Throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere, the month of September heralds the idea of return: to schools and universities; to work projects; to extracurricular events and some form of cultural life in locales where summer festivals are scant if even extant. There is a hunger for routine, perhaps now more than ever, given the added impetus that the notion of “return” carries with it an end to the disruption wrought by years of pandemic. The urgency toward a “return to normal”, however one defines it, feels more tenuous than ever, given a tightening of budgets, of strikes, of continued sacrifice for some, of a winter that threatens cold and expense. Amidst all of this: whither music? Is it now firmly slotted as an extra? As temperatures drop and bills rise, priorities, especially for those on limited incomes, would seem to become plain. How, then, ought live classical culture to respond? How should it be encountered, engaged with, and supported?

Perhaps there is an answer in simple things – things like singing, and most especially singing with others. If the notion of ‘return’ engenders a thirst for community, what better way to slake it? Singing may be off the plate for most, but it need not be; there is no reason to feel daunted by any perceived lack of talent. Choral life in many parts of Europe and the UK is active, evidenced not only in a huge variety of live offerings but in audience response; attending performances of various Passions, it was lovely to note the extent to which respective audiences knew the words of various sections (and sang or hummed along, or mouthed the texts). There are many active choral communities across North America as well (Canada’s Nathaniel Dett Chorale is but one example), some secular, some not. Choral singing is, as practitioners might say, made up of far more than the annual Xmas ritual of Handel’s Messiah. The act of singing together within a confined space was one of the first things unfortunately lost in the pandemic lockdowns of early 2020; it was also one of the things fought hardest over in some places, with certain groups utilizing distancing techniques to try and continue their activities. Togetherness matters; making sounds together, certainly matters, as much an individual as a collective good.

The Merton College Choir is embarking on an American tour next week, one that seems as much about showcasing the talents of its members as serving to remind audiences of the centrality of communal cultural experience. The tour is a good reminder that singing need not be as formal as what the talented troupe present, but can be an act of recognition, of support, of active imagination and empathy. Made up of a rotating group of 30 members taken from Oxford University’s student body (via annual auditions), the choir (who has its own Youtube channel) is dedicated mainly to liturgical works, but also has (as their upcoming tour attests) a history of commissioning and presenting the work of living composers. Merton’s Choral Foundation was established in 2008, and since then, has acquired an international reputation for stellar performances and recordings. Awarded Best Choral Album at the 2020 BBC Music Magazine Awards for their 2019 recording of The Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ (Delphian) by Bermuda-born composer Gabriel Jackson (b. 1962) (a work Gramophone writer Alexandra Coghlan hailed for both its textural as well as meditative qualities) the troupe has also enjoyed collaborations with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (Elgar’s The Apostles, 2018), Instruments of Time and Truth (Bach’s St Matthew Passion, 2017) and Oxford Baroque (Bach’s Mass in B minor, 2018). Previous tours include visits to Hong Kong and Singapore, France, Italy, Sweden, and the United States. The upcoming tour to the latter is the first the choir has undertaken since the start of the pandemic in early 2020.

With dates in Cambridge, New Haven, New York, and Princeton, the programme is an inspiring mix of new and old works by a range of celebrated composers, including William Byrd (1543-1623), Henry Purcell (1659-1695), Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986), Lionel Rogg (1936), Judith Weir (1954), and Nico Muhly (1981), among others. I spoke with Director of Music Benjamin Nicholas recently, and we discussed some timely topics: the choice of touring repertoire; what audiences might glean from the experiences of seeing, and being in, a choir; and what singing means in a post-(or whatever this is)-coronavirus world.

Photo (c) John Cairns

Your American tour is an interesting balance of contemporary and traditional works; why these works, and why include them on a tour?

Well, I think what we’re doing on tour is pretty typical of what we do most of the time. I do try and think about the concert programmes – the art of putting together a programme is a really exciting thing to do. It’s tough to get it right, and I’m aware we’re going to be singing in places that have great choral music already, and so I think it was a question of bringing something with us that might be unique in the sense that one piece is written specifically for us, other contemporary pieces are perhaps not performance so often – so I’m quite keen to put together a programme that contrasts the old with the new, which as I say is pretty typical of our repertoire.

During the university term we sing three services a week in the chapel at Merton and I would say that we include a lot of Renaissance music, obviously some romantic music, and 20th-21st century music, and so the tour programme is an extension of what we do in those services.

Do you program with themes in mind, or is it more instinctual, i.e. “I like how this sounds with that” ?

