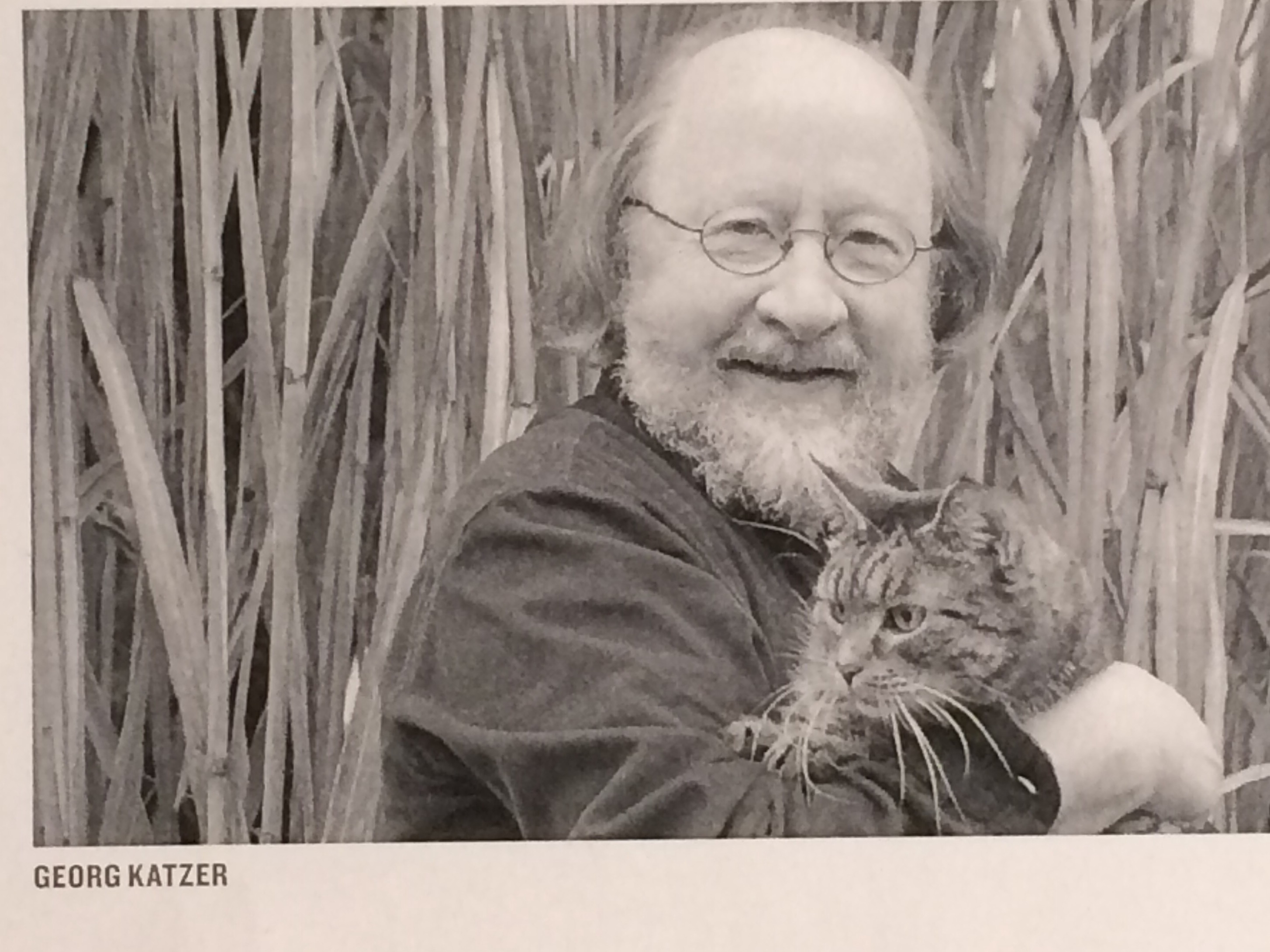

Photo: Paul Scala

If there’s one quality that can be applied to Saimir Pirgu, it’s bravery, though perhaps “ballsy” is a better word.

