongside an admirable and consistent commitment to concert and recital repertoire. His varied discography includes works by Mendelssohn, Mozart, and of course, his beloved Britten, with his album Where ‘Er You Walk (Hyperion), recorded with Ian Page and The Orchestra of Classical Opera, released in 2016. It is a beautiful and uplifting listen. A collection of Handel works originally written by the composer for tenor John Beard, Clayton’s voice carries equal parts drama and delicacy. As well as the music of Handel, the album features lively, lovingly performed selections from the mid 18th-century, including William Boyce’s serenata Solomon, John Christopher Smith’s opera The Fairies, and Thomas Arne’s opera Artaxerxes.

On the album’s first track, “Tune Your Hearts To Cheerful Strains” (from the second scene of Handel’s oratorio, Esther), the scoring features voice and oboe gently weaving their way in, around, and through one another in beads of polyphonic perambulation. Clayton’s timing, pushing sound here, pulling it back there, moving into blooming tenorial splendor before trickling watchfully away like a slow exhale, is artistry worth enjoying over several listens. Equally so the aria “As Steals the Morn”, taken from Handel’s pastoral ode L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (The Cheerful, the Thoughtful, and the Moderate Man), which is based on the poetry of John Milton. The graceful call and response of the instruments is echoed in the gentle if knowing exchange between vocalists, in this case Clayton and soprano Mary Bevan, their poetic, deeply sensitive vocal blending underlining the bittersweet truth of the text, with its tacit acknowledgement of the illusory nature of romance. The work is set within a wider contextual framework extolling the virtues of moderation, but Clayton and Bevan inject the right amount of wistful sadness the whispering kind, with Clayton a burnished bronze tonal partner to Bevan’s delicate glass. Theirs is a beautiful pairing, and one hopes for further collaborations in the not-too-distant future.

As well as early music, Clayton’s talents have found a home with twentieth century repertoire, and he’s been able to exercise both at the Komische Oper Berlin, a house he openly (as you’ll read) proclaims his affection for. In spring 2018 Clayton performed as Jupiter in Handel’s Semele, and later that same year, made his role debut as Candide in Leonard Bernstein’s work of the same name, with Barrie Kosky at the helm. Clayton returns to the house for its 2020-2021 season, as Jim Mahoney in Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (The Rise And Fall Of The City Of Mahagonny) by Kurt Weill, another role debut. Clayton has also appeared in Rameau’s Castor and Pollux at English National Opera (his performance was described by The Arts Desk as “astounding, his piercingly ornamented aria, “Séjour de l’éternelle paix”, one of the highlights of the evening”) as well as Miranda, a work based on the music of Purcell, at Opéra Comique, under the baton of Raphaël Pichon and helmed by Katie Mitchell. And, lest you wonder if he works only at opposite musical poles of old and new, consider that Clayton, who started out as a chorister at Worcester Cathedral, has also given numerous stage performances as David in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, both at the ROH, under the baton of Sir Antonio Pappano, and at Bayerische Staatsoper, with Kirill Petrenko. November 2018 saw the release of his album of Liszt songs, recorded with renowned pianist Julius Drake.

And yet, as mentioned earlier, Hamlet is still arguably what Clayton is best known for. The opera, by Brett Dean, with libretto (based on Shakespeare) by Matthew Jocelyn and presented at the 2017 Glyndebourne Festival, featured a stellar cast including Sarah Connolly (as Gertrude), Rod Gilfry (as Claudius), Barbara Hannigan (as Ophelia), Kim Begley (as Polonius), and Sir John Tomlinson (as the Ghost of Hamlet’s father). Clayton,who made his debut at the Festival in 2008 (as the title role in Albert Herring), gave us a Hamlet that was the veritable eye of the hurricane as well as a tornado of energy himself. There was no perceptible line between the worlds of vocalism and drama in the slightest; the performance, matching the opera as a whole, was a perfect fusion of the varying art forms opera encompasses. Dean’s hotly dramatic scoring and Jocelyn’s musically rhythmic libretto provided a whole new window into the world of the gloomy Danish Prince, one divorced from the arch world of hollow-eyed, sad-faced, skull-holding clichés, but sincerely connected to truly felt, deeply experienced aspects of human life: what it is to love, to lose, to grapple with notions of shifting identity and an unknowable present. The work carries extra poignancy in these times and remains a strong personal favorite.