It’s a bit of both if I’m honest. I have gone for some contrasts, where we put two pieces next to each other. One of those pairings is the Byrd Motet “O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth” running straight into Judith Weir’s “Ave Regina caelorum” – one connection is simply that they are in the same key, so it makes for a very neat segue way, but also I think that it’s interesting that William Byrd wrote for Elizabeth I – he was indeed part of the Royal household – and Judith Weir is the current Master of the Queen’s Music, and obviously writes for the greater state occasions in the UK. So that was one thing, to put them together. The Judith Weir piece is also a bit of a personal piece, because it was written for us – it is particularly special. And then there’s the Purcell piece (“Jehova, quam multi sunt hostes mei”) moving directly into David Lang (“again”) – there’s no great link there, apart from the fact that I felt the contrast after the Purcell would be, hopefully, really arresting for the audience.

The act of communal singing, of this programme in particular, seems especially pregnant with symbolism. Singing was the first thing we lost in the pandemic.

That’s true.

What has the return been like for you and your members?

The very obvious practical change, when we came back to the university after the first lockdown, related to the basic guidance: yes we could sing, but only at a certain distance from one another. Merton Chapel is a good size and we were able to resume singing straight away, but all distanced. There’s no doubt that distancing honed everyone’s listening skills; everyone was so much more attuned, and they knew they had to have amazing antennae – the ears of an elephant – to hear everyone else, to make the performance whole. We did record a CD under those circumstances; it seems mad on one hand, but on the other I think all the work paid off. The choir has moved back together now, and are standing at a normal distance, but their listening skills have been enhanced by the distancing over the course of the pandemic. But whilst the pandemic is fresh in everyone’s minds and people missed being in university and missed touring and did miss singing three times a week in the chapel, I think people have got used to (the old routine) again very quickly; we’re basically back to normal and have been for about a year.

Now it’s been quite a striking difference at the BBC Proms concerts – what I found really staggering as an attendee is to hear all the great choral works in the Royal Albert Hall with hundreds of performers, because that didn’t come back last summer; it has taken much longer for that kind of music-making to resume. For all of us who’ve been at the Proms or heard things on the radio in the last couple weeks, things like Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony or The Dream Of Gerontius and so on, I think that’s been a very powerful reminder of what we lost. But I think when it comes to chamber music – and Merton Choir is, I suppose, the size of a chamber choir – I think we’ve now gotten used to being back together, and one of the great things of working with students is aht they move on pretty quickly. I think as far as they’re concerned we’ve been back to normal for some time, and normal is what they expect now. From my point of view I’ve used it as an opportunity to think about our repertoire a little bit. I hope it’s increasingly diverse, that it’s more interesting; I dropped some pieces which were not that great but which we did because they were in repertoire, so (this pandemic time) has been a chance to rebuild.

The pandemic time has many in classical thinking about that word “rebuild” – why organizations and artists do it ; how they do it; just who they are doing it for. This relates, I think, to the growing awareness around the need for diversity. What’s your feeling?

I completely agree. The interesting thing is that in terms of who we perform for back in the UK, our work is largely about enhancing the liturgy in medieval chapel, so that’s quite different from just being a concert-giving outfit. There are already these parameters in what we’re doing; the liturgy of the day dictates a lot of the music. So that means that there are certain texts that need to be sung and so on. Now, you then have a vast library of music from the last 500 years with the settings of those texts and so on and of course, a lot of the time we’re singing that music, however, we’ve always tried to commission new music at Merton, because it’s a choir of students, and part of the educational process is to introduce them to new music, some written by them or their peers, but other music is written by a cross-section of composers from all over the world. I’ve commissioned Nico Muhly in the US; Dobrinka Tabakova (1980), born in Bulgaria although she’s in London at the moment; Eriks Esenvalds (b. 1977), who is Latvian; Kerry Andrew (b. 1978) and Hannah Kendall (b. 1984); and obviously Judith Weir and James Macmillan (1959), both Scottish. The composers come from all over, because I want our repertoire to be as broad as it possibly can. Each of these composers brings a unique musical language and that enhances what we do in the chapel.

In terms of the membership of our choir, we want it to be as representative of the UK as possible, and, in terms of who we are singing for, I want audiences to come along, hear an English choir, and I just want them to experience something of what we do. So (on this tour) I’ve included two American composers, and that was because over the last few years we’ve explored a lot of contemporary composers – Libby Larsen (1950); Stephen Paulus (1949-2014) before he died; Glass (1937), Lang (1957), and Muhly. We recorded an album of American music just before the pandemic which we never had a chance to take to concerts. In a way this is a snapshot of the repertoire we sing, and you know, we hope audiences enjoy such varied kinds of music.