Having left his native Albania as an ambitious teenager intent on a singing career, he graduated in singing at the Conservatory Claudio Monteverdi in Bolzano, and was singled out by conductor Claudio Abbado at the tender age of 22 to perform the role of Ferrando in Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Three years earlier, however, he sang for another famous opera figure: Luciano Pavarotti. And what an introduction it was. In the midst of his studies at the conservatory, the great Italian tenor, who was visiting the area in the early 2000s, had requested to hear a few of the school’s students. Pirgu launched into “Uno furtiva lagrima” from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, a well-known work arguably made even more famous by Pavarotti’s famed performances of it. (What’s more, Pavarotti had named Nemorino (Donizetti’s famous dolt of the opera) as his favorite opera role of all time.) In a 2017 interview, Pirgu recalls Pavarotti aking with wonder at the end of his performance, “Who taught you to sing like that? Do you know that you sing very well?” It would mark the beginning of what has become a very busy career.

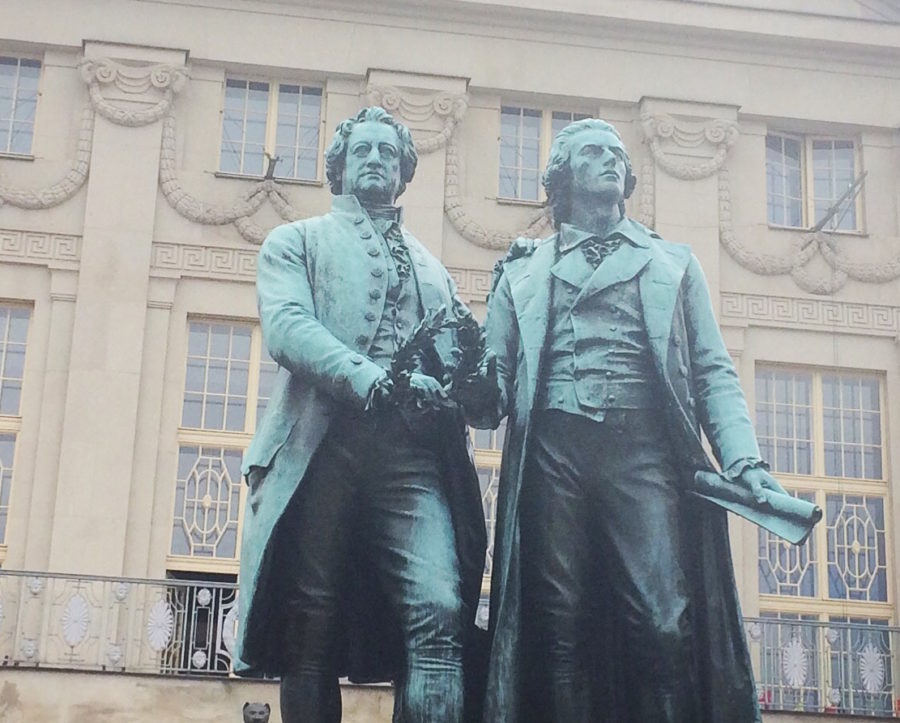

The tale underlines Pirgu’s no-nonsense personality and ambitious approach. With a full calendar and appearances at such renowned houses as the Wiener Staatsoper, Bayerische Staatsoper, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Paris, Opernhaus Zürich, and Teatro Regio di Parma, Pirgu has also performed in some unique locales, including, this past summer, with the Greek National Opera at the ancient site of Odeon of Herodes Atticus at the Acropolis. Listen to Pirgu singing and you may be forgiven for thinking you’ve turned on something from another era; his flexible, mellifluous sound conjures up ghosts of opera yesteryear, and is beautifully suited to the lyrical Italian and French repertoire he focuses on. That doesn’t mean he’s a fossil, embraces intransigent historicism, or only appears in old-style productions; quite the opposite. Pirgu has appeared in some very modern productions (as you will see) and has some strong thoughts about the role of the director and singer relationship. There’s no denying his 2015 album, Il Mio Canto (Opus Arte), recorded with powerhouse conductor Speranza Scappucci and the Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, is a wonderfully vivid display of the sort of old-school vocal fireworks and deep lyricism at which he excels; comparisons have, therefore, predictably been made between he and historic tenors like Giuseppe Di Stefano, but, as you’ll read, he takes it all in stride, preferring to focus on the task at hand.

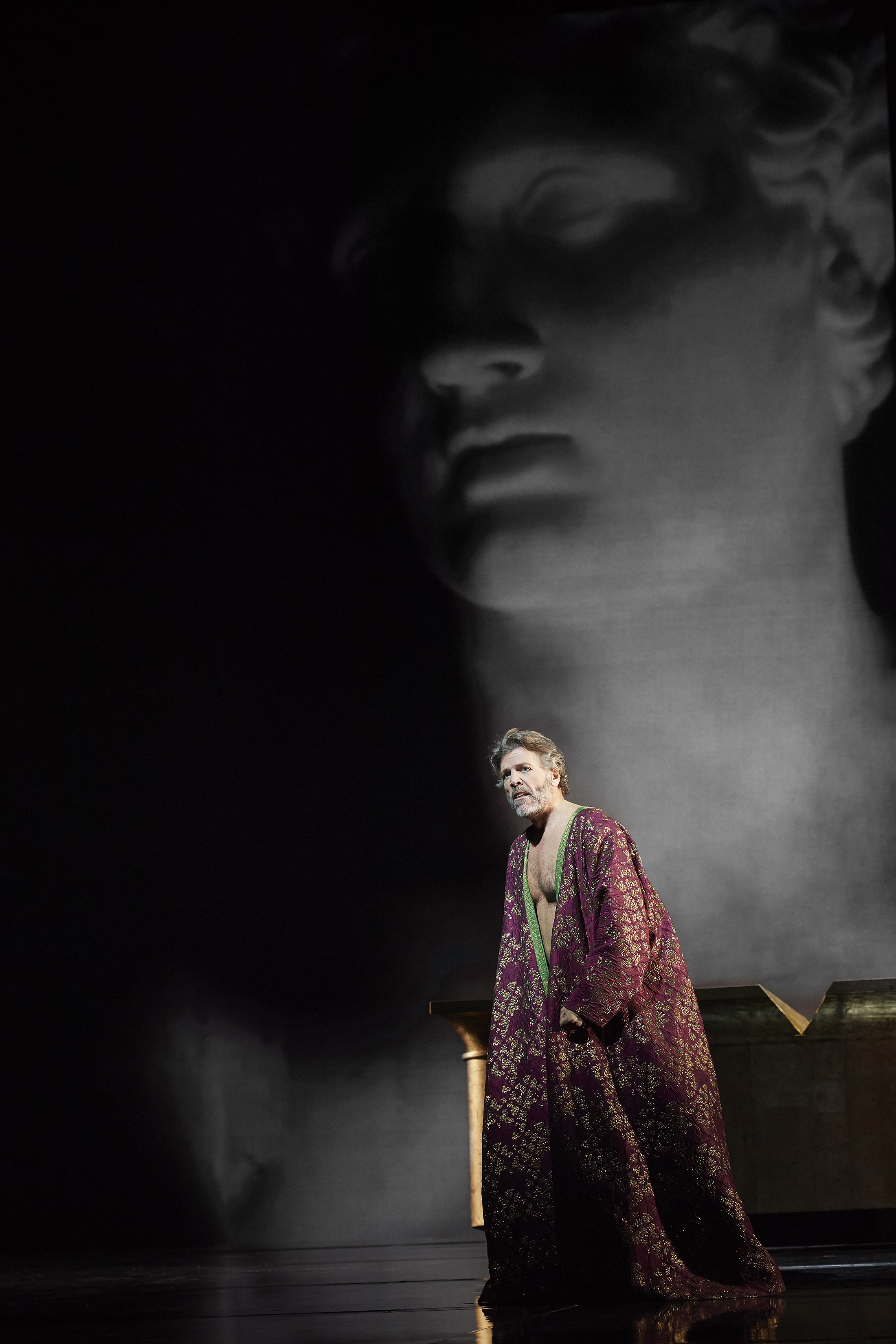

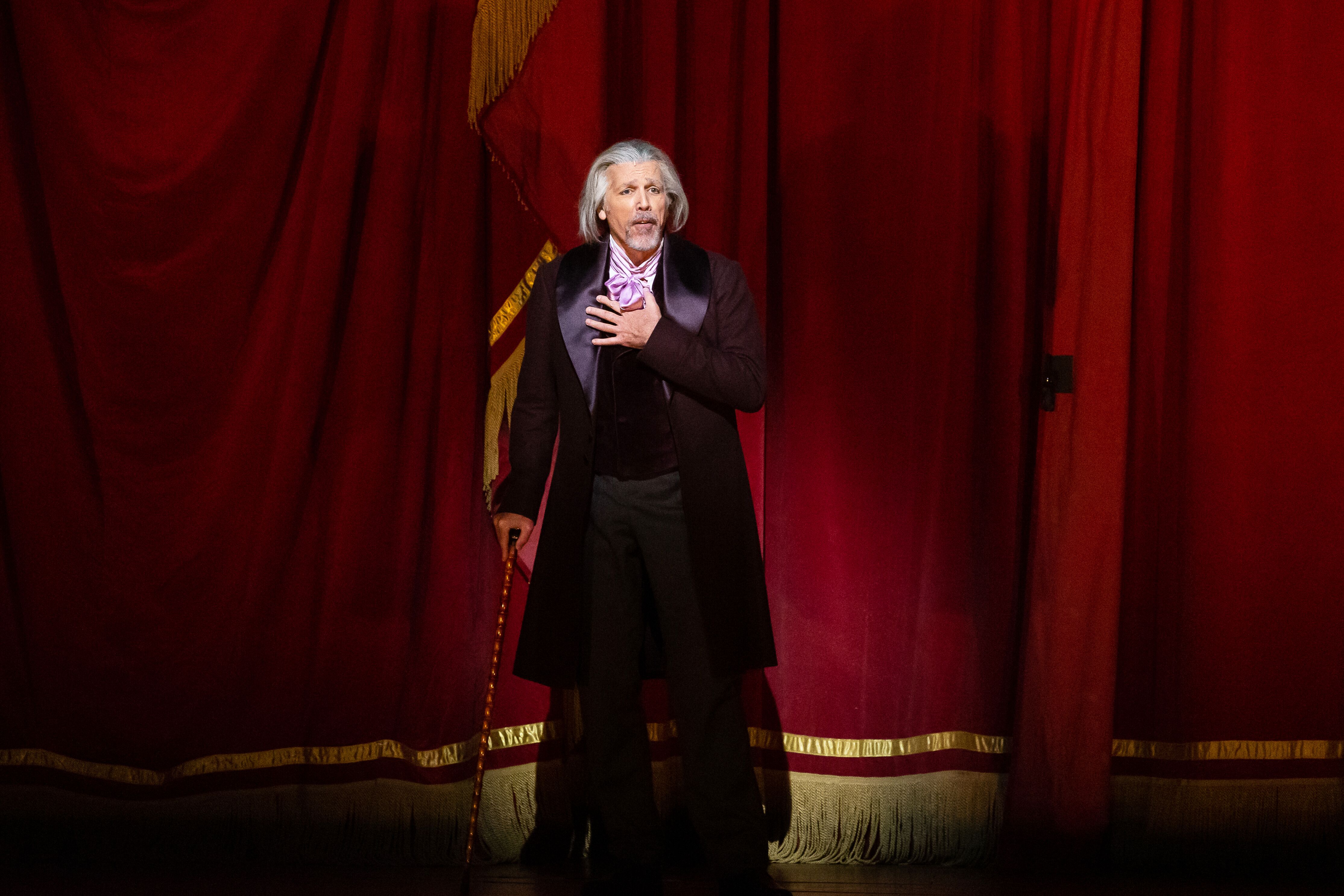

As Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, Teatro di San Carlo (Naples), 2019. Photo: Luciano Romano

Earlier this year he appeared at Royal Opera House Covent Garden as Edgardo in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, a role he previously performed at Teatro di San Carlo (Naples) and Staatsoper Hamburg. Over the years, he’s tackled a number of chewy Verdi tenor roles as well, including Macduff in Macbeth (at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona in 2016), Gabriel Adorno in Simon Boccanegra (Naples, 2017), and Riccardo in Un ballo in maschera (Parma, 2019). This is particularly intriguing, since Pirgu’s career has been so firmly centered around what might be considered the “grounding” roles for tenor repertoire: Puccini’s Pinkerton (from Madame Butterfly), The Duke of Mantua (Rigoletto), Verdi’s Alfredo Germont (from La traviata) and Donizetti’s Nemorino (from L’elisir d’amore). I’m keen to see (and hear) him tackle meatier sonic things; I want to hear his Riccardo, Macduff, Adorno live, as well as his Don Alvaro in La forza del destino, because I think Pirgu’s vocally come to a place where he not only can do it, but he should. With a dashing, old-school stage presence and remarkable vocal heft and flexibility, Pirgu is a tenor to watch, follow, carefully listen to.

Despite his bold, ballsy approach, Pirgu has been careful in choosing his roles. His move into French opera has been watchful, with past appearances in Cyrano de Bergerac, Roméo et Juliette and Werther; he closes out 2019 with a role debut as Gounod’s Faust with Opera Australia, a role he’ll be performing again in Zürich in May. His next performance is in La bohème at L.A. Opera on Saturday (September 14th) – he sings the main role of Rodolfo in the Komische Oper Berlin production – before singing Don José in Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. Next year he’ll be tackling his very first Lensky in Teatro dell’Opera di Roma production of Eugene Onegin under the baton of James Conlon, with whom he has worked many times, and with whom he is currently working in Los Angeles. All of this bodes well for a tenor whose voice is exploring intriguing and beautiful possibilities.

We recently spoke about the challenges and joys of new and old productions, his thoughts on the pressures singers face within the digital realm, and why having the right conductor makes all the difference.

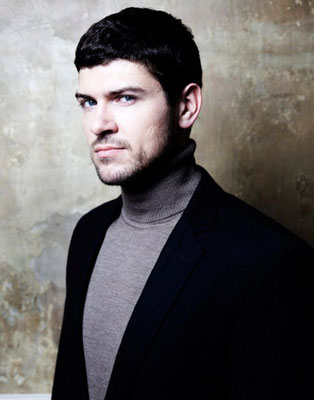

In Idomeneo (Styriarte Festival Graz 2008)

You’ve worked with a variety of directors, some of whom take modern approaches, others the so-called “traditional” approach. Does either approach affect you creatively? I saw the Damiano Michieletto production of Rigoletto in Amsterdam and thought it really captured what that opera is all about.

It was very intelligent, that production. I agree that people say, “Oh but it’s not the real story!” or “It’s not the way it usually is!” but… a new director who wants to say something, what he can do? He just has to experiment like this in an intelligent way, to suggest that the opera is not just one thing – it can be another idea, it can be another thought of what the story can be. I don’t like to say that I like old-fashioned or Regie or whatever, for me it’s just a case of asking, is it intelligent or not? Is it beautiful or not? And the answers depend on if the director is prepared to show something to the public. I’ve worked with both styles. When I did Don Giovanni with Zeffirelli in Verona it was this massive wonderful production with original costumes it was amazing; the colors of that production and the costumes, it put you in this old-world epoque.

But this Rigoletto from Michieletto… and the one I did in Zurich with Tatjana Gürbaca: she just had a table and we went up and down and around it. There was just one big table in the middle. It was difficult to do. It showed me the directors have ideas. You can transmit it to the singer and we can do our best to give the best to the public, but if the idea doesn’t come through, then it doesn’t matter if it’s old-fashioned or if it’s a new production – it’s always the same: it doesn’t have success. People today are not stupid; they see television, musicals, online. And in the opera world, if the production involves everybody in the overall idea, of course they have a wonderful experience. And that’s the case with Barrie Kosky’s production of La bohème – it’s between people, it’s not just showing costumes or stage design.

It underlines the human drama.

Yes.

You mentioned the competition with other media, and I wonder about digital influence. Some singers have told me the livestreams and HD broadcasts add another layer of pressure; one singer said he felt he was competing with Hollywood.

Today it’s important to look good. It’s our society. It’s not anymore about us, it’s about looking good, dressing well, so people … it’s a bit superficial – may I say that it is, yes. Sometimes a cover of a magazine is more important than a live performance, so you’re spending hours and hours and months in rehearsal, but with the cover on a magazine it doesn’t matter, it’s more important to have that image, than the real world. In the opera world, that doesn’t always work because we have direct feedback from the public; if you sing well, they applaud and if not, they don’t. So we have to be careful. The image has become very important and it’s why a lot of opera stars publishing pictures of what they drink and eat and how they dress, because they know the public now has changed, and is more like, “Okay, let’s see what the soprano is wearing at the party.” I’m sorry, for me it’s a bit superficial, but I know it is also the reality today.

In Werther, New National Theatre, Tokyo, 2019.

You mentioned audiences applauding or not, but they vary greatly, being wildly different between North America, Germany, Australia and Greece, for instance. Every audience you perform for will be different based on cultural awareness, exposure, expectations. What’s that like to deal with as an artist?

It’s not easy. In Italy and Spain they want to hear the voice first. If you’re a good actor, okay, it’s a plus, if you have stage presence, that’s okay too, but they want to hear voices, they want to hear: can you sing or not? And other parts of the world they’re more focused on acting and performance – it isn’t solely about singing. So it’s difficult to know what the public wants. I’m more concerned to sing in Italy, for example, because I know they will judge how I sing. Of course if you act very well it’s a plus in your interpretation but for them it’s important how you sing, the sound of your legato. I’m not saying for London or Amsterdam it’s not important, but they want to see a show; they see the whole performance differently. They go to the theatre to see the opera; they don’t go to see Pavarotti or Callas only. Whereas Italians will go for a specific singer. They want to enjoy that. So it’s different. The culture in Japan and other countries in Asia, they’re very nice and very silent, and really listening. You don’t understand if they like it at all until the very end when they do huge applause; they don’t want to disturb your performance.

Musician friends of mine who’s toured there have noted that the quality of listening from audiences in Japan and Korea is incredibly high; that can be both great and nerve-racking.

Yes, it is. And the lines after the concerts are huge! You may have sung a three-hour opera but people are willing to wait an hour or two for an autograph or at a CD signing. It’s a different culture. You have to be prepared.

That preparedness has shown itself in your careful choice of repertoire over the past while. What has it been like to explore, and where do you want to go with French and Italian work?

I’m enjoying my lyric repertoire right now, i have the feeling the voice is stable in that repertoire and every time I do it I’m getting better and better. It gets good feedback too. I’d like to do both French and Italian repertoire for as long as possible – first, because i like it, and second, because it’s the healthy thing to do. You keep going when you have wonderful results. So why not? I will not move to other big repertoire – I’ve always been careful about moving around with rep – but I’ll keep doing it too. It’s the only way I know, and it’s what gives me success, so why change?

Within that repertoire, your version of “È la solita storia del pastore” at Wigmore Hall was really special. Would you do more?

I think I will be doing more this year. It depends how you book yourself and if you have a new program and … it depends. It’s time now to do a series of concerts, I am thinking that, it’s just a question of timing. It takes all of time and it’s a lot of stress for a singer to do a recital series around the world. You sing a lot of arias and you get tired very easily.

But I would imagine there’s something satisfying about it artistically that is different than being in an opera.

Yes, it’s a different mentality of singing. You need to have stamina to last through all these arias! You sing more than ten or twelve of them, not including encores. You have to be prepared, and you need a lot of stamina. It depends on the repertoire of course – between lieder and arias, it’s a different scale entirely.

And sometimes that scale involves comparisons. There have been comparisons between your voice and Di Stefano, for instance.

It’s very human – when (Tito) Schipa was singing people would say, “Oh, Del Monaco is better, or Corelli.” It’s human to compare. But the thing is, if you are god in our business, there’s a reason you’re working. Nobody gives you anything for nothing in this business, especially the public.

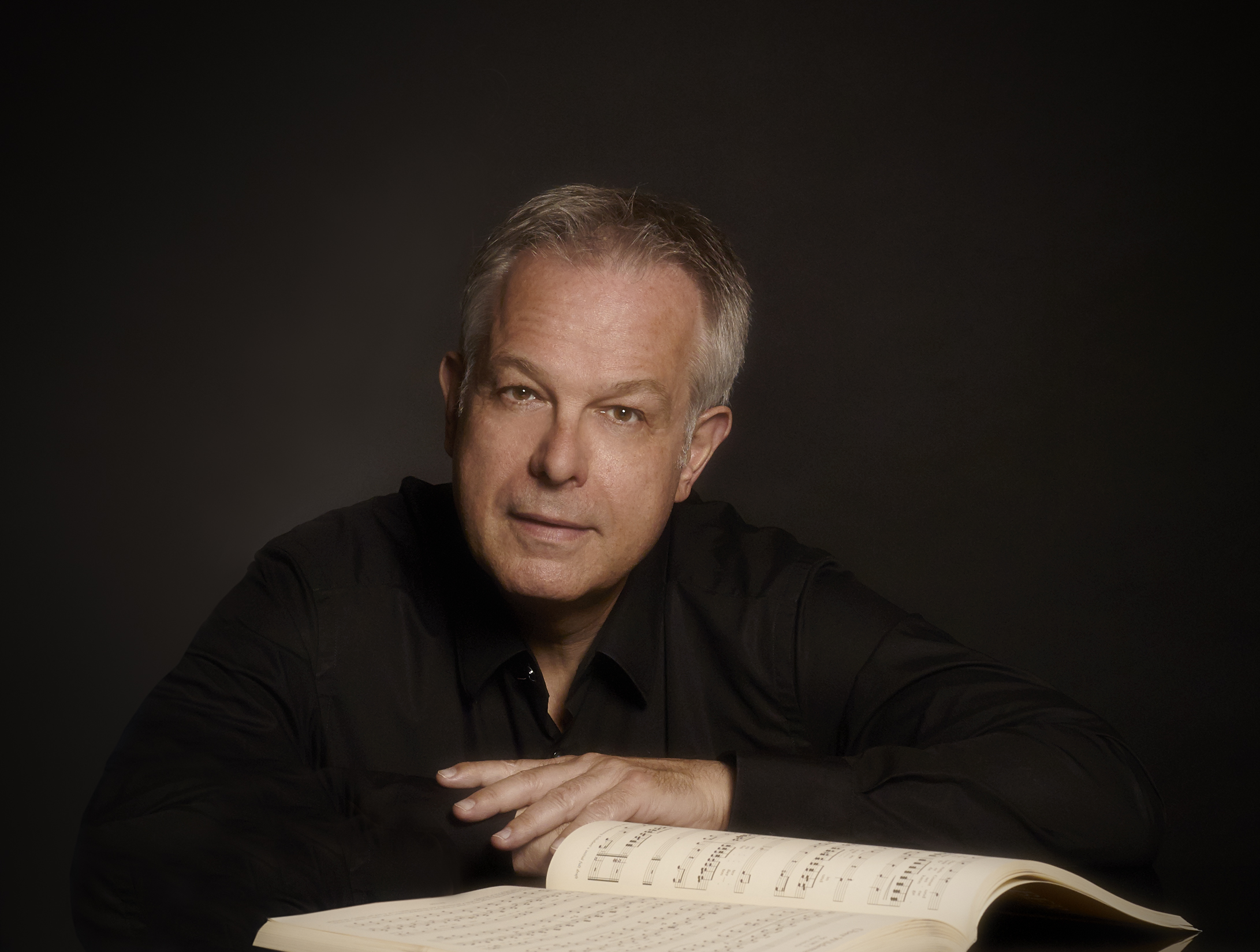

With conductor James Conlon.

Chemistry powers so much in the industry too. What kind of a difference does it make to have that quality with a conductor?

I’ve worked a Abbado, Muti, Harnoncourt, all of whom are completely different, but because I was a violinist before, it made it much easier to understand what they wanted. The conductors can treat the singers sometimes like an orchestra, not all the way, and not all of them have the knowledge of the singing, they read the score and say, “Okay, you have to sing what’s in the score,” and then you have some conductors who aren’t listening to the singers, and a lot of conductors who do listen to the singers, down to the last second. So it depends who you have in front of you, and it depends of course on how good those conductors are, but all the legendary conductors have to spend a lot of time studying singing, piano, violin, orchestration — they’re full with knowledge, so it’s odd if they come to singers unprepared. I’ve been blessed to work with so many great ones, and I’ve learned a lot about music. The most important thing is to be patient, and to listen, not to say something, because always you will learn something with them. Being an artist means there’s a lot of energy inside us, and you have to deal with that, it’s part of your business, but don’t forget that you’re a human being; that helps a lot in terms of other relationships in the theatre.