In 2018 Clayton was the recipient of both the Royal Philharmonic Society Singer Award as well as the Whatsonstage Award for Outstanding Achievement in Opera. 2019 proved just as busy and inspiring, with, among many musical pursuits, including much time with the music of Berlioz – at Glyndebourne, as the lead in La damnation de Faust, and then as part of the oratorio L’enfance du Christ (The Childhood of Christ), presented first at the BBC Proms with conductor Maxime Pascal, and later at Teatro Alla Scala, with conductor John Eliot Gardner ). In September Clayton travelled to Bucharest to premiere a new song cycle by Mark-Anthony Turnage at the Enescu Festival before presenting it shortly thereafter in London, where the work was performed along with related pieces by Benjamin Britten, Oliver Knussen, and Michael Tippett; The Guardian’s Andrew Clements later wrote of the concert that Clayton’s voice “wrapped around all of (the compositions) like a glove, with perfect weight and range of colour and dynamics.” Clayton and Turnage are two of four Artists in Residence (the others being soprano Julia Bullock and composer Cassandra Miller) at this year’s edition of the Aldeburgh Festival, set to run June 12th to 28th. Founded in 1948 by composer Benjamin Britten, tenor Peter Pears, and librettist Eric Crozier and spread across various locales in Suffolk (with the converted brewery-turned-arts-complex Snape Maltings being its hub), Aldeburgh offers performances of everything from early music to contemporary sounds, and attracts a heady mix of audiences just as keen to take in the gorgeous landscape as to experience the wonders of the festival. Clayton is presenting two concerts which will feature the music of Britten Turnage, Ivy Priaulx Rainier, and Michael Berkeley (a world premiere, that) as well as perform as part in a performance of Britten’s War Requiem with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, led by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla. It all remains to be seen, of course. As pianist Stephen Hough wrote in The Guardian, “it’s impossible at this point to say where this will end” – it is equally impossible at this point to say where things will begin, too.

I’ve presented this interview in two parts, as you’ll see, which act as a sort of yin and yang to one another for perspectives and insights into an oft mentioned, rarely-explored world that makes up opera, that of the rehearsal. As you’ll see, Clayton speaks eloquently about its various moving parts (particularly, in this case, linguistically-related) and the weeks of preparation that go into a new production, the fruits of which, like so many in the oprea world right now, will not be enjoyed by any. It’s tempting to write such effort off, to say it was in vain, but my feeling is that the best artists, of which Clayton certainly is, have taken their bitter disappointment and turned in inside-out, finding new energy for forging creative new paths; they are roads which, however unexpected, are yielding their own sort of special fruit in some surprising ways. Clayton’s mix of playfulness, curiosity, and earthiness seem to be propelling him along a route showcasing his innate individualism and artistry. I am looking forward to the results, to say nothing of the cross stitch projects promised herewith.

Photo © Sim Canetty-Clarke

Before Jenufa‘s Cancellation

How are rehearsals for Jenufa going?

I’d not done any Czech opera at all and this has completely opened my eyes to the whole music I knew was there. I’d heard some things and seen the opera before at the Coliseum in that famous production in English, but the richness of the score and the music, it’s so emotionally present, there’s no artifice – hopefully it’ll be the same live.

It’s written phonetically, an approximation to match the inflections of the language…

Exactly.

… so how are you finding learning not only Czech, but, as a singer, matching it to the sounds in score?

Something our director Claus Guth said on our first day, with the rehearsal that afternoon, is that this something we have to create, with our own stage language, to deal with the repetition of text in a short space of time. It’s not a Baroque opera where you have extended passages of five or six words stretched out; you have very important information delivered rapid-fire. (Conductor) Vladimir Jurowski said, “you have to remember this is how, coming from that region, people would talk to one another, you bark . I’ve been in places in Eastern Europe” – and he’s speaking as a polyglot who rattled through seven languages in rehearsal – “and when you listen to them, it’s like they’re shouting at each other, but they’re not; they’re communicating in a staccato, loud, repetitive manner, so just embrace it as part of normal day life, because the piece is about routine and everyday life, and the threat from the outside to that.”

And the character is tough as well. Opera has lots of characters with chips on shoulders…

Yes indeed.

… but Laca has one of the biggest and chippiest chips.

Completely, and he cannot stop it. He hates Steva. We’ve rehearsed the scene where the infamous cut happens to Jenufa’s cheek, which is the beginning of the end of the story and we have talked about it: does he mean it? Is it intentional? In his very first scene, from the very start, he’s raging at people, and he has a furious temper, which is something else we talked about, that this was Janacek’s character, he could fly off the handle at any time and took badly to things, and he was tempestuous in relationships. This is something I try and embrace but not let it affect me vocally and move into shouting, because that’s not nice to listen to!

It’s not vocally healthy either.

No!

You also did Candide in Berlin, which is totally different. Finding your way through extremely complex scores when it comes to new roles – what’s that like?

For Candide, it was a chance to work with Barrie Kosky again, who I get on really well with – I think his approach to directing and to life is a pretty solid one, and I agree with a lot of what he says. It was also a chance to work at the Komische Oper again; I’ve done quite a few shows there now, it’s a positive space to work in, even though it’s a busy house, but it’s also the chance to do something different. He said, “we’re going to do it in German” and I thought, right, thanks a lot! I only speak a little German but not near enough, so learning dialogue was a challenge, but I also thought: it’s a chance to do something a bit more theatrical. That was certainly what I enjoyed. The creative input I had on it was the most I’ve ever had, because we had a completely blank stage, and Barrie would go, “okay, we need to get from this locale to that locale in the next page-and-a-half of music; we have no set, so what do we do?” We had fun with that. I could say, “Well why don’t we kick a globe around, or do a silly number with Monty Python-style soldiers?” The challenge, and the great thing with him, is always, this creative side of things.

And Barrie is so open to artistic collaboration.

He is! I‘ve often said the best directors – and he is one of them – make you think you’ve come up with a great idea, which is probably what they wanted all along, but they make it feel like it’s a collaboration, that you are not just a cog in a machine. Again, like Claus was saying in rehearsal he had some plans for certain scenes but the natural circumstances means the scene will go in a completely different direction – and he loves that. It’s about embracing that flexibility. If you just go in there and think of yourself like a moving statue, it makes for a very long six weeks.

Some performers enjoy the predictable – it’s comfortable and they say they can concentrate on their voice more that way – but for you that doesn’t feel like the case; it feels like comfort is the antithesis of who you are as an artist.

Yes, and the most fun I have is in rehearsal room. The pressure is on when you do a show, in that you want the audience to be happy, you’re trying to be faithful to the score and remember your words and blocking and all else, but actually being in a rehearsal room for five or six weeks with brilliant colleagues and creative minds makes it interesting, and for me that’s the part of the job I enjoy. When people say, “you must be so lucky to do what you love” that’s the bit I think of, because if I didn’t do that, I’d be trudging out the same couple of roles and it would be boring as hell. How do you bring something different each time doing that? You fall into one production or role, like “this is my Ferando, this is my… whatever”, which is so less interesting.

But it takes a lot of confidence to go into those rehearsal for the length of time you do, with the people you do, and say, openly, “I have these ideas and I want to try them.”

I guess, but it doesn’t always feel so, though that’s also why, for me, whenever I’m speaking to casting people or my agent about future projects, my first question is always, “who’s the director?” Because it’s massively important – the conductor is always the second question, but if I don’t feel the director is going to trust me or if I can’t trust them, then I won’t have the confidence to put those ideas out there and try some things. Like, this role, it’s about offering things when i can and not holding up rehearsal when it’s not my turn. That’s part of being a team. That’s part of working collaboratively.

Humility is so vital, especially in the world of classical music, where egos can get out of control so quickly.

Exactly! It’s something I’ve not had to deal with a lot, but (that egotism) is so alien to me, I think there’s less of it maybe than there used to be, or maybe the level at which I work, but it can be difficult.

Your Hamlet was very ego-free, and very beautiful.

It was such a special opera, wasn’t it?

I spoke to Matthew Jocelyn when he directed Hamlet in Köln in November 2019, and he was also clear about the role of collaboration in its genesis.

Yes absolutely, I can’t imagine a more perfect storm. The way Matthew and Brett got on, even if they didn’t share ideas, was always dealt with in a creative and good way, and it was the same with (director) Neil Armfield and Vladimir Jurowski, and with Glyndebourne as a company as well. I can’t imagine that piece working anywhere else. There was an incredible amount of people who gave above and beyond what you’d expect; it was extraordinary, and was given without a question. I don’t know what it was, but every department was being collaborative, from Matthew and Brett’s first jotting down which scenes they wanted to include, to the first night. Everybody was giving everything.

That generosity of spirit bleeds into the concert work I’ve seen you do, your 2018 performance of Spring Symphony with Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra, for instance…

If I didn’t keep a mix of things I’d go even more insane than I am!

Is that why you do it? Staving off restlessness?

Completely. I can’t imagine that part shutting off. If I didn’t do concerts or recitals, I’d be shutting off two-thirds of what can be done with this amazing, weird world we live in. I think of the music I’d be depriving myself of, so it’s also a selfish thing, with recitals but also with concert work. You get to be more involved in how you present things, you have a more immediate connection to the orchestra or pianist or chamber group, which you don’t get in opera because you are separated by the floor, so it’s slightly more engaging for me.

You also bring an operatic approach to those formats, though, as with the Britten, you live right inside those words.

You have to with a lot of Britten – if you don’t engage, you’re lost. It’s so dramatic, and he writes so well for the stage because he has a natural sense of drama throughout his writing, and you know, if you are just trotting it out without really going for it, it doesn’t make for a good experience for the audience

But you can’t do that in recitals; artists say it’s like standing there naked, although Thomas Hampson said he thinks all singers should do them.

It’s true, you explore so many different colors than you would in opera. It’s hard, hard work to keep that concentration that long and stamina-wise. In terms of preparations you put in for the output, you might do each recital once, so it’s weeks, hours, months of work to inhabit each song and try to say something fresh with it since the three-hundred-or-so odd years since it was written, but that’s what makes it fun.

I would imagine you come into Jenufa rehearsals, having done your recital at Wigmore not long before, for instance, with a new awareness of what you can do with your voice.

Absolutely, yes, and it makes you more interesting for directors and conductors, because if you can offer these interesting colors they’re like oh cool!” Just the other day, I was rehearsing and Vlad said to me, “Don’t come off the voice there, it doesn’t work” – so (responsive versatility) is an option I can offer, it’s not just full-frontal sound, or one color, and that’s again, about confidence. The more (varied) stuff you do, the more options you can present.

And you are Artist in Residence at Aldeburgh this year too.

It’ll be great – I love that place. When I was in my first year of music college (at St. John’s College and later the Royal Academy of Music) I did Albert Herring there as part of a student program, and it was seven weeks in October living in Aldeburgh, learning about the region and all the weird people from that place. It couldn’t have been a better introduction to the place and what it means to not only British music but internationally as well. The residendency, well I’m so chuffed, and especially happy with the other people doing it too.

Their ten-quid-tickets-for-newcomers scheme also fights the idea that opera is elite.

It’s crap, that view – but you feel like you’re speaking to the wind sometimes. I was in a taxi going to the Barbican doing Elijah a few weeks ago and the driver said, “oh, big place is it, that hall?” I said, fairly big, he said, “like 300?” I said, no it’s about 2000 or something, he said, “oh gosh!” I said, you should give it a go someday. He said, “I can’t, it’s 200 quid a ticket”, and I said, no, it’s five quid, and you can see lots of culture all over for that price, for any booking. I mean, it’s infuriating – I took my sister and kids to see a football match recently and it cost me the best part of two grand. I mean, talk about classical being “elite”!

Baroque is a good introduction for newcomers I find, it’s musically generous and its structures are discernible. You’ve done a good bit of that music too.

If I’m free, I say yes to doing it. That music is really cool to do, things like Rameau, which I really didn’t know about, and Castor and Pollux, which blew my mind, and as you say, the music is so beautiful, it’s not too strange or contemporary, so people can engage with it easily.

And it’s a good massage vocally.

Yes, not crazy Brett Dean vocal Olympics!

Photo © Sim Canetty-Clarke

After Jenufa‘s Cancellation

Sorry for the delay, I was just doing an online task with my family, it wasn’t working and I was swearing and throwing things at the computer. How are you?

Trying to figure things out.

It’s such a change, isn’t it…

I teach as well and had my first Zoom session with my students recently.

How did it go?

Nobody wanted to hang up at the end – they were so happy to see each other. I wrote about that moment recently.

My youngest niece had the same thing this morning – a mum arranged a big Zoom class phone call and my sister said exactly the same thing: they just loved seeing each other.

I think everyone misses that community.

Yes, and especially given how close we got to opening Jenufa; tonight (March 24, 2020) would’ve been the opening.

I’m so sorry.

Well, thanks, but certain people are in much worse situations, so it’s not the most important thing. It is a shame, though; everyone had worked so hard and put so much into a show that was going to be so good. I was chatting last night with Asmik Grigorian (who would have sung the title role), and she was saying how opera houses plan so far ahead and it’s difficult to know how they’ll cope with these loss of projects, whether they’ll put them on in five years’ time or move things back a year, but you do that and then you’re messing with people’s diaries in a big way. Fingers crossed people will get to see what we worked on anyway, at some point.

Some of those diaries are now big question marks.

Absolutely. I’d’ written off Jenufa until Easter, and then after that I was supposed to go to London – Wigmore Hall – and then New York, then Faust in Madrid and Hamlet in Amsterdam. I’ve written all of them off, because I can’t see things being back to normal the beginning of May, or even the end of May, when Hamlet is supposed to happen. And I’ve got the opera festival… I’m hoping it’ll be able to go ahead, but the brain says it won’t happen either, so suddenly my next job isn’t until August. We’ll see if things have calmed down by then.

It’s so tough being freelance, there’s this whole ecosystem of singers, conductors, musicians, writers, and others that audiences usually just don’t see.

My sister is a baker, she has her own business; she’s self-employed. And obviously all the weddings have been cancelled, and birthday parties, and all the related stuff, like cakes, musicians, planners, all these people – all cancelled. So yes, it isn’t just singers in opera but people like yourself, the writers too – we’re all in the same boat. We are together under the same banner of freelance and self-employed, but at the same time, at least in this country, we’ve been abandoned under that same banner by the government.

It was notable how loud freelancers were through Brexit about the implications to its various ecosystems.

I don’t know whether it’s because us freelancers spend a lot of time working on our own and are not part of a bigger company, but it’s why Brexit felt so silly, because to become more isolated at a time when the world becomes less so, just doesn’t seem to make any sense. You’ve got the rest of Europe, although it’s closing its borders, it’s maintaining as much community and spirit as it can, whereas little Brexit Britain is just sort of shutting down.

And in the current circumstances, literally doing so rather late. The scenes of the crowded parks this past weekend were…

It was absolutely insane.

So how are you keeping your vocals humming along?

I have a couple of projects – I did a Mozart Requiem of sorts, with Joelle Harvey and Sascha Cook, the American mezzo. She was in Texas, Joelle was in Washington I think it was, and I was in Lewes, and we did this arrangement where I did the soprano part, and Joelle sung tenor, which was pretty special. I’m doing something with the French cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton as well – I sent her the Canadian folk song “She’s Like The Swallow” recently. We’ll record some Purcell later today. She’s going to try to put her cello to my singing. So, little things like that going on. Otherwise, we’ll see what happens really. I’ve got my laptop and a microphone and a little keyboard with me, so hopefully I’ll do something, maybe a bit of teaching and singing as well to keep the pipes going.

A lot of people are turning to teaching now.

I wouldn’t do anything seriously, I just think it’s nice to be able to use what is the day job in other ways. A friend put on Facebook yesterday, “is anyone else finding the silence deafening?” I think that’s apropos at the moment. We’re so used to hearing music all day, to having it be part of our regular lives, six or seven hours (or more) a day, in rehearsals and at concerts, that feeling of making music together and hearing music live – it’s just not the same at the moment .

Performing at the 2019 George Enescu Festival with the Britten Sinfonia and conductor Andrew Gourlay. Photo: Catalina Filip

The performative aspect too – there’s no live audience. It’s nice to feel somebody is out there in a tangible way.

That’s the thing, it’s only times like this you realize what a two-way process it is. It’s so easy to think, without experiences like this, that we’re on stage, people listen to us, and that’s it. And it’s not like that at all. The atmosphere is only created by the audience. When things were heading south at the opera house and we weren’t sure what would happen, there was talk of trying to livestream a performance without any audience in Covent Garden, and we were considering that, and thinking, like, how would that work? The energy wouldn’t be at all the same. It’s completely intangible, but it’s a vital part of the process, of what we do.

Having that energetic feedback…

Absolutely, the buzz in the room. People stop talking when the house when lights go down – it creates adrenaline for us, it creates a sense of anticipation, in us, and with the audience, of “what will we see, what are we going to hear, are we going to enjoy it and engage with it and get out of the 9 to 5 routine?” And it’s the same for us: will we be able to get out of our daily commute when we step onstage and see smiling faces (or not)? All of those little interactions that we took for granted – I certainly did – well, we don’t have the option anymore.

And now you have to try to adjust yourself to a different reality, like the Zoom meetings, and there is that weird community sense being together and alone at once.

Exactly, because we’re all stuck in the same boat. We have to accept things like Zoom, Skype, Facetime are the only ways we’ll cope, otherwise we’ll all go mad. It’s very well hearing one another’s voices but seeing – the things we get from humans, from facial tics – that reaction is another level, and without it we’ll start to go insane. I’ve got a Zoom pub date lined up later this week with a couple musician friends, we’re going to sit and have a beer together and chat, just as a way of keeping in touch.

It makes things feel semi-normal too.

Exactly, because you know, you put yourself in their spaces, their homes, you see their living room, and given that we’re all stuck in our own environments at the moment, it’s very important to have as much escapism as possible.

We’re getting peeks into homes, and there’s a weird sort of familiarity with that because everyone’s in the same boat.

I find it interesting! My sister was saying at lunchtime, remarking how interesting it is seeing journalists’ living rooms, because they’re broadcasting from there now, it’s a peek behind the curtain, which is really quite nice.

And everyone has the same anxious expression…

… because we don’t know where this is going.

Hopefully things will be clear by the time you start work on Rise And Fall Of The City Of Mahagonny at Komische Oper Berlin next season.

I love Barrie Kosky, and I’ve not sung Mahagonny before, so I’m looking forward, though it’s a weird piece. I said to Barrie when he first offered it to me, that scene whilst Jimmy’s waiting, the night before he dies, when he’s praying for the sun not to come up, it’s like a (Peter) Grimes monologue, it’s like Billy Budd through the porthole, this really, really operatic bit of introspection.

It’s also kind of like Madame Butterfly turned inside out…

Quite!

I wonder if Weill was aware of that when he wrote it.

I hadn’t made that connection at all but you’re absolutely right! It’ll be fascinating to see what Barrie does with it.

You have lots of time to prepare now.

That, and all the other projects next year. We’ll see what happens, but it’ll be great to focus on those. That’s what I’m having to do at the moment: focus on next year and hope what we live with now goes past us. I’m still going to prep for concerts that were set to happen, even if they don’t, in New York and at Wigmore Hall. I put a lot of time into the programming, especially at Wigmore this season, and off the back of those programs I’m hoping to do some recordings, and later maybe tour the same programs, or an amalgam of them, but certainly it makes sense to keep doing it, and to satisfy the creative part of my brain. I have to be doing something like that. If I don’t see any printed music, I’ll go crazy; it’s been my life since the age of eight, so I need it. I don’t know what to do with my days if they don’t have music in them. I’ve also taken up cross stitch, but I can only allow myself to buy cross stitch with swear words in it, so that’s my next project.

Will you be sharing the fruits of these labours?

Absolutely.