The Choir of Merton College, Oxford. Photo: Hugh Warwick

A choir seems like a symbol of community, reciprocity, support – things that went missing during the pandemic, and continue to be largely absent. What role do you see for choir membership in a post (or whatever this is) covid world?

The first thing to say is that the act of being in a choir brings people together. That whole thing whereby people have been separated – well, a choir immediately offers a reason for people to come together. Then there is the fact they have come together to make music; the active breathing in sync, the fact they’ve got to respond to one another in terms of pitch within an ensemble, these things make the connections between people all the stronger. So for the people who sing, getting back into a choir is a really important thing.

In this country we’ve found it’s been slow-going – yes, we’re lucky that at the university we’ve not been hugely impacted by that, but I’m aware a lot of the large choruses are down in numbers and it’s taken time for all these things to build back up. I do recognize it hasn’t just gone back straight away, and that people need to be reminded, particularly now, of the benefits of being in a choir and making music together.

It’s like the difference between playing team sports versuss things like skiing, tennis, or swimming; I was a pianist and sometime-band/orchestra member, but the experience of singing St. Matthew Passion in Berlin in 2018 was very much a thing apart from any individual experience. Singing is intimate, and singing with others, even more so.

It is exactly that. In terms of musical education I can understand there was a time when one of the conservatoires, the Royal College Of Music, insisted that first-year students be part of a chorus, and the students at the time didn’t understand why they had to do this, but it was, simply, all the skills one can take for granted are so enhanced and developed by being in a choir: pitch, rhythm, placing one’s voice, text, languages…

… awareness of others.

Yes, absolutely – the skills you might learn in general musicianship, you might do them in a class, but go into a choir and you are putting the repertoire study into real practice. So I can only think it’s a really good thing for all musicians to sing in a choir for a bit, and I would say in Merton College Choir we’re essentially a choir of 30 students, some of whom read music as their degree but many are scientists and lawyers and historians…

I love that kind of professional variety in your membership.

I love that too, and I love the fact plenty of people who will not be professional singers have wonderful musical skills regardless of their formal study routes. So we have good pianists, and good horn players singing with us, and as far as I’m concerned, as a director, you need all these ingredients. Yes, you need stellar voices, but you also need a lot of very good musicians, people who just want to enhance those musical skills they happen to have. You need those different elements to make a choir.

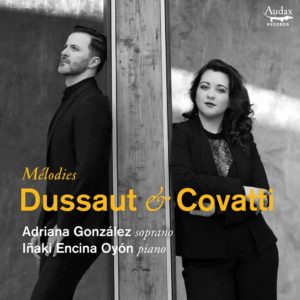

So what a treat it was, to come across the album

So what a treat it was, to come across the album  As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

Acknowledging the various roles Hensel fulfilled in life allows one to more fully engage in her art, and to contemplate the whys, wherefores, and hows inherent to her creative process. Thus might one build an understanding, of not only her body of works, but the uniquely creative elements at play within them. Elements of the past (Bach, Beethoven, Schubert), contemporaneous (Schumann, Liszt), and future (Brahms, Liszt) intermingle in some thoughtful ways, and one senses, especially in her later works, a through-compositional style that would’ve found fulsome expression on the opera stage, a medium for which she would have been eminently suited. Soprano Chen Reiss agrees on this point, and brings her own beguiling brand of elegant, operatic flair to a new album. Fanny Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder & Overtures (

Acknowledging the various roles Hensel fulfilled in life allows one to more fully engage in her art, and to contemplate the whys, wherefores, and hows inherent to her creative process. Thus might one build an understanding, of not only her body of works, but the uniquely creative elements at play within them. Elements of the past (Bach, Beethoven, Schubert), contemporaneous (Schumann, Liszt), and future (Brahms, Liszt) intermingle in some thoughtful ways, and one senses, especially in her later works, a through-compositional style that would’ve found fulsome expression on the opera stage, a medium for which she would have been eminently suited. Soprano Chen Reiss agrees on this point, and brings her own beguiling brand of elegant, operatic flair to a new album. Fanny Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder & Overtures (

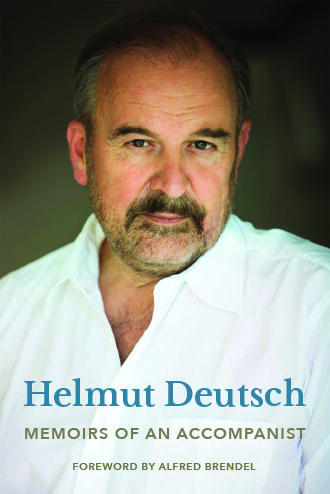

